Difference between revisions of "2021 AIME II Problems/Problem 5"

MRENTHUSIASM (talk | contribs) m (→Solution 2 (Casework: Detailed Explanation of Solution 1)) |

Sblnuclear17 (talk | contribs) m (→Solution 2 (Inequalities and Casework)) |

||

| (78 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

==Solution 1== | ==Solution 1== | ||

| − | We start by defining a triangle. The two small sides MUST add to a larger sum than the long side. We are given 4 and 10 as the sides, so we know that the | + | We start by defining a triangle. The two small sides MUST add to a larger sum than the long side. We are given <math>4</math> and <math>10</math> as the sides, so we know that the <math>3</math>rd side is between <math>6</math> and <math>14</math>, exclusive. We also have to consider the word OBTUSE triangles. That means that the two small sides squared is less than the <math>3</math>rd side. So the triangles' sides are between <math>6</math> and <math>\sqrt{84}</math> exclusive, and the larger bound is between <math>\sqrt{116}</math> and <math>14</math>, exclusive. The area of these triangles are from <math>0</math> (straight line) to <math>2\sqrt{84}</math> on the first "small bound" and the larger bound is between <math>0</math> and <math>20</math>. |

| − | <math>0 < s < 2\sqrt{84}</math> is our first equation, and <math>0 < s < 20</math> is our | + | <math>0 < s < 2\sqrt{84}</math> is our first equation, and <math>0 < s < 20</math> is our <math>2</math>nd equation. Therefore, the area is between <math>\sqrt{336}</math> and <math>\sqrt{400}</math>, so our final answer is <math>\boxed{736}</math>. |

~ARCTICTURN | ~ARCTICTURN | ||

| − | ==Solution 2 (Casework | + | ==Solution 2 (Inequalities and Casework)== |

| − | + | If <math>a,b,</math> and <math>c</math> are the side-lengths of an obtuse triangle with <math>a\leq b\leq c,</math> then both of the following must be satisfied: | |

| − | * < | + | * <i>Triangle Inequality Theorem:</i> <math>a+b>c</math> |

| − | * < | + | * <i>Pythagorean Inequality Theorem:</i> <math>a^2+b^2<c^2</math> |

| − | <b> | + | For one such obtuse triangle, let <math>4,10,</math> and <math>x</math> be its side-lengths and <math>K</math> be its area. We apply casework to its longest side: |

| + | |||

| + | <b>Case (1): The longest side has length <math>\boldsymbol{10,}</math> so <math>\boldsymbol{0<x<10.}</math></b> | ||

| + | |||

| + | By the Triangle Inequality Theorem, we have <math>4+x>10,</math> from which <math>x>6.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | By the Pythagorean Inequality Theorem, we have <math>4^2+x^2<10^2,</math> from which <math>x<\sqrt{84}.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Taking the intersection produces <math>6<x<\sqrt{84}</math> for this case. | ||

| + | |||

| + | At <math>x=6,</math> the obtuse triangle degenerates into a straight line with area <math>K=0;</math> at <math>x=\sqrt{84},</math> the obtuse triangle degenerates into a right triangle with area <math>K=\frac12\cdot4\cdot\sqrt{84}=2\sqrt{84}.</math> Together, we obtain <math>0<K<2\sqrt{84},</math> or <math>K\in\left(0,2\sqrt{84}\right).</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <b>Case (2): The longest side has length <math>\boldsymbol{x,}</math> so <math>\boldsymbol{x\geq10.}</math></b> | ||

| + | |||

| + | By the Triangle Inequality Theorem, we have <math>4+10>x,</math> from which <math>x<14.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | By the Pythagorean Inequality Theorem, we have <math>4^2+10^2<x^2,</math> from which <math>x>\sqrt{116}.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Taking the intersection produces <math>\sqrt{116}<x<14</math> for this case. | ||

| + | |||

| + | At <math>x=14,</math> the obtuse triangle degenerates into a straight line with area <math>K=0;</math> at <math>x=\sqrt{116},</math> the obtuse triangle degenerates into a right triangle with area <math>K=\frac12\cdot4\cdot10=20.</math> Together, we obtain <math>0<K<20,</math> or <math>K\in\left(0,20\right).</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <b>Answer</b> | ||

| + | |||

| + | It is possible for noncongruent obtuse triangles to have the same area. Therefore, all such positive real numbers <math>s</math> are in exactly one of <math>\left(0,2\sqrt{84}\right)</math> or <math>\left(0,20\right).</math> By the exclusive disjunction, the set of all such <math>s</math> is <cmath>[a,b)=\left(0,2\sqrt{84}\right)\oplus\left(0,20\right)=\left[2\sqrt{84},20\right),</cmath> from which <math>a^2+b^2=\boxed{736}.</math> | ||

~MRENTHUSIASM | ~MRENTHUSIASM | ||

| − | ==See | + | ==Solution 3== |

| + | |||

| + | We have the diagram below. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <asy> | ||

| + | |||

| + | draw((0,0)--(1,2*sqrt(3))); | ||

| + | draw((1,2*sqrt(3))--(10,0)); | ||

| + | draw((10,0)--(0,0)); | ||

| + | label("$A$",(0,0),SW); | ||

| + | label("$B$",(1,2*sqrt(3)),N); | ||

| + | label("$C$",(10,0),SE); | ||

| + | label("$\theta$",(0,0),NE); | ||

| + | label("$\alpha$",(1,2*sqrt(3)),SSE); | ||

| + | label("$4$",(0,0)--(1,2*sqrt(3)),WNW); | ||

| + | label("$10$",(0,0)--(10,0),S); | ||

| + | |||

| + | </asy> | ||

| + | |||

| + | We proceed by taking cases on the angles that can be obtuse, and finding the ranges for <math>s</math> that they yield . | ||

| + | |||

| + | If angle <math>\theta</math> is obtuse, then we have that <math>s \in (0,20)</math>. This is because <math>s=20</math> is attained at <math>\theta = 90^{\circ}</math>, and the area of the triangle is strictly decreasing as <math>\theta</math> increases beyond <math>90^{\circ}</math>. This can be observed from | ||

| + | <cmath>s=\frac{1}{2}(4)(10)\sin\theta</cmath>by noting that <math>\sin\theta</math> is decreasing in <math>\theta \in (90^{\circ},180^{\circ})</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Then, we note that if <math>\alpha</math> is obtuse, we have <math>s \in (0,4\sqrt{21})</math>. This is because we get <math>x=\sqrt{10^2-4^2}=\sqrt{84}=2\sqrt{21}</math> when <math>\alpha=90^{\circ}</math>, yileding <math>s=4\sqrt{21}</math>. Then, <math>s</math> is decreasing as <math>\alpha</math> increases by the same argument as before. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>\angle{ACB}</math> cannot be obtuse since <math>AC>AB</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Now we have the intervals <math>s \in (0,20)</math> and <math>s \in (0,4\sqrt{21})</math> for the cases where <math>\theta</math> and <math>\alpha</math> are obtuse, respectively. We are looking for the <math>s</math> that are in exactly one of these intervals, and because <math>4\sqrt{21}<20</math>, the desired range is | ||

| + | <cmath>s\in [4\sqrt{21},20)</cmath>giving <cmath>a^2+b^2=\boxed{736}\Box</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 4== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Note: Archimedes15 Solution which I added an answer | ||

| + | here are two cases. Either the <math>4</math> and <math>10</math> are around an obtuse angle or the <math>4</math> and <math>10</math> are around an acute triangle. If they are around the obtuse angle, the area of that triangle is <math><20</math> as we have <math>\frac{1}{2} \cdot 40 \cdot \sin{\alpha}</math> and <math>\sin</math> is at most <math>1</math>. Note that for the other case, the side lengths around the obtuse angle must be <math>4</math> and <math>x</math> where we have <math>16+x^2 < 100 \rightarrow x < 2\sqrt{21}</math>. Using the same logic as the other case, the area is at most <math>4\sqrt{21}</math>. Square and add <math>4\sqrt{21}</math> and <math>20</math> to get the right answer <cmath>a^2+b^2= \boxed{736}\Box</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 5 (Circles)== | ||

| + | For <math>\triangle ABC,</math> we fix <math>AB=10</math> and <math>BC=4.</math> Without the loss of generality, we consider <math>C</math> on only one side of <math>\overline{AB}.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | As shown below, all locations for <math>C</math> at which <math>\triangle ABC</math> is an obtuse triangle are indicated in red, excluding the endpoints. | ||

| + | <asy> | ||

| + | /* Made by MRENTHUSIASM */ | ||

| + | size(300); | ||

| + | pair A, B, O, P, Q, C1, C2, D; | ||

| + | A = origin; | ||

| + | B = (10,0); | ||

| + | O = midpoint(A--B); | ||

| + | P = B - (4,0); | ||

| + | Q = B + (4,0); | ||

| + | C1 = intersectionpoints(D--D+(100,0),Arc(B,Q,P))[1]; | ||

| + | C2 = B + (0,4); | ||

| + | D = intersectionpoint(Arc(O,B,A),Arc(B,Q,P)); | ||

| + | |||

| + | draw(Arc(O,B,A)^^Arc(B,C2,D)^^A--Q); | ||

| + | draw(Arc(B,Q,C2)^^Arc(B,D,P),red); | ||

| + | |||

| + | dot("$A$", A, 1.5*S, linewidth(4.5)); | ||

| + | dot("$B$", B, 1.5*S, linewidth(4.5)); | ||

| + | dot(O, linewidth(4.5)); | ||

| + | dot(P^^C2^^D^^Q, linewidth(0.8), UnFill); | ||

| + | |||

| + | Label L1 = Label("$10$", align=(0,0), position=MidPoint, filltype=Fill(3,0,white)); | ||

| + | Label L2 = Label("$4$", align=(0,0), position=MidPoint, filltype=Fill(3,0,white)); | ||

| + | draw(A-(0,2)--B-(0,2), L=L1, arrow=Arrows(),bar=Bars(15)); | ||

| + | draw(B-(0,2)--Q-(0,2), L=L2, arrow=Arrows(),bar=Bars(15)); | ||

| + | |||

| + | label("$\angle C$ obtuse",(midpoint(Arc(B,D,P)).x,2),2.5*W,red); | ||

| + | label("$\angle B$ obtuse",(midpoint(Arc(B,Q,C2)).x,2),5*E,red); | ||

| + | </asy> | ||

| + | Note that: | ||

| + | <ol style="margin-left: 1.5em;"> | ||

| + | <li>The region in which <math>\angle B</math> is obtuse is determined by construction.</li><p> | ||

| + | <li>The region in which <math>\angle C</math> is obtuse is determined by the corollaries of the Inscribed Angle Theorem.</li><p> | ||

| + | </ol> | ||

| + | For any fixed value of <math>s,</math> the height from <math>C</math> is fixed. We need obtuse <math>\triangle ABC</math> to be unique, so there can only be one possible location for <math>C.</math> As shown below, all possible locations for <math>C</math> are on minor arc <math>\widehat{C_1C_2},</math> including <math>C_1</math> but excluding <math>C_2.</math> | ||

| + | <asy> | ||

| + | /* Made by MRENTHUSIASM */ | ||

| + | size(250); | ||

| + | pair A, B, O, P, Q, C1, C2, D; | ||

| + | A = origin; | ||

| + | B = (10,0); | ||

| + | O = midpoint(A--B); | ||

| + | P = B - (4,0); | ||

| + | Q = B + (4,0); | ||

| + | C2 = B + (0,4); | ||

| + | D = intersectionpoint(Arc(O,B,A),Arc(B,Q,P)); | ||

| + | C1 = intersectionpoint(D--D+(100,0),Arc(B,Q,C2)); | ||

| + | |||

| + | draw(Arc(O,B,A)^^Arc(B,C2,D)^^A--Q); | ||

| + | draw(Arc(B,Q,C1)^^Arc(B,D,P),red); | ||

| + | draw(Arc(B,C1,C2),green); | ||

| + | draw((A.x,D.y)--(Q.x,D.y),dashed); | ||

| + | |||

| + | dot("$A$", A, 1.5*S, linewidth(4.5)); | ||

| + | dot("$B$", B, 1.5*S, linewidth(4.5)); | ||

| + | dot("$D$", D, 1.5*dir(75), linewidth(0.8), UnFill); | ||

| + | dot("$C_2$", C2, 1.5*N, linewidth(4.5)); | ||

| + | dot("$C_1$", C1, 1.5*dir(C1-B), linewidth(4.5)); | ||

| + | dot(O, linewidth(4.5)); | ||

| + | dot(P^^C2^^Q, linewidth(0.8), UnFill); | ||

| + | dot(C1, green+linewidth(4.5)); | ||

| + | |||

| + | Label L1 = Label("$10$", align=(0,0), position=MidPoint, filltype=Fill(3,0,white)); | ||

| + | Label L2 = Label("$4$", align=(0,0), position=MidPoint, filltype=Fill(3,0,white)); | ||

| + | draw(A-(0,2)--B-(0,2), L=L1, arrow=Arrows(),bar=Bars(15)); | ||

| + | draw(B-(0,2)--Q-(0,2), L=L2, arrow=Arrows(),bar=Bars(15)); | ||

| + | </asy> | ||

| + | Let the brackets denote areas: | ||

| + | <ul style="list-style-type:square;"> | ||

| + | <li>If <math>C=C_1,</math> then <math>[ABC]</math> will be minimized (attainable). By the same base and height and the Inscribed Angle Theorem, we have | ||

| + | <cmath>\begin{align*} | ||

| + | [ABC]&=[ABD] \\ | ||

| + | &=\frac12\cdot BD\cdot DA \\ | ||

| + | &=\frac12\cdot BD\cdot \sqrt{AB^2-BD^2} \\ | ||

| + | &=\frac12\cdot 4\cdot \sqrt{10^2-4^2} \\ | ||

| + | &=2\sqrt{84}. | ||

| + | \end{align*}</cmath></li><p> | ||

| + | <li>If <math>C=C_2,</math> then <math>[ABC]</math> will be maximized (unattainable). For this right triangle, we have | ||

| + | <cmath>\begin{align*} | ||

| + | [ABC]&=\frac12\cdot AB\cdot BC \\ | ||

| + | &=\frac12\cdot 10\cdot 4 \\ | ||

| + | &=20. | ||

| + | \end{align*}</cmath></li><p> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | Finally, the set of all such <math>s</math> is <math>[a,b)=\left[2\sqrt{84},20\right),</math> from which <math>a^2+b^2=\boxed{736}.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ~MRENTHUSIASM (credit given to Snowfan) | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Solution 6 == | ||

| + | Let a triangle in <math>\tau(s)</math> be <math>ABC</math>, where <math>AB = 4</math> and <math>BC = 10</math>. We will proceed with two cases: | ||

| + | |||

| + | Case 1: <math>\angle ABC</math> is obtuse. If <math>\angle ABC</math> is obtuse, then, if we imagine <math>AB</math> as the base of our triangle, the height can be anything in the range <math>(0,10)</math>; therefore, the area of the triangle will fall in the range of <math>(0, 20)</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Case 2: <math>\angle BAC</math> is obtuse. Then, if we imagine <math>AB</math> as the base of our triangle, the height can be anything in the range <math>\left(0, \sqrt{10^{2} - 4^{2}}\right)</math>. Therefore, the area of the triangle will fall in the range of <math>\left(0, 2 \sqrt{84}\right)</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | If <math>s < 2 \sqrt{84}</math>, there will exist two types of triangles in <math>\tau(s)</math> - one type with <math>\angle ABC</math> obtuse; the other type with <math>\angle BAC</math> obtuse. If <math>s \geq 2 \sqrt{84}</math>, as we just found, <math>\angle BAC</math> cannot be obtuse, so therefore, there is only one type of triangle - the one in which <math>\angle ABC</math> is obtuse. Also, if <math>s > 20</math>, no triangle exists with lengths <math>4</math> and <math>10</math>. Therefore, <math>s</math> is in the range <math>\left[ 2 \sqrt{84}, 20\right)</math>, so our answer is <math>\left(2 \sqrt{84}\right)^{2} + 20^{2} = \boxed{736}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Alternatively, refer to Solution 5 for the geometric interpretation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ~ihatemath123 | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Solution 7 == | ||

| + | [[File:2021 AIME II 5.png|400px|right]] | ||

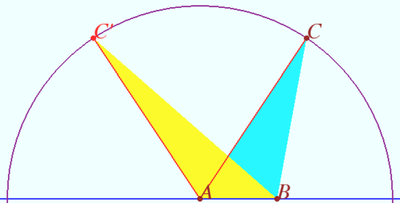

| + | Let's rephrase the condition. It is required to find such values of the area of an obtuse triangle with sides <math>4</math> and <math>10,</math> when there is exactly one such obtuse triangle. In the diagram, <math>AB = 4, AC = 10.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The largest area of triangle with sides <math>4</math> and <math>10</math> is <math>20</math> for a right triangle with legs <math>4</math> and <math>10</math> (<math>AC\perp AB</math>). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The diagram shows triangles with equal heights. The yellow triangle <math>ABC'</math> has the longest side <math>BC',</math> the blue triangle <math>ABC</math> has the longest side <math>AC.</math> | ||

| + | If <math>BC\perp AB,</math> then<math> BC = \sqrt {AC^2 – AB^2} = 2 \sqrt{21}</math> the area is equal to <math>4\sqrt{21}.</math> In the interval, the blue triangle <math>ABC</math> is acute-angled, the yellow triangle <math>ABC'</math> is obtuse-angled. Their heights and areas are equal. The condition is met. | ||

| + | |||

| + | If the area is less than <math>4\sqrt{21},</math> both triangles are obtuse, not equal, so the condition is not met. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Therefore, <math>s</math> is in the range <math>\left[ 4 \sqrt{21}, 20\right)</math>, so answer is <math>\left(4 \sqrt{21}\right)^{2} + 20^{2} = \boxed{736}</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''vladimir.shelomovskii@gmail.com, vvsss''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 8== | ||

| + | If <math>4</math> and <math>10</math> are the shortest sides and <math>\angle C</math> is the included angle, then the area is <cmath>\frac{4\cdot10\cdot\sin\angle C}{2} = 20\sin\angle C.</cmath> | ||

| + | Because <math>0\leq\sin\angle C\leq1</math>, the maximum value of <math>20\sin\angle C</math> is <math>20</math>, so <math>s\leq20</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | If <math>4</math> is a shortest side and <math>10</math> is the longest side, the length of the other short side is <math>4\cos\angle C+2\sqrt{4\cos^2 \angle C+21}</math> by law of cosines, and the area is <math>2\left(4\cos\angle C+2\sqrt{4\cos^2\angle C+21}\right)\sqrt{1-\cos\angle C}</math>. Because <math>-1\le \cos\angle C\le 0</math>, this is minimized if <math>\cos\angle C=0</math>, where <math>s=4\sqrt{21}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | So, the answer is <math>20^2+\left(4\sqrt{21}\right)^2=\boxed{736}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ~ryanbear | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Video Solution by Interstigation== | ||

| + | https://youtu.be/ODokTEt3EVA | ||

| + | |||

| + | ~Interstigation | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==See Also== | ||

{{AIME box|year=2021|n=II|num-b=4|num-a=6}} | {{AIME box|year=2021|n=II|num-b=4|num-a=6}} | ||

{{MAA Notice}} | {{MAA Notice}} | ||

Latest revision as of 23:43, 1 January 2023

Contents

Problem

For positive real numbers ![]() , let

, let ![]() denote the set of all obtuse triangles that have area

denote the set of all obtuse triangles that have area ![]() and two sides with lengths

and two sides with lengths ![]() and

and ![]() . The set of all

. The set of all ![]() for which

for which ![]() is nonempty, but all triangles in

is nonempty, but all triangles in ![]() are congruent, is an interval

are congruent, is an interval ![]() . Find

. Find ![]() .

.

Solution 1

We start by defining a triangle. The two small sides MUST add to a larger sum than the long side. We are given ![]() and

and ![]() as the sides, so we know that the

as the sides, so we know that the ![]() rd side is between

rd side is between ![]() and

and ![]() , exclusive. We also have to consider the word OBTUSE triangles. That means that the two small sides squared is less than the

, exclusive. We also have to consider the word OBTUSE triangles. That means that the two small sides squared is less than the ![]() rd side. So the triangles' sides are between

rd side. So the triangles' sides are between ![]() and

and ![]() exclusive, and the larger bound is between

exclusive, and the larger bound is between ![]() and

and ![]() , exclusive. The area of these triangles are from

, exclusive. The area of these triangles are from ![]() (straight line) to

(straight line) to ![]() on the first "small bound" and the larger bound is between

on the first "small bound" and the larger bound is between ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

![]() is our first equation, and

is our first equation, and ![]() is our

is our ![]() nd equation. Therefore, the area is between

nd equation. Therefore, the area is between ![]() and

and ![]() , so our final answer is

, so our final answer is ![]() .

.

~ARCTICTURN

Solution 2 (Inequalities and Casework)

If ![]() and

and ![]() are the side-lengths of an obtuse triangle with

are the side-lengths of an obtuse triangle with ![]() then both of the following must be satisfied:

then both of the following must be satisfied:

- Triangle Inequality Theorem:

- Pythagorean Inequality Theorem:

For one such obtuse triangle, let ![]() and

and ![]() be its side-lengths and

be its side-lengths and ![]() be its area. We apply casework to its longest side:

be its area. We apply casework to its longest side:

Case (1): The longest side has length ![]() so

so ![]()

By the Triangle Inequality Theorem, we have ![]() from which

from which ![]()

By the Pythagorean Inequality Theorem, we have ![]() from which

from which ![]()

Taking the intersection produces ![]() for this case.

for this case.

At ![]() the obtuse triangle degenerates into a straight line with area

the obtuse triangle degenerates into a straight line with area ![]() at

at ![]() the obtuse triangle degenerates into a right triangle with area

the obtuse triangle degenerates into a right triangle with area ![]() Together, we obtain

Together, we obtain ![]() or

or ![]()

Case (2): The longest side has length ![]() so

so ![]()

By the Triangle Inequality Theorem, we have ![]() from which

from which ![]()

By the Pythagorean Inequality Theorem, we have ![]() from which

from which ![]()

Taking the intersection produces ![]() for this case.

for this case.

At ![]() the obtuse triangle degenerates into a straight line with area

the obtuse triangle degenerates into a straight line with area ![]() at

at ![]() the obtuse triangle degenerates into a right triangle with area

the obtuse triangle degenerates into a right triangle with area ![]() Together, we obtain

Together, we obtain ![]() or

or ![]()

Answer

It is possible for noncongruent obtuse triangles to have the same area. Therefore, all such positive real numbers ![]() are in exactly one of

are in exactly one of ![]() or

or ![]() By the exclusive disjunction, the set of all such

By the exclusive disjunction, the set of all such ![]() is

is ![]() from which

from which ![]()

~MRENTHUSIASM

Solution 3

We have the diagram below.

![[asy] draw((0,0)--(1,2*sqrt(3))); draw((1,2*sqrt(3))--(10,0)); draw((10,0)--(0,0)); label("$A$",(0,0),SW); label("$B$",(1,2*sqrt(3)),N); label("$C$",(10,0),SE); label("$\theta$",(0,0),NE); label("$\alpha$",(1,2*sqrt(3)),SSE); label("$4$",(0,0)--(1,2*sqrt(3)),WNW); label("$10$",(0,0)--(10,0),S); [/asy]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/6/9/4/6940b758ab02beb075b54be2d68de6be1ceb38ec.png)

We proceed by taking cases on the angles that can be obtuse, and finding the ranges for ![]() that they yield .

that they yield .

If angle ![]() is obtuse, then we have that

is obtuse, then we have that ![]() . This is because

. This is because ![]() is attained at

is attained at ![]() , and the area of the triangle is strictly decreasing as

, and the area of the triangle is strictly decreasing as ![]() increases beyond

increases beyond ![]() . This can be observed from

. This can be observed from

![]() by noting that

by noting that ![]() is decreasing in

is decreasing in ![]() .

.

Then, we note that if ![]() is obtuse, we have

is obtuse, we have ![]() . This is because we get

. This is because we get ![]() when

when ![]() , yileding

, yileding ![]() . Then,

. Then, ![]() is decreasing as

is decreasing as ![]() increases by the same argument as before.

increases by the same argument as before.

![]() cannot be obtuse since

cannot be obtuse since ![]() .

.

Now we have the intervals ![]() and

and ![]() for the cases where

for the cases where ![]() and

and ![]() are obtuse, respectively. We are looking for the

are obtuse, respectively. We are looking for the ![]() that are in exactly one of these intervals, and because

that are in exactly one of these intervals, and because ![]() , the desired range is

, the desired range is

![]() giving

giving ![]()

Solution 4

Note: Archimedes15 Solution which I added an answer

here are two cases. Either the ![]() and

and ![]() are around an obtuse angle or the

are around an obtuse angle or the ![]() and

and ![]() are around an acute triangle. If they are around the obtuse angle, the area of that triangle is

are around an acute triangle. If they are around the obtuse angle, the area of that triangle is ![]() as we have

as we have ![]() and

and ![]() is at most

is at most ![]() . Note that for the other case, the side lengths around the obtuse angle must be

. Note that for the other case, the side lengths around the obtuse angle must be ![]() and

and ![]() where we have

where we have ![]() . Using the same logic as the other case, the area is at most

. Using the same logic as the other case, the area is at most ![]() . Square and add

. Square and add ![]() and

and ![]() to get the right answer

to get the right answer ![]()

Solution 5 (Circles)

For ![]() we fix

we fix ![]() and

and ![]() Without the loss of generality, we consider

Without the loss of generality, we consider ![]() on only one side of

on only one side of ![]()

As shown below, all locations for ![]() at which

at which ![]() is an obtuse triangle are indicated in red, excluding the endpoints.

is an obtuse triangle are indicated in red, excluding the endpoints.

![[asy] /* Made by MRENTHUSIASM */ size(300); pair A, B, O, P, Q, C1, C2, D; A = origin; B = (10,0); O = midpoint(A--B); P = B - (4,0); Q = B + (4,0); C1 = intersectionpoints(D--D+(100,0),Arc(B,Q,P))[1]; C2 = B + (0,4); D = intersectionpoint(Arc(O,B,A),Arc(B,Q,P)); draw(Arc(O,B,A)^^Arc(B,C2,D)^^A--Q); draw(Arc(B,Q,C2)^^Arc(B,D,P),red); dot("$A$", A, 1.5*S, linewidth(4.5)); dot("$B$", B, 1.5*S, linewidth(4.5)); dot(O, linewidth(4.5)); dot(P^^C2^^D^^Q, linewidth(0.8), UnFill); Label L1 = Label("$10$", align=(0,0), position=MidPoint, filltype=Fill(3,0,white)); Label L2 = Label("$4$", align=(0,0), position=MidPoint, filltype=Fill(3,0,white)); draw(A-(0,2)--B-(0,2), L=L1, arrow=Arrows(),bar=Bars(15)); draw(B-(0,2)--Q-(0,2), L=L2, arrow=Arrows(),bar=Bars(15)); label("$\angle C$ obtuse",(midpoint(Arc(B,D,P)).x,2),2.5*W,red); label("$\angle B$ obtuse",(midpoint(Arc(B,Q,C2)).x,2),5*E,red); [/asy]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/1/8/e/18e2bd9cca76db19a046b9e4a1594f5a5d3a91d2.png) Note that:

Note that:

- The region in which

is obtuse is determined by construction.

is obtuse is determined by construction. - The region in which

is obtuse is determined by the corollaries of the Inscribed Angle Theorem.

is obtuse is determined by the corollaries of the Inscribed Angle Theorem.

For any fixed value of ![]() the height from

the height from ![]() is fixed. We need obtuse

is fixed. We need obtuse ![]() to be unique, so there can only be one possible location for

to be unique, so there can only be one possible location for ![]() As shown below, all possible locations for

As shown below, all possible locations for ![]() are on minor arc

are on minor arc ![]() including

including ![]() but excluding

but excluding ![]()

![[asy] /* Made by MRENTHUSIASM */ size(250); pair A, B, O, P, Q, C1, C2, D; A = origin; B = (10,0); O = midpoint(A--B); P = B - (4,0); Q = B + (4,0); C2 = B + (0,4); D = intersectionpoint(Arc(O,B,A),Arc(B,Q,P)); C1 = intersectionpoint(D--D+(100,0),Arc(B,Q,C2)); draw(Arc(O,B,A)^^Arc(B,C2,D)^^A--Q); draw(Arc(B,Q,C1)^^Arc(B,D,P),red); draw(Arc(B,C1,C2),green); draw((A.x,D.y)--(Q.x,D.y),dashed); dot("$A$", A, 1.5*S, linewidth(4.5)); dot("$B$", B, 1.5*S, linewidth(4.5)); dot("$D$", D, 1.5*dir(75), linewidth(0.8), UnFill); dot("$C_2$", C2, 1.5*N, linewidth(4.5)); dot("$C_1$", C1, 1.5*dir(C1-B), linewidth(4.5)); dot(O, linewidth(4.5)); dot(P^^C2^^Q, linewidth(0.8), UnFill); dot(C1, green+linewidth(4.5)); Label L1 = Label("$10$", align=(0,0), position=MidPoint, filltype=Fill(3,0,white)); Label L2 = Label("$4$", align=(0,0), position=MidPoint, filltype=Fill(3,0,white)); draw(A-(0,2)--B-(0,2), L=L1, arrow=Arrows(),bar=Bars(15)); draw(B-(0,2)--Q-(0,2), L=L2, arrow=Arrows(),bar=Bars(15)); [/asy]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/d/5/8/d5866dc17da756aa17b80a18837c21dd1555de0c.png) Let the brackets denote areas:

Let the brackets denote areas:

- If

then

then ![$[ABC]$](//latex.artofproblemsolving.com/d/3/3/d33cc80fa8f093e155c5be46d2e5d9da3d7e1ef5.png) will be minimized (attainable). By the same base and height and the Inscribed Angle Theorem, we have

will be minimized (attainable). By the same base and height and the Inscribed Angle Theorem, we have

![\begin{align*} [ABC]&=[ABD] \\ &=\frac12\cdot BD\cdot DA \\ &=\frac12\cdot BD\cdot \sqrt{AB^2-BD^2} \\ &=\frac12\cdot 4\cdot \sqrt{10^2-4^2} \\ &=2\sqrt{84}. \end{align*}](//latex.artofproblemsolving.com/9/2/7/927b1f1b76a8b725a60b4b3904816b98df28d33d.png)

- If

then

then ![$[ABC]$](//latex.artofproblemsolving.com/d/3/3/d33cc80fa8f093e155c5be46d2e5d9da3d7e1ef5.png) will be maximized (unattainable). For this right triangle, we have

will be maximized (unattainable). For this right triangle, we have

![\begin{align*} [ABC]&=\frac12\cdot AB\cdot BC \\ &=\frac12\cdot 10\cdot 4 \\ &=20. \end{align*}](//latex.artofproblemsolving.com/e/0/f/e0f25498d2303979005c472c701f20525459cdaa.png)

Finally, the set of all such ![]() is

is ![]() from which

from which ![]()

~MRENTHUSIASM (credit given to Snowfan)

Solution 6

Let a triangle in ![]() be

be ![]() , where

, where ![]() and

and ![]() . We will proceed with two cases:

. We will proceed with two cases:

Case 1: ![]() is obtuse. If

is obtuse. If ![]() is obtuse, then, if we imagine

is obtuse, then, if we imagine ![]() as the base of our triangle, the height can be anything in the range

as the base of our triangle, the height can be anything in the range ![]() ; therefore, the area of the triangle will fall in the range of

; therefore, the area of the triangle will fall in the range of ![]() .

.

Case 2: ![]() is obtuse. Then, if we imagine

is obtuse. Then, if we imagine ![]() as the base of our triangle, the height can be anything in the range

as the base of our triangle, the height can be anything in the range ![]() . Therefore, the area of the triangle will fall in the range of

. Therefore, the area of the triangle will fall in the range of ![]() .

.

If ![]() , there will exist two types of triangles in

, there will exist two types of triangles in ![]() - one type with

- one type with ![]() obtuse; the other type with

obtuse; the other type with ![]() obtuse. If

obtuse. If ![]() , as we just found,

, as we just found, ![]() cannot be obtuse, so therefore, there is only one type of triangle - the one in which

cannot be obtuse, so therefore, there is only one type of triangle - the one in which ![]() is obtuse. Also, if

is obtuse. Also, if ![]() , no triangle exists with lengths

, no triangle exists with lengths ![]() and

and ![]() . Therefore,

. Therefore, ![]() is in the range

is in the range ![]() , so our answer is

, so our answer is ![]() .

.

Alternatively, refer to Solution 5 for the geometric interpretation.

~ihatemath123

Solution 7

Let's rephrase the condition. It is required to find such values of the area of an obtuse triangle with sides ![]() and

and ![]() when there is exactly one such obtuse triangle. In the diagram,

when there is exactly one such obtuse triangle. In the diagram, ![]()

The largest area of triangle with sides ![]() and

and ![]() is

is ![]() for a right triangle with legs

for a right triangle with legs ![]() and

and ![]() (

(![]() ).

).

The diagram shows triangles with equal heights. The yellow triangle ![]() has the longest side

has the longest side ![]() the blue triangle

the blue triangle ![]() has the longest side

has the longest side ![]() If

If ![]() then

then![]() the area is equal to

the area is equal to ![]() In the interval, the blue triangle

In the interval, the blue triangle ![]() is acute-angled, the yellow triangle

is acute-angled, the yellow triangle ![]() is obtuse-angled. Their heights and areas are equal. The condition is met.

is obtuse-angled. Their heights and areas are equal. The condition is met.

If the area is less than ![]() both triangles are obtuse, not equal, so the condition is not met.

both triangles are obtuse, not equal, so the condition is not met.

Therefore, ![]() is in the range

is in the range ![]() , so answer is

, so answer is ![]()

vladimir.shelomovskii@gmail.com, vvsss

Solution 8

If ![]() and

and ![]() are the shortest sides and

are the shortest sides and ![]() is the included angle, then the area is

is the included angle, then the area is ![]() Because

Because ![]() , the maximum value of

, the maximum value of ![]() is

is ![]() , so

, so ![]() .

.

If ![]() is a shortest side and

is a shortest side and ![]() is the longest side, the length of the other short side is

is the longest side, the length of the other short side is ![]() by law of cosines, and the area is

by law of cosines, and the area is ![]() . Because

. Because ![]() , this is minimized if

, this is minimized if ![]() , where

, where ![]() .

.

So, the answer is ![]() .

.

~ryanbear

Video Solution by Interstigation

~Interstigation

See Also

| 2021 AIME II (Problems • Answer Key • Resources) | ||

| Preceded by Problem 4 |

Followed by Problem 6 | |

| 1 • 2 • 3 • 4 • 5 • 6 • 7 • 8 • 9 • 10 • 11 • 12 • 13 • 14 • 15 | ||

| All AIME Problems and Solutions | ||

The problems on this page are copyrighted by the Mathematical Association of America's American Mathematics Competitions.

![\begin{align*} [ABC]&=[ABD] \\ &=\frac12\cdot BD\cdot DA \\ &=\frac12\cdot BD\cdot \sqrt{AB^2-BD^2} \\ &=\frac12\cdot 4\cdot \sqrt{10^2-4^2} \\ &=2\sqrt{84}. \end{align*}](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/9/2/7/927b1f1b76a8b725a60b4b3904816b98df28d33d.png)

![\begin{align*} [ABC]&=\frac12\cdot AB\cdot BC \\ &=\frac12\cdot 10\cdot 4 \\ &=20. \end{align*}](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/e/0/f/e0f25498d2303979005c472c701f20525459cdaa.png)