Difference between revisions of "2018 AIME I Problems/Problem 1"

(→Solution) |

Smbellanki (talk | contribs) m (→Solution 1) |

||

| (40 intermediate revisions by 25 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

Let <math>S</math> be the number of ordered pairs of integers <math>(a,b)</math> with <math>1 \leq a \leq 100</math> and <math>b \geq 0</math> such that the polynomial <math>x^2+ax+b</math> can be factored into the product of two (not necessarily distinct) linear factors with integer coefficients. Find the remainder when <math>S</math> is divided by <math>1000</math>. | Let <math>S</math> be the number of ordered pairs of integers <math>(a,b)</math> with <math>1 \leq a \leq 100</math> and <math>b \geq 0</math> such that the polynomial <math>x^2+ax+b</math> can be factored into the product of two (not necessarily distinct) linear factors with integer coefficients. Find the remainder when <math>S</math> is divided by <math>1000</math>. | ||

| − | ==Solution== | + | ==Solution 1== |

| − | + | Let the linear factors be <math>(x+c)(x+d)</math>. | |

| − | Then, | + | Then, <math>a=c+d</math> and <math>b=cd</math>. |

| − | We know that <math>1\le a\le 100</math> and <math>b\ge 0</math>, so <math>c</math> and <math>d</math> both have to be | + | We know that <math>1\le a\le 100</math> and <math>b\ge 0</math>, so <math>c</math> and <math>d</math> both have to be non-negative |

However, <math>a</math> cannot be <math>0</math>, so at least one of <math>c</math> and <math>d</math> must be greater than <math>0</math>, ie positive. | However, <math>a</math> cannot be <math>0</math>, so at least one of <math>c</math> and <math>d</math> must be greater than <math>0</math>, ie positive. | ||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

Also, <math>a</math> cannot be greater than <math>100</math>, so <math>c+d</math> must be less than or equal to <math>100</math>. | Also, <math>a</math> cannot be greater than <math>100</math>, so <math>c+d</math> must be less than or equal to <math>100</math>. | ||

| − | Essentially, if we plot the solutions, we get a triangle on the coordinate plane with vertices <math>(0,0), (0, 100),</math> and <math>(100,0)</math>. Remember that <math>(0,0)</math> does not work, so there is a square with top right corner <math>(1,1)</math>. | + | Essentially, if we plot the solutions, we get a triangle on the coordinate plane with vertices <math>(0,0), (0, 100),</math> and <math>(100,0)</math>. Remember that <math>(0,0)</math> does not work, so there is a square with the top right corner <math>(1,1)</math>. |

| − | Note that <math>c</math> and <math>d</math> are interchangeable | + | Note that <math>c</math> and <math>d</math> are interchangeable since they end up as <math>a</math> and <math>b</math> in the end anyways. Thus, we simply draw a line from <math>(1,1)</math> to <math>(50,50)</math>, designating one of the halves as our solution (since the other side is simply the coordinates flipped). |

We note that the pattern from <math>(1,1)</math> to <math>(50,50)</math> is <math>2+3+4+\dots+51</math> solutions and from <math>(51, 49)</math> to <math>(100,0)</math> is <math>50+49+48+\dots+1</math> solutions, since we can decrease the <math>y</math>-value by <math>1</math> until <math>0</math> for each coordinate. | We note that the pattern from <math>(1,1)</math> to <math>(50,50)</math> is <math>2+3+4+\dots+51</math> solutions and from <math>(51, 49)</math> to <math>(100,0)</math> is <math>50+49+48+\dots+1</math> solutions, since we can decrease the <math>y</math>-value by <math>1</math> until <math>0</math> for each coordinate. | ||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

Thus, the answer is: <cmath>\boxed{600}.</cmath> | Thus, the answer is: <cmath>\boxed{600}.</cmath> | ||

| + | ~Minor edit by Yiyj1 | ||

| − | Solution 2 | + | ==Solution 2== |

| − | + | Similar to the previous solution, we plot the triangle and cut it in half. Then, we find the number of boundary points, which is <math>101+51+51-3</math>, or just <math>200</math>. Using Pick's theorem, we know that the area of the half-triangle, which is <math>2500</math>, is just <math>I+100-1</math>. That means that there are <math>2401</math> interior points, plus <math>200</math> boundary points, which is <math>2601</math>. However, <math>(0,0)</math> does not work, so the answer is <cmath>\boxed{600}.</cmath> | |

| − | + | ==Solution 3 (less complicated)== | |

| + | Notice that for <math>x^2+ax+b</math> to be true, for every <math>a</math>, <math>b</math> will always be the product of the possibilities of how to add two integers to <math>a</math>. For example, if <math>a=3</math>, <math>b</math> will be the product of <math>(3,0)</math> and <math>(2,1)</math>, as those two sets are the only possibilities of adding two integers to <math>a</math>. Note that order does not matter. If we just do some simple casework, we find out that: | ||

| − | + | if <math>a</math> is odd, there will always be <math>\left\lceil\frac{a}{2}\right\rceil</math> <math>\left(\text{which is also }\frac{a+1}{2}\right)</math> possibilities of adding two integers to <math>a</math>. | |

| − | + | if <math>a</math> is even, there will always be <math>\frac{a}{2}+1</math> possibilities of adding two integers to <math>a</math>. | |

| − | + | Using the casework, we have <math>1+2+2+3+3+...50+50+51</math> possibilities. This will mean that the answer is <cmath>\frac{(1+51)\cdot100}{2}\Rightarrow52\cdot50=2600</cmath> possibilities. | |

| − | For instance, a=2 and a=3 both have 2 b-values. a=4 and a=5 both have 3 b-values. | + | Thus, our solution is <math>2600\bmod {1000}\equiv\boxed{600}</math>. |

| + | |||

| + | Solution by IronicNinja~ | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 4== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Let's write the linear factors as <math>(x+n)(x+m)</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Then we can write them as: <math>a=n+m, b=nm</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>n</math> or <math>m</math> has to be a positive integer as a cannot be 0. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>n+m</math> has to be between <math>1</math> and <math>100</math>, as a cannot be over <math>100</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Excluding <math>a=1</math>, we can see there is always a pair of <math>2</math> a-values for a certain amount of b-values. | ||

| + | |||

| + | For instance, <math>a=2</math> and <math>a=3</math> both have <math>2</math> b-values. <math>a=4</math> and <math>a=5</math> both have <math>3</math> b-values. | ||

We notice the pattern of the number of b-values in relation to the a-values: | We notice the pattern of the number of b-values in relation to the a-values: | ||

| − | 1, 2, 2, 3, 3, 4, 4… | + | <math>1, 2, 2, 3, 3, 4, 4…</math> |

| + | |||

| + | === Ending 1 === | ||

| + | We see the pattern <math>1, 2; 2, 3; 3, 4; ...</math>. There are 50 pairs of <math>i, i+1</math> in this pattern, and each pair sums to <math>2i+1</math>. So the pattern condenses to <math>3, 5, 7, ...</math> for 50 terms. This is just <math>1+3+5+...</math> for 51 terms, minus <math>1</math>, or <math>51^2-1=2601-1=2600\implies\boxed{600}</math>. | ||

| − | + | ~ Firebolt360 | |

| + | === Ending 2 === | ||

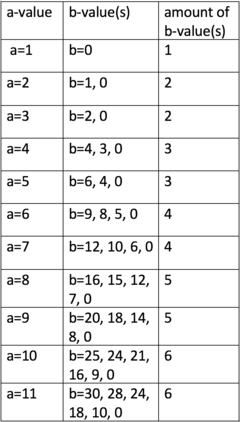

The following link is the URL to the graph I drew showing the relationship between a-values and b-values | The following link is the URL to the graph I drew showing the relationship between a-values and b-values | ||

http://artofproblemsolving.com/wiki/index.php?title=File:Screen_Shot_2018-04-30_at_8.15.00_PM.png#file | http://artofproblemsolving.com/wiki/index.php?title=File:Screen_Shot_2018-04-30_at_8.15.00_PM.png#file | ||

| + | [[File:Screen Shot 2018-04-30 at 8.15.00 PM.png|thumb|240px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | The pattern continues until <math>a=100</math>, and in total, there are <math>49</math> pairs of a-value with the same amount of b-values. The two lone a-values without a pair are, the (<math>a=1</math>, amount of b-values=1) in the beginning, and (<math>a=100</math>, amount of b-values=51) in the end. | ||

| − | Then, we add numbers from the opposite ends of the spectrum, and quickly notice that there are 50 pairs each with a sum of 52. | + | Then, we add numbers from the opposite ends of the spectrum, and quickly notice that there are <math>50</math> pairs each with a sum of <math>52</math>. <math>52\cdot50</math> gives <math>2600</math> ordered pairs: |

| − | 1+51, 2+50, 2+50, 3+49, 3+49, 4+48, 4+48… | + | <math>1+51, 2+50, 2+50, 3+49, 3+49, 4+48, 4+48…</math> |

| − | When divided by 1000, it gives the remainder 600, the answer. | + | When divided by <math>1000</math>, it gives the remainder <math>\boxed{600}</math>, the answer. |

Solution provided by- Yonglao | Solution provided by- Yonglao | ||

| + | Slightly modified by Afly | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Remark : This solution works because | ||

| + | no distinct <math>(a,b), (c,d)</math> exist such that <math>a+b=c+d,ab=cd</math> unless <math>a = d</math> and <math>b = c</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 5== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Let's say that the quadratic <math>x^2 + ax + b</math> can be factored into <math>(x+c)(x+d)</math> where <math>c</math> and <math>d</math> are non-negative numbers. We can't have both of them zero because <math>a</math> would not be within bounds. Also, <math>c+d \leq 100</math>. Assume that <math>c < d</math>. <math>d</math> can be written as <math>c + x</math> where <math>x \geq 0</math>. Therefore, <math>c + d = 2c + x \leq 100</math>. To find the amount of ordered pairs, we must consider how many values of <math>x</math> are possible for each value of <math>c</math>. The amount of possible values of <math>x</math> is given by <math>100 - 2c + 1</math>. The <math>+1</math> is the case where <math>c = d</math>. We don't include the case where <math>c = d = 0</math>, so we must subtract a case from our total. The amount of ordered pairs of <math>(a,b)</math> is: | ||

| + | <cmath>\left(\sum_{c=0}^{50} (100 - 2c + 1)\right) - 1</cmath> | ||

| + | This is an arithmetic progression. <cmath>\frac{(101 + 1)(51)}{2} - 1 = 2601 - 1 = 2600</cmath> | ||

| + | When divided by <math>1000</math>, it gives the remainder <math>\boxed{600}</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ~Zeric Hang | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 6(simple)== | ||

| + | By Vietas, the sum of the roots is <math>-a</math> and the product is <math>b</math>. Therefore, both roots are nonpositive. For each value of <math>a</math> from <math>1</math> to <math>100</math>, the number of <math>b</math> values is the number of ways to sum two numbers between <math>0</math> and <math>a-1</math> inclusive to <math>a</math>. This is just <math>1 + 2 + 2 + 3 + 3 +... 50 + 50 + 51 = 2600</math>. Thus, the answer is <math>\boxed{600}</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | -bron jiang | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 7 (less room for error)== | ||

| + | Similar to solution 1 we plot the triangle and half it. From dividing the triangle in half we are removing the other half of answers that are just flipped coordinates. We notice that we can measure the length of the longest side of the half triangle which is just from <math>0</math> to <math>100</math>, so the number of points on that line is is <math>101</math>. The next row has length <math>99</math>, the one after that has length <math>97</math>, and so on. We simply add this arithmetic series of odd integers <math>101+99+97+...+1</math>. | ||

| + | This is <cmath>\frac{(101+1)(51)}{2} = 2601</cmath> | ||

| + | Or you can notice that this is the sum of the first <math>51</math> odd terms, which is just <math>51^2 = 2601</math>. | ||

| + | However, <math>(0,0)</math> is the singular coordinate that does not work, so the answer is <math>(2601-1)\bmod {1000}\equiv\boxed{600}</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Solution by Damian Kim~ | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 8 (Sticks and stones)== | ||

| + | Letting <math>-r</math> and <math>-q</math> be the roots, we must find the number of unordered pairs <math>(r,q)</math> such that <math>1 \le r+q \le 100.</math> To do this we define three boxes: <math>r, q,</math> and <math>t</math> for "trash." For example, if we had <math>t=77,</math> we would have any arrangement of <math>r</math> and <math>q</math> summing to <math>23.</math> Note that we cannot have <math>t=100,</math> subtracting one from our total. By stars and bars, we have that the number of ordered pairs <math>(r,q)</math> is <math>{102 \choose 2} - 1 = 5150.</math> However, we are not done: we have double-counted cases such as <math>(1,2)</math> and <math>(2,1)</math> but not cases such as <math>(4,4).</math> Thus our answer will be <math>\frac{5150 - 50}{2} + 50 \pmod {100} = \boxed{600}.</math> | ||

| + | ~ab2024 | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 9 (Official MAA)== | ||

| + | The factoring condition is equivalent to the discriminant <math>a^2-4b</math> being equal to <math>c^2</math> for some integer <math>c.</math> Because <math>b\ge 0,</math> the equation <math>4b=(a-c)(a+c)</math> shows that the existence of such a <math>b</math> is equivalent to <math>a\equiv c\pmod 2</math> with <math>0<c\le a.</math> Thus the number of ordered pairs is <cmath>S=\sum_{a=1}^{100}\left\lceil\frac{a+1}{2}\right\rceil=2600.</cmath> The requested remainder is <math>600.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Video Solution== | ||

| + | |||

| + | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WVtbD8x9fCM | ||

| + | ~Shreyas S | ||

==See Also== | ==See Also== | ||

{{AIME box|year=2018|n=I|before=First Problem|num-a=2}} | {{AIME box|year=2018|n=I|before=First Problem|num-a=2}} | ||

{{MAA Notice}} | {{MAA Notice}} | ||

Latest revision as of 19:57, 20 June 2024

Contents

[hide]Problem 1

Let ![]() be the number of ordered pairs of integers

be the number of ordered pairs of integers ![]() with

with ![]() and

and ![]() such that the polynomial

such that the polynomial ![]() can be factored into the product of two (not necessarily distinct) linear factors with integer coefficients. Find the remainder when

can be factored into the product of two (not necessarily distinct) linear factors with integer coefficients. Find the remainder when ![]() is divided by

is divided by ![]() .

.

Solution 1

Let the linear factors be ![]() .

.

Then, ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

We know that ![]() and

and ![]() , so

, so ![]() and

and ![]() both have to be non-negative

both have to be non-negative

However, ![]() cannot be

cannot be ![]() , so at least one of

, so at least one of ![]() and

and ![]() must be greater than

must be greater than ![]() , ie positive.

, ie positive.

Also, ![]() cannot be greater than

cannot be greater than ![]() , so

, so ![]() must be less than or equal to

must be less than or equal to ![]() .

.

Essentially, if we plot the solutions, we get a triangle on the coordinate plane with vertices ![]() and

and ![]() . Remember that

. Remember that ![]() does not work, so there is a square with the top right corner

does not work, so there is a square with the top right corner ![]() .

.

Note that ![]() and

and ![]() are interchangeable since they end up as

are interchangeable since they end up as ![]() and

and ![]() in the end anyways. Thus, we simply draw a line from

in the end anyways. Thus, we simply draw a line from ![]() to

to ![]() , designating one of the halves as our solution (since the other side is simply the coordinates flipped).

, designating one of the halves as our solution (since the other side is simply the coordinates flipped).

We note that the pattern from ![]() to

to ![]() is

is ![]() solutions and from

solutions and from ![]() to

to ![]() is

is ![]() solutions, since we can decrease the

solutions, since we can decrease the ![]() -value by

-value by ![]() until

until ![]() for each coordinate.

for each coordinate.

Adding up gives ![]() This gives us

This gives us ![]() , and

, and ![]()

Thus, the answer is: ![]()

~Minor edit by Yiyj1

Solution 2

Similar to the previous solution, we plot the triangle and cut it in half. Then, we find the number of boundary points, which is ![]() , or just

, or just ![]() . Using Pick's theorem, we know that the area of the half-triangle, which is

. Using Pick's theorem, we know that the area of the half-triangle, which is ![]() , is just

, is just ![]() . That means that there are

. That means that there are ![]() interior points, plus

interior points, plus ![]() boundary points, which is

boundary points, which is ![]() . However,

. However, ![]() does not work, so the answer is

does not work, so the answer is ![]()

Solution 3 (less complicated)

Notice that for ![]() to be true, for every

to be true, for every ![]() ,

, ![]() will always be the product of the possibilities of how to add two integers to

will always be the product of the possibilities of how to add two integers to ![]() . For example, if

. For example, if ![]() ,

, ![]() will be the product of

will be the product of ![]() and

and ![]() , as those two sets are the only possibilities of adding two integers to

, as those two sets are the only possibilities of adding two integers to ![]() . Note that order does not matter. If we just do some simple casework, we find out that:

. Note that order does not matter. If we just do some simple casework, we find out that:

if ![]() is odd, there will always be

is odd, there will always be ![]()

![]() possibilities of adding two integers to

possibilities of adding two integers to ![]() .

.

if ![]() is even, there will always be

is even, there will always be ![]() possibilities of adding two integers to

possibilities of adding two integers to ![]() .

.

Using the casework, we have ![]() possibilities. This will mean that the answer is

possibilities. This will mean that the answer is ![]() possibilities.

possibilities.

Thus, our solution is ![]() .

.

Solution by IronicNinja~

Solution 4

Let's write the linear factors as ![]() .

.

Then we can write them as: ![]() .

.

![]() or

or ![]() has to be a positive integer as a cannot be 0.

has to be a positive integer as a cannot be 0.

![]() has to be between

has to be between ![]() and

and ![]() , as a cannot be over

, as a cannot be over ![]() .

.

Excluding ![]() , we can see there is always a pair of

, we can see there is always a pair of ![]() a-values for a certain amount of b-values.

a-values for a certain amount of b-values.

For instance, ![]() and

and ![]() both have

both have ![]() b-values.

b-values. ![]() and

and ![]() both have

both have ![]() b-values.

b-values.

We notice the pattern of the number of b-values in relation to the a-values:

![]()

Ending 1

We see the pattern ![]() . There are 50 pairs of

. There are 50 pairs of ![]() in this pattern, and each pair sums to

in this pattern, and each pair sums to ![]() . So the pattern condenses to

. So the pattern condenses to ![]() for 50 terms. This is just

for 50 terms. This is just ![]() for 51 terms, minus

for 51 terms, minus ![]() , or

, or ![]() .

.

~ Firebolt360

Ending 2

The following link is the URL to the graph I drew showing the relationship between a-values and b-values http://artofproblemsolving.com/wiki/index.php?title=File:Screen_Shot_2018-04-30_at_8.15.00_PM.png#file

The pattern continues until ![]() , and in total, there are

, and in total, there are ![]() pairs of a-value with the same amount of b-values. The two lone a-values without a pair are, the (

pairs of a-value with the same amount of b-values. The two lone a-values without a pair are, the (![]() , amount of b-values=1) in the beginning, and (

, amount of b-values=1) in the beginning, and (![]() , amount of b-values=51) in the end.

, amount of b-values=51) in the end.

Then, we add numbers from the opposite ends of the spectrum, and quickly notice that there are ![]() pairs each with a sum of

pairs each with a sum of ![]() .

. ![]() gives

gives ![]() ordered pairs:

ordered pairs:

![]()

When divided by ![]() , it gives the remainder

, it gives the remainder ![]() , the answer.

, the answer.

Solution provided by- Yonglao Slightly modified by Afly

Remark : This solution works because

no distinct ![]() exist such that

exist such that ![]() unless

unless ![]() and

and ![]()

Solution 5

Let's say that the quadratic ![]() can be factored into

can be factored into ![]() where

where ![]() and

and ![]() are non-negative numbers. We can't have both of them zero because

are non-negative numbers. We can't have both of them zero because ![]() would not be within bounds. Also,

would not be within bounds. Also, ![]() . Assume that

. Assume that ![]() .

. ![]() can be written as

can be written as ![]() where

where ![]() . Therefore,

. Therefore, ![]() . To find the amount of ordered pairs, we must consider how many values of

. To find the amount of ordered pairs, we must consider how many values of ![]() are possible for each value of

are possible for each value of ![]() . The amount of possible values of

. The amount of possible values of ![]() is given by

is given by ![]() . The

. The ![]() is the case where

is the case where ![]() . We don't include the case where

. We don't include the case where ![]() , so we must subtract a case from our total. The amount of ordered pairs of

, so we must subtract a case from our total. The amount of ordered pairs of ![]() is:

is:

![\[\left(\sum_{c=0}^{50} (100 - 2c + 1)\right) - 1\]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/b/7/c/b7c7d0ddcb83bd0b953209d8f8991dd50854b70c.png) This is an arithmetic progression.

This is an arithmetic progression. ![]() When divided by

When divided by ![]() , it gives the remainder

, it gives the remainder ![]()

~Zeric Hang

Solution 6(simple)

By Vietas, the sum of the roots is ![]() and the product is

and the product is ![]() . Therefore, both roots are nonpositive. For each value of

. Therefore, both roots are nonpositive. For each value of ![]() from

from ![]() to

to ![]() , the number of

, the number of ![]() values is the number of ways to sum two numbers between

values is the number of ways to sum two numbers between ![]() and

and ![]() inclusive to

inclusive to ![]() . This is just

. This is just ![]() . Thus, the answer is

. Thus, the answer is ![]()

-bron jiang

Solution 7 (less room for error)

Similar to solution 1 we plot the triangle and half it. From dividing the triangle in half we are removing the other half of answers that are just flipped coordinates. We notice that we can measure the length of the longest side of the half triangle which is just from ![]() to

to ![]() , so the number of points on that line is is

, so the number of points on that line is is ![]() . The next row has length

. The next row has length ![]() , the one after that has length

, the one after that has length ![]() , and so on. We simply add this arithmetic series of odd integers

, and so on. We simply add this arithmetic series of odd integers ![]() .

This is

.

This is ![]() Or you can notice that this is the sum of the first

Or you can notice that this is the sum of the first ![]() odd terms, which is just

odd terms, which is just ![]() .

However,

.

However, ![]() is the singular coordinate that does not work, so the answer is

is the singular coordinate that does not work, so the answer is ![]()

Solution by Damian Kim~

Solution 8 (Sticks and stones)

Letting ![]() and

and ![]() be the roots, we must find the number of unordered pairs

be the roots, we must find the number of unordered pairs ![]() such that

such that ![]() To do this we define three boxes:

To do this we define three boxes: ![]() and

and ![]() for "trash." For example, if we had

for "trash." For example, if we had ![]() we would have any arrangement of

we would have any arrangement of ![]() and

and ![]() summing to

summing to ![]() Note that we cannot have

Note that we cannot have ![]() subtracting one from our total. By stars and bars, we have that the number of ordered pairs

subtracting one from our total. By stars and bars, we have that the number of ordered pairs ![]() is

is  However, we are not done: we have double-counted cases such as

However, we are not done: we have double-counted cases such as ![]() and

and ![]() but not cases such as

but not cases such as ![]() Thus our answer will be

Thus our answer will be ![]() ~ab2024

~ab2024

Solution 9 (Official MAA)

The factoring condition is equivalent to the discriminant ![]() being equal to

being equal to ![]() for some integer

for some integer ![]() Because

Because ![]() the equation

the equation ![]() shows that the existence of such a

shows that the existence of such a ![]() is equivalent to

is equivalent to ![]() with

with ![]() Thus the number of ordered pairs is

Thus the number of ordered pairs is ![\[S=\sum_{a=1}^{100}\left\lceil\frac{a+1}{2}\right\rceil=2600.\]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/1/0/5/10523518641c4de5069db7efde492b10c94721ba.png) The requested remainder is

The requested remainder is ![]()

Video Solution

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WVtbD8x9fCM ~Shreyas S

See Also

| 2018 AIME I (Problems • Answer Key • Resources) | ||

| Preceded by First Problem |

Followed by Problem 2 | |

| 1 • 2 • 3 • 4 • 5 • 6 • 7 • 8 • 9 • 10 • 11 • 12 • 13 • 14 • 15 | ||

| All AIME Problems and Solutions | ||

The problems on this page are copyrighted by the Mathematical Association of America's American Mathematics Competitions.