Difference between revisions of "Radical axis"

(→Proofs) |

|||

| (32 intermediate revisions by 15 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

==Introduction== | ==Introduction== | ||

The theory of radical axis is a priceless geometric tool that can solve formidable geometric problems fairly readily. Problems involving it can be found on many major math olympiad competitions, including the prestigious [[USAMO]]. Therefore, any aspiring math olympian should peruse this material carefully, as it may contain the keys to one's future success. | The theory of radical axis is a priceless geometric tool that can solve formidable geometric problems fairly readily. Problems involving it can be found on many major math olympiad competitions, including the prestigious [[USAMO]]. Therefore, any aspiring math olympian should peruse this material carefully, as it may contain the keys to one's future success. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Not all theorems will be fully proven in this text. The objective of this document is to introduce you to some key concepts, and then give you a chance to derive some of the beautiful results on your own. In that way, you will understand and retain the information in here much more solidly. Finally, your newfound knowledge will be tested on a few challenging problems that are exemplary examples on how radical axis theory can be used and why it pertains to that situation. I hope after you read this text, you will become a better math student, armed with another tool to solve difficult problems. But, anyway, good luck. | ||

| + | |||

==Definitions== | ==Definitions== | ||

| − | The '''power''' of point <math> | + | The '''power''' of point <math>P</math> with respect to circle <math>\omega</math> (with radius <math>r</math> and center <math>O</math>), which shall thereafter be dubbed <math>pow(P, \omega)</math>, is defined to equal <math>|OP|^2 - r^2</math>. |

Note that the power of a point is negative if the point is inside the circle. | Note that the power of a point is negative if the point is inside the circle. | ||

| − | The '''radical axis''' of two circles <math>\omega_1, \omega_2</math> is defined as the locus of the points <math>P</math> such that the [[power of a point|power]] of <math>P</math> with respect to <math>\omega_1</math> and <math>\omega_2</math> are equal. In other words, if <math>O_i, r_i</math> are the center and radius of <math>\omega_i</math>, then a point <math>P</math> is on the radical axis if and only if <cmath>PO_1^2 - r_1^2 = PO_2^2 - r_2^2</cmath> | + | The '''radical axis''' of two non-concentric circles <math>\omega_1, \omega_2</math> is defined as the locus of the points <math>P</math> such that the [[power of a point|power]] of <math>P</math> with respect to <math>\omega_1</math> and <math>\omega_2</math> are equal. In other words, if <math>O_i, r_i</math> are the center and radius of <math>\omega_i</math>, then a point <math>P</math> is on the radical axis if and only if <cmath>|PO_1|^2 - r_1^2 = |PO_2|^2 - r_2^2</cmath> (i.e., the radical axis is the line that one gets when you subtract the equations of two circles). |

==Results== | ==Results== | ||

'''Theorem 1: (Power of a Point)''' | '''Theorem 1: (Power of a Point)''' | ||

If a line drawn through point P intersects circle <math>\omega</math> at points A and B, then <math>|pow(P, \omega)| = PA * PB</math>. | If a line drawn through point P intersects circle <math>\omega</math> at points A and B, then <math>|pow(P, \omega)| = PA * PB</math>. | ||

| + | |||

'''Theorem 2: (Radical Axis Theorem)''' | '''Theorem 2: (Radical Axis Theorem)''' | ||

| Line 19: | Line 23: | ||

c. If they intersect at one point, their radical axis is the common internal tangent. | c. If they intersect at one point, their radical axis is the common internal tangent. | ||

| − | d. If the circles do not intersect, their radical axis is the perpendicular to <math>l</math> through point A, the unique point on <math>l</math> such that <math>pow(A, \omega_1) = pow(A, \omega_2)</math>. | + | d. If the circles do not intersect, and if one does not fully contain the other, their radical axis is the perpendicular to <math>l</math> through point A, the unique point on <math>l</math> such that <math>pow(A, \omega_1) = pow(A, \omega_2)</math>. |

'''Theorem 3: (Radical Axis Concurrence Theorem)''' | '''Theorem 3: (Radical Axis Concurrence Theorem)''' | ||

The three pairwise radical axes of three circles concur at a point, called the '''radical center'''. | The three pairwise radical axes of three circles concur at a point, called the '''radical center'''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Theorem 4: (Radical Centre of Intersecting Circles) (EGMO Theorem 2.9)''' | ||

| + | Let <math>\omega_1</math> and <math>\omega_2</math> be two circles with centers <math>O_1</math> and <math>O_2</math>. Select two points A and B on <math>\omega_1</math> and <math>\omega_2</math>. Then the following are equivalent | ||

| + | *<math>A,B,C,D</math> lie on a circle with center <math>O_3</math> not on line <math>O_1O_2</math>. | ||

| + | *Lines <math>AB</math> and <math>CD</math> intersect on the radical axis of <math>\omega_1</math> and <math>\omega_2</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Theorem 5: (EGMO Lemma 2.11)''' | ||

| + | Let ABC be a triangle and consider a point <math>P</math> in its interior. Suppose that <math>BC</math> is tangent to <math>(ABP)</math> and <math>(ACP)</math>, ray <math>AP</math> bisects <math>BC</math> | ||

==Proofs== | ==Proofs== | ||

| − | Theorem 1 is trivial Power of a Point, and thus is left to the reader as an exercise. (Hint: Draw a line through P and the center.) | + | '''Theorem 1''' is trivial Power of a Point, and thus is left to the reader as an exercise. (Hint: Draw a line through P and the center.) |

| − | Theorem 2 shall be proved here. Assume the circles are <math>\omega_1</math> and <math>\omega_2</math> with centers <math>O_1</math> and <math>O_2</math> and radii <math>r_1</math> and <math>r_2</math>, respectively. (It may be a good idea for you to draw some circles here.) | + | '''Theorem 2''' shall be proved here. Assume the circles are <math>\omega_1</math> and <math>\omega_2</math> with centers <math>O_1</math> and <math>O_2</math> and radii <math>r_1</math> and <math>r_2</math>, respectively. (It may be a good idea for you to draw some circles here.) |

First, we tackle part (b). Suppose the circles intersect at points <math>X</math> and <math>Y</math> and point P lies on <math>XY</math>. Then by Theorem 1 the powers of P with respect to both circles are equal to <math>PX * PY</math>, and hence by transitive <math>pow(P, \omega_1) = pow(P, \omega_2)</math>. Thus, if point P lies on <math>XY</math>, then the powers of P with respect to both circles are equal. | First, we tackle part (b). Suppose the circles intersect at points <math>X</math> and <math>Y</math> and point P lies on <math>XY</math>. Then by Theorem 1 the powers of P with respect to both circles are equal to <math>PX * PY</math>, and hence by transitive <math>pow(P, \omega_1) = pow(P, \omega_2)</math>. Thus, if point P lies on <math>XY</math>, then the powers of P with respect to both circles are equal. | ||

| − | Now, we prove the inverse of the statement just proved; because the inverse is equivalent to the converse, the if and only if would then be proven. Suppose that P does not lie on <math>XY</math>. In particular, line <math>PY</math> does not intersect X. Then <math>PY</math> intersects circles <math>\omega_1</math> and <math>\omega_2</math> a second time at distinct points <math>M</math> and <math>N</math>, respectively. (If <math>PY</math> is tangent to <math>\omega_1</math>, for example, we adopt the convention that <math>P = M</math>; similar conventions hold for <math>\omega_2</math>. Power of a Point still holds in this case. Also, notice that <math>M</math> and <math>N</math> cannot both equal <math>P</math>, as <math>PY</math> cannot be tangent to both circles.) Because <math>PM</math> is not equal to <math>PN</math>, <math> | + | Now, we prove the inverse of the statement just proved; because the inverse is equivalent to the converse, the if and only if would then be proven. Suppose that P does not lie on <math>XY</math>. In particular, line <math>PY</math> does not intersect X. Then <math>PY</math> intersects circles <math>\omega_1</math> and <math>\omega_2</math> a second time at distinct points <math>M</math> and <math>N</math>, respectively. (If <math>PY</math> is tangent to <math>\omega_1</math>, for example, we adopt the convention that <math>P = M</math>; similar conventions hold for <math>\omega_2</math>. Power of a Point still holds in this case. Also, notice that <math>M</math> and <math>N</math> cannot both equal <math>P</math>, as <math>PY</math> cannot be tangent to both circles.) Because <math>PM</math> is not equal to <math>PN</math>, so <math>PM \cdot PY</math> does not equal <math>PN \cdot PY</math>, and thus by Theorem 1 <math>pow(P, \omega_1)</math> is not congruent to <math>pow(P, \omega_2)</math>, as desired. This completes part (b). |

For the remaining parts, we employ a lemma: | For the remaining parts, we employ a lemma: | ||

| Line 41: | Line 53: | ||

''Lemma 2:'' There is an unique point P on line <math>O_1O_2</math> such that <math>pow(P, O_1) = pow(P, O_2)</math>. | ''Lemma 2:'' There is an unique point P on line <math>O_1O_2</math> such that <math>pow(P, O_1) = pow(P, O_2)</math>. | ||

| − | Proof: First show that P lies between <math>O_1</math> and <math>O_2</math>. Then, use the fact that <math>O_1P + PO_2 = O_1O_2</math> (a constant) to prove the lemma. | + | Proof: First show that P lies between <math>O_1</math> and <math>O_2</math> via proof by contradiction, by using a bit of inequality theory and the fact that <math>O_1O_2 > r_1 + r_2</math>. Then, use the fact that <math>O_1P + PO_2 = O_1O_2</math> (a constant) to prove the lemma. |

Lemma 1 shows that every point on the plane can be equivalently mapped to a line on <math>O_1O_2</math>. Lemma 2 shows that only one point in this mapping satisfies the given condition. Combining these two lemmas shows that the radical axis is a line perpendicular to <math>l</math>, completing part (a). | Lemma 1 shows that every point on the plane can be equivalently mapped to a line on <math>O_1O_2</math>. Lemma 2 shows that only one point in this mapping satisfies the given condition. Combining these two lemmas shows that the radical axis is a line perpendicular to <math>l</math>, completing part (a). | ||

| Line 47: | Line 59: | ||

Parts (c) and (d) will be left to the reader as an exercise. (Also, try proving part (b) solely using the lemmas.) | Parts (c) and (d) will be left to the reader as an exercise. (Also, try proving part (b) solely using the lemmas.) | ||

| − | Now, try to prove Theorem 3 on your own! (Hint: Let P be the intersection of two of the radical | + | Now, try to prove '''Theorem 3''' on your own! (Hint: Let P be the intersection of two of the radical axes.)The proof of this theorem along with the proof of '''Theorem 4'''are given in EGMO as '''Example 2.7''' and '''Theorem 2.9'''. |

| + | |||

| + | '''Theorem 5''' | ||

| + | Let <math>AP</math> intersect at <math>BC</math> at <math>M</math> and let <math>(ABP)=\omega_B</math>, <math>(ACP)=\omega_C</math>. Clearly, <math>AP</math> is a radical axis of <math>\omega_B</math>, <math>\omega_C</math>. We see that<cmath>\text{Pow}_{\omega_B}(M)=\text{Pow}_{\omega_C}(M) \implies MB^2=MC^2 \implies MB=MC,</cmath>as desired. | ||

==Exercises== | ==Exercises== | ||

| − | If you haven't already done so, prove the theorems and lemmas outlined in the proofs section. If you | + | If you haven't already done so, prove the theorems and lemmas outlined in the proofs section. |

| + | ''Note:'' No solutions will be provided to the following problems(laziness). If you are stuck, ask on the forum. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Problem 1.''' Two circles <math>P</math> and <math>Q</math> intersect at <math>X</math> and <math>Y</math>. Point <math>A</math> is located on <math>XY</math> such that <math>AP = 10</math> and <math>AQ =</math> <s>15</s> <math>12</math>. If the radius of <math>Q</math> is <math>7</math>, find the radius of <math>P</math>. <span style="color:#ff0000">Note: An error in this problem previously rendered it unsolvable.</span> | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Problem 2.''' Solve [[2009_USAMO_Problems|2009 USAMO Problem 1]]. If you already know how to solve it. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Problem 3.''' Two circles P and Q with radii 1 and 2, respectively, intersect at X and Y. Circle P is to the left of circle Q. Prove that point A is to the left of <math>XY</math> if and only if <math>AQ^2 - AP^2 > 3</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Problem 4.''' Solve [[2012_USAJMO_Problems|2012 USAJMO Problem 1]]. | ||

| − | '' | + | '''Problem 5.''' Does Theorem 2 apply to circles in which one is contained inside the other? How about internally tangent circles? Concentric circles? |

| − | '''Problem | + | '''Problem 6.''' Construct the radical axis of two circles. What happens if one circle encloses the other? |

| − | '''Problem | + | '''Problem 7.''' Solve [[1995_IMO_Problems/Problem_1|1995 IMO Problem 1]] in two different ways. Compare your solutions with the solutions provided. |

| − | + | ==Problems== | |

| + | ===Simple=== | ||

| + | [[File:Point on axes.png|300px|right]] | ||

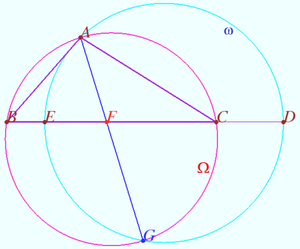

| + | Let triangle <math>\triangle ABC,</math> points <math>D \in BC</math> and <math>E \in BC</math> be given. Denote <math>\Omega = \odot ABC, \omega = \odot AED, G = \omega \cap \Omega \ne A.</math> | ||

| + | Prove that <math>\frac {BF}{FC} = \frac{BE \cdot BD}{CE \cdot CD}.</math> | ||

| − | + | <i><b>Proof</b></i> | |

| + | |||

| + | WLOG, the order of the points is <math>B,E,F,C,D,</math> as shown on diagram. | ||

| + | <cmath>AF \cdot GF = BF \cdot FC = EF \cdot FD</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <cmath>BF \cdot FC = (BE + EF) \cdot FC = EF \cdot (FC + CD) \implies BE \cdot FC = EF \cdot CD.</cmath> | ||

| + | <cmath>BF \cdot FC = BF \cdot (EC - EF) = EF \cdot (BD - BF) \implies BF \cdot EC = EF \cdot BD \implies</cmath> | ||

| + | <cmath>\frac {BE \cdot FC}{CD} = EF = \frac {BF \cdot EC}{BD} \implies | ||

| + | \frac {BF}{FC} = \frac{BE \cdot BD}{CE \cdot CD}.</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Intermediate=== | ||

| + | [[2021_AIME_I_Problems#Problem_13|2021 AIME Problem 13]]. Circles <math>\omega_1</math> and <math>\omega_2</math> with radii <math>961</math> and <math>625</math>, respectively, intersect at distinct points <math>A</math> and <math>B</math>. A third circle <math>\omega</math> is externally tangent to both <math>\omega_1</math> and <math>\omega_2</math>. Suppose line <math>AB</math> intersects <math>\omega</math> at two points <math>P</math> and <math>Q</math> such that the measure of minor arc <math>\widehat{PQ}</math> is <math>120^{\circ}</math>. Find the distance between the centers of <math>\omega_1</math> and <math>\omega_2</math>. | ||

| + | ===Olympiad=== | ||

| + | [[2014_USAMO_Problems#Problem_5|2014 USAMO Problem 5]]. Let <math>ABC</math> be a triangle with orthocenter <math>H</math> and let <math>P</math> be the second intersection of the circumcircle of triangle <math>AHC</math> with the internal bisector of the angle <math>\angle BAC</math>. Let <math>X</math> be the circumcenter of triangle <math>APB</math> and <math>Y</math> the orthocenter of triangle <math>APC</math>. Prove that the length of segment <math>XY</math> is equal to the circumradius of triangle <math>ABC</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[2017_USAMO_Problems#Problem_3|2017 USAMO Problem 3]]. Let <math>ABC</math> be a scalene triangle with circumcircle <math>\Omega</math> and incenter <math>I.</math> Ray <math>AI</math> meets <math>BC</math> at <math>D</math> and <math>\Omega</math> again at <math>M;</math> the circle with diameter <math>DM</math> cuts <math>\Omega</math> again at <math>K.</math> Lines <math>MK</math> and <math>BC</math> meet at <math>S,</math> and <math>N</math> is the midpoint of <math>IS.</math> The circumcircles of <math>\triangle KID</math> and <math>\triangle MAN</math> intersect at points <math>L_1</math> and <math>L.</math> Prove that <math>\Omega</math> passes through the midpoint of either <math>IL_1</math> or <math>IL.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[2012_IMO_Problems#Problem_5|2012 IMO Problem 5]]. Let <math>ABC</math> be a triangle with <math>\angle BCA=90^{\circ}</math>, and let <math>D</math> be the foot of the altitude from <math>C</math>. Let <math>X</math> be a point in the interior of the segment <math>CD</math>. Let <math>K</math> be the point on the segment <math>AX</math> such that <math>BK=BC</math>. Similarly, let <math>L</math> be the point on the segment <math>BX</math> such that <math>AL=AC</math>. Let <math>M=\overline{AL}\cap \overline{BK}</math>. Prove that <math>MK=ML</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==See Also== | ||

| + | [[Category : Geometry]] | ||

Latest revision as of 07:38, 23 May 2024

Contents

Introduction

The theory of radical axis is a priceless geometric tool that can solve formidable geometric problems fairly readily. Problems involving it can be found on many major math olympiad competitions, including the prestigious USAMO. Therefore, any aspiring math olympian should peruse this material carefully, as it may contain the keys to one's future success.

Not all theorems will be fully proven in this text. The objective of this document is to introduce you to some key concepts, and then give you a chance to derive some of the beautiful results on your own. In that way, you will understand and retain the information in here much more solidly. Finally, your newfound knowledge will be tested on a few challenging problems that are exemplary examples on how radical axis theory can be used and why it pertains to that situation. I hope after you read this text, you will become a better math student, armed with another tool to solve difficult problems. But, anyway, good luck.

Definitions

The power of point ![]() with respect to circle

with respect to circle ![]() (with radius

(with radius ![]() and center

and center ![]() ), which shall thereafter be dubbed

), which shall thereafter be dubbed ![]() , is defined to equal

, is defined to equal ![]() .

.

Note that the power of a point is negative if the point is inside the circle.

The radical axis of two non-concentric circles ![]() is defined as the locus of the points

is defined as the locus of the points ![]() such that the power of

such that the power of ![]() with respect to

with respect to ![]() and

and ![]() are equal. In other words, if

are equal. In other words, if ![]() are the center and radius of

are the center and radius of ![]() , then a point

, then a point ![]() is on the radical axis if and only if

is on the radical axis if and only if ![]() (i.e., the radical axis is the line that one gets when you subtract the equations of two circles).

(i.e., the radical axis is the line that one gets when you subtract the equations of two circles).

Results

Theorem 1: (Power of a Point)

If a line drawn through point P intersects circle ![]() at points A and B, then

at points A and B, then ![]() .

.

Theorem 2: (Radical Axis Theorem)

a. The radical axis is a line perpendicular to the line connecting the circles' centers (line ![]() ).

).

b. If the two circles intersect at two common points, their radical axis is the line through these two points.

c. If they intersect at one point, their radical axis is the common internal tangent.

d. If the circles do not intersect, and if one does not fully contain the other, their radical axis is the perpendicular to ![]() through point A, the unique point on

through point A, the unique point on ![]() such that

such that ![]() .

.

Theorem 3: (Radical Axis Concurrence Theorem) The three pairwise radical axes of three circles concur at a point, called the radical center.

Theorem 4: (Radical Centre of Intersecting Circles) (EGMO Theorem 2.9)

Let ![]() and

and ![]() be two circles with centers

be two circles with centers ![]() and

and ![]() . Select two points A and B on

. Select two points A and B on ![]() and

and ![]() . Then the following are equivalent

. Then the following are equivalent

lie on a circle with center

lie on a circle with center  not on line

not on line  .

.- Lines

and

and  intersect on the radical axis of

intersect on the radical axis of  and

and  .

.

Theorem 5: (EGMO Lemma 2.11)

Let ABC be a triangle and consider a point ![]() in its interior. Suppose that

in its interior. Suppose that ![]() is tangent to

is tangent to ![]() and

and ![]() , ray

, ray ![]() bisects

bisects ![]()

Proofs

Theorem 1 is trivial Power of a Point, and thus is left to the reader as an exercise. (Hint: Draw a line through P and the center.)

Theorem 2 shall be proved here. Assume the circles are ![]() and

and ![]() with centers

with centers ![]() and

and ![]() and radii

and radii ![]() and

and ![]() , respectively. (It may be a good idea for you to draw some circles here.)

, respectively. (It may be a good idea for you to draw some circles here.)

First, we tackle part (b). Suppose the circles intersect at points ![]() and

and ![]() and point P lies on

and point P lies on ![]() . Then by Theorem 1 the powers of P with respect to both circles are equal to

. Then by Theorem 1 the powers of P with respect to both circles are equal to ![]() , and hence by transitive

, and hence by transitive ![]() . Thus, if point P lies on

. Thus, if point P lies on ![]() , then the powers of P with respect to both circles are equal.

, then the powers of P with respect to both circles are equal.

Now, we prove the inverse of the statement just proved; because the inverse is equivalent to the converse, the if and only if would then be proven. Suppose that P does not lie on ![]() . In particular, line

. In particular, line ![]() does not intersect X. Then

does not intersect X. Then ![]() intersects circles

intersects circles ![]() and

and ![]() a second time at distinct points

a second time at distinct points ![]() and

and ![]() , respectively. (If

, respectively. (If ![]() is tangent to

is tangent to ![]() , for example, we adopt the convention that

, for example, we adopt the convention that ![]() ; similar conventions hold for

; similar conventions hold for ![]() . Power of a Point still holds in this case. Also, notice that

. Power of a Point still holds in this case. Also, notice that ![]() and

and ![]() cannot both equal

cannot both equal ![]() , as

, as ![]() cannot be tangent to both circles.) Because

cannot be tangent to both circles.) Because ![]() is not equal to

is not equal to ![]() , so

, so ![]() does not equal

does not equal ![]() , and thus by Theorem 1

, and thus by Theorem 1 ![]() is not congruent to

is not congruent to ![]() , as desired. This completes part (b).

, as desired. This completes part (b).

For the remaining parts, we employ a lemma:

Lemma 1: Let ![]() be a point in the plane, and let

be a point in the plane, and let ![]() be the foot of the perpendicular from

be the foot of the perpendicular from ![]() to

to ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() .

.

The proof of the lemma is an easy application of the Pythagorean Theorem and will again be left to the reader as an exercise.

Lemma 2: There is an unique point P on line ![]() such that

such that ![]() .

.

Proof: First show that P lies between ![]() and

and ![]() via proof by contradiction, by using a bit of inequality theory and the fact that

via proof by contradiction, by using a bit of inequality theory and the fact that ![]() . Then, use the fact that

. Then, use the fact that ![]() (a constant) to prove the lemma.

(a constant) to prove the lemma.

Lemma 1 shows that every point on the plane can be equivalently mapped to a line on ![]() . Lemma 2 shows that only one point in this mapping satisfies the given condition. Combining these two lemmas shows that the radical axis is a line perpendicular to

. Lemma 2 shows that only one point in this mapping satisfies the given condition. Combining these two lemmas shows that the radical axis is a line perpendicular to ![]() , completing part (a).

, completing part (a).

Parts (c) and (d) will be left to the reader as an exercise. (Also, try proving part (b) solely using the lemmas.)

Now, try to prove Theorem 3 on your own! (Hint: Let P be the intersection of two of the radical axes.)The proof of this theorem along with the proof of Theorem 4are given in EGMO as Example 2.7 and Theorem 2.9.

Theorem 5

Let ![]() intersect at

intersect at ![]() at

at ![]() and let

and let ![]() ,

, ![]() . Clearly,

. Clearly, ![]() is a radical axis of

is a radical axis of ![]() ,

, ![]() . We see that

. We see that![]() as desired.

as desired.

Exercises

If you haven't already done so, prove the theorems and lemmas outlined in the proofs section. Note: No solutions will be provided to the following problems(laziness). If you are stuck, ask on the forum.

Problem 1. Two circles ![]() and

and ![]() intersect at

intersect at ![]() and

and ![]() . Point

. Point ![]() is located on

is located on ![]() such that

such that ![]() and

and ![]()

15 ![]() . If the radius of

. If the radius of ![]() is

is ![]() , find the radius of

, find the radius of ![]() . Note: An error in this problem previously rendered it unsolvable.

. Note: An error in this problem previously rendered it unsolvable.

Problem 2. Solve 2009 USAMO Problem 1. If you already know how to solve it.

Problem 3. Two circles P and Q with radii 1 and 2, respectively, intersect at X and Y. Circle P is to the left of circle Q. Prove that point A is to the left of ![]() if and only if

if and only if ![]() .

.

Problem 4. Solve 2012 USAJMO Problem 1.

Problem 5. Does Theorem 2 apply to circles in which one is contained inside the other? How about internally tangent circles? Concentric circles?

Problem 6. Construct the radical axis of two circles. What happens if one circle encloses the other?

Problem 7. Solve 1995 IMO Problem 1 in two different ways. Compare your solutions with the solutions provided.

Problems

Simple

Let triangle ![]() points

points ![]() and

and ![]() be given. Denote

be given. Denote ![]() Prove that

Prove that ![]()

Proof

WLOG, the order of the points is ![]() as shown on diagram.

as shown on diagram.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Intermediate

2021 AIME Problem 13. Circles ![]() and

and ![]() with radii

with radii ![]() and

and ![]() , respectively, intersect at distinct points

, respectively, intersect at distinct points ![]() and

and ![]() . A third circle

. A third circle ![]() is externally tangent to both

is externally tangent to both ![]() and

and ![]() . Suppose line

. Suppose line ![]() intersects

intersects ![]() at two points

at two points ![]() and

and ![]() such that the measure of minor arc

such that the measure of minor arc ![]() is

is ![]() . Find the distance between the centers of

. Find the distance between the centers of ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Olympiad

2014 USAMO Problem 5. Let ![]() be a triangle with orthocenter

be a triangle with orthocenter ![]() and let

and let ![]() be the second intersection of the circumcircle of triangle

be the second intersection of the circumcircle of triangle ![]() with the internal bisector of the angle

with the internal bisector of the angle ![]() . Let

. Let ![]() be the circumcenter of triangle

be the circumcenter of triangle ![]() and

and ![]() the orthocenter of triangle

the orthocenter of triangle ![]() . Prove that the length of segment

. Prove that the length of segment ![]() is equal to the circumradius of triangle

is equal to the circumradius of triangle ![]() .

.

2017 USAMO Problem 3. Let ![]() be a scalene triangle with circumcircle

be a scalene triangle with circumcircle ![]() and incenter

and incenter ![]() Ray

Ray ![]() meets

meets ![]() at

at ![]() and

and ![]() again at

again at ![]() the circle with diameter

the circle with diameter ![]() cuts

cuts ![]() again at

again at ![]() Lines

Lines ![]() and

and ![]() meet at

meet at ![]() and

and ![]() is the midpoint of

is the midpoint of ![]() The circumcircles of

The circumcircles of ![]() and

and ![]() intersect at points

intersect at points ![]() and

and ![]() Prove that

Prove that ![]() passes through the midpoint of either

passes through the midpoint of either ![]() or

or ![]()

2012 IMO Problem 5. Let ![]() be a triangle with

be a triangle with ![]() , and let

, and let ![]() be the foot of the altitude from

be the foot of the altitude from ![]() . Let

. Let ![]() be a point in the interior of the segment

be a point in the interior of the segment ![]() . Let

. Let ![]() be the point on the segment

be the point on the segment ![]() such that

such that ![]() . Similarly, let

. Similarly, let ![]() be the point on the segment

be the point on the segment ![]() such that

such that ![]() . Let

. Let ![]() . Prove that

. Prove that ![]() .

.