1972 IMO Problems/Problem 6

Contents

[hide]Problem

Given four distinct parallel planes, prove that there exists a regular tetrahedron with a vertex on each plane.

Solution 1

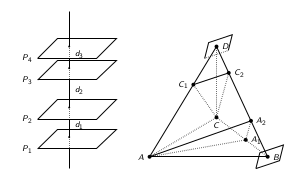

Let our planes be ![]() , which we assume to be parallel to the

, which we assume to be parallel to the ![]() -plane, listed in the increasing order of their

-plane, listed in the increasing order of their ![]() -coordinates. First take a plane

-coordinates. First take a plane ![]() orthogonal to

orthogonal to ![]() , which cuts

, which cuts ![]() along three lines

along three lines ![]() . On these three lines, take three vertices

. On these three lines, take three vertices ![]() respectively of an equilateral triangle (it is well-known that this is possible; in fact, the problem here is the

respectively of an equilateral triangle (it is well-known that this is possible; in fact, the problem here is the ![]() -dimensional version of this), and then complete the two regular tetrahedra

-dimensional version of this), and then complete the two regular tetrahedra ![]() having

having ![]() as one of their faces. Both

as one of their faces. Both ![]() lie below

lie below ![]() .

.

Now take another plane ![]() and repeat the construction above. If

and repeat the construction above. If ![]() makes a small enough angle with the

makes a small enough angle with the ![]() 's, one of the

's, one of the ![]() 's we get this time must lie above

's we get this time must lie above ![]() . Now, if we move the initial position of

. Now, if we move the initial position of ![]() towards the new one continuously and record the

towards the new one continuously and record the ![]() -coordinates of

-coordinates of ![]() , these will be continuous functions of the angle that

, these will be continuous functions of the angle that ![]() makes with

makes with ![]() , and for one of the points

, and for one of the points ![]() the

the ![]() -coordinate will move continuously from being smaller than that of

-coordinate will move continuously from being smaller than that of ![]() to being larger than it, meaning that at some point, one of the points

to being larger than it, meaning that at some point, one of the points ![]() will lie on

will lie on ![]() , and this is what we want.

, and this is what we want.

The above solution was posted and copyrighted by grobber. The original thread for this problem can be found here: [1]

Solution 2

Let's denote the (directed) distance between two parallel planes p and p' by d (p; p'), and the (directed) distance between two parallel lines g and g' by d (g; g'). (Directed distances are defined as follows: If ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , ... is a family of parallel planes in space, then we choose a unit vector

, ... is a family of parallel planes in space, then we choose a unit vector ![]() perpendicular to all of these planes (there are two such unit vectors, and we have to choose one of them), and then, by the directed distance between two of these planes

perpendicular to all of these planes (there are two such unit vectors, and we have to choose one of them), and then, by the directed distance between two of these planes ![]() and

and ![]() , we denote the real number k such that the translation with translation vector

, we denote the real number k such that the translation with translation vector ![]() maps the plane

maps the plane ![]() to the plane

to the plane ![]() . Similarly, we define the directed distance between two of a family of parallel lines in a plane.)

. Similarly, we define the directed distance between two of a family of parallel lines in a plane.)

The problem can be rewritten as follows: Given four distinct parallel planes ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() in space, prove that there exists a regular tetrahedron XYZW such that

in space, prove that there exists a regular tetrahedron XYZW such that ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() .

.

In order to do this, it is enough to find a regular tetrahedron ABCD somewhere in space and four parallel planes ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() such that

such that ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() . In fact, once we have found such a tetrahedron ABCD and such planes

. In fact, once we have found such a tetrahedron ABCD and such planes ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , then, because of

, then, because of ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() , there exists a similitude transformation which maps the planes

, there exists a similitude transformation which maps the planes ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() to the planes

to the planes ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ; this similitude transformation will then obviously map the regular tetrahedron ABCD with

; this similitude transformation will then obviously map the regular tetrahedron ABCD with ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() to a regular tetrahedron XYZW with

to a regular tetrahedron XYZW with ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ; hence, the existence of such a tetrahedron XYZW will be proven, and the problem will be solved.

; hence, the existence of such a tetrahedron XYZW will be proven, and the problem will be solved.

So consider a regular tetrahedron ABCD lying arbitrarily in space; we try to find four parallel planes ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() such that

such that ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

In fact, we start working in the plane ABC. Let T be the point on the line AC such that ![]() (where the segments AT and TC are directed). Let

(where the segments AT and TC are directed). Let ![]() be the line BT, and let

be the line BT, and let ![]() and

and ![]() be the parallels to the line

be the parallels to the line ![]() through the points A and C, respectively. Then, the lines

through the points A and C, respectively. Then, the lines ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() are parallel and, by Thales,

are parallel and, by Thales, ![]() . Thus,

. Thus, ![]() . Now, denote by

. Now, denote by ![]() the line in the plane ABC which is parallel to the lines

the line in the plane ABC which is parallel to the lines ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() and satisfies

and satisfies ![]() .

.

Now, let ![]() be the plane passing through the line

be the plane passing through the line ![]() and the point D. Let

and the point D. Let ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() be the planes parallel to

be the planes parallel to ![]() and passing through the lines

and passing through the lines ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , respectively (of course, we can construct such planes since the lines

, respectively (of course, we can construct such planes since the lines ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() are parallel to

are parallel to ![]() ). Thus, we have found four parallel planes

). Thus, we have found four parallel planes ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() such that

such that ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and these planes obviously satisfy

, and these planes obviously satisfy ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() , we thus have

, we thus have ![]() . Hence, according to the above, the problem is solved.

. Hence, according to the above, the problem is solved.

The above solution was posted and copyrighted by darij grinberg. The original thread for this problem can be found here: [2]

Remarks (added by pf02, May 2025)

1. The first "solution" is based on a good idea, but it is so incomplete (it contains so mach hand-waiving) that it can not be called a solution. Here are the issues with this "solution":

a. The first problem (minor) is the statement "On these three lines,

take three vertices ![]() respectively of an equilateral

triangle (it is well-known that this is possible...)". This is *not*

well known, it should be proven.

respectively of an equilateral

triangle (it is well-known that this is possible...)". This is *not*

well known, it should be proven.

b. The second problem (a more serious one) is the statement that "If

![]() makes a small enough angle with the

makes a small enough angle with the ![]() 's, one of the

's, one of the

![]() 's we get this time must lie above

's we get this time must lie above ![]() ". This is probably

true, but not obvious at all, and it should have a proof.

". This is probably

true, but not obvious at all, and it should have a proof.

c. The third problem (this is so serious that it is a "show stopper")

is the assumption (not stated explicitly) that the ![]() -coordinates

of

-coordinates

of ![]() as functions of the angle

as functions of the angle ![]() between

between ![]() and

and

![]() are continuous functions. This is not even true as stated,

it depends on the choice of

are continuous functions. This is not even true as stated,

it depends on the choice of ![]() .

.

As I said, the idea is good, and this could be turned into a solution to the problem. I leave this task to the diligent reader.

2. Below, I will give another solution to the problem. It is similar to solution 2, but different enough to warrant writing it down. Both this solution, and solution 2, show that in fact, the tetrahedron does not have to be regular. The problem could be restated as "Given four distinct parallel planes and a tetrahedron, prove that there exists a tetrahedron similar to the given one with a vertex on each plane."

Solution 3

As I remarked, this solution is similar with the previous one. Let

![]() be the four planes. We can assume they are

horizontal (in some

be the four planes. We can assume they are

horizontal (in some ![]() coordinate system in which the

coordinate system in which the ![]() axis is vertical) and that their

axis is vertical) and that their ![]() coordinates are in increasing

order. Let

coordinates are in increasing

order. Let ![]() be the distance between

be the distance between ![]() ,

, ![]() be the

distance between

be the

distance between ![]() , and

, and ![]() be the distance between

be the distance between

![]() .

.

Now consider the tetrahedron ![]() . Take

. Take ![]() and

and ![]() such that

such that

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() .

.

Note that (3) and (4) imply

![]()

![]() .

.

(1) and (5) imply that ![]() . Also,

(2) and (6) imply that

. Also,

(2) and (6) imply that ![]() . From these

it follows that the planes

. From these

it follows that the planes ![]() and

and ![]() are

parallel.

are

parallel.

Now take two planes ![]() through

through ![]() , and

, and ![]() through

through ![]() parallel to the parallel planes

parallel to the parallel planes ![]() and

and ![]() .

If we denote

.

If we denote ![]() the distances between

the distances between ![]() and

and ![]() , the plane

, the plane ![]() and

and ![]() , and

finally,

, and

finally, ![]() and

and ![]() , then (5) and (6) imply that

, then (5) and (6) imply that

![]() and

and

![]() .

.

From this it follows that we can find a similar transformation

in the 3D space which takes our four planes into the four planes

![]() . To make this explicit, we first take a

rotation followed by a translation which takes

. To make this explicit, we first take a

rotation followed by a translation which takes ![]() into

into ![]() .

Now we take a scaling (with suitable origin and factor) which

keeps

.

Now we take a scaling (with suitable origin and factor) which

keeps ![]() in place, and maps the image of

in place, and maps the image of ![]() obtained

so far into

obtained

so far into ![]() . Because of (7), the image of

. Because of (7), the image of ![]() will

map into

will

map into ![]() and the image of

and the image of ![]() will map into

will map into ![]() .

.

Through these transformations, the image of the tetrahedron ![]() will map into a similar tetrahedron with its vertices on

will map into a similar tetrahedron with its vertices on

![]() .

.

[Solution by pf02, May 2025]

See Also

| 1972 IMO (Problems) • Resources | ||

| Preceded by Problem 5 |

1 • 2 • 3 • 4 • 5 • 6 | Followed by Last Question |

| All IMO Problems and Solutions | ||