Difference between revisions of "2021 Fall AMC 12A Problems/Problem 13"

(→Solution 3 (Easy Test)) |

(→Solution 9) |

||

| (95 intermediate revisions by 10 users not shown) | |||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

==Diagram== | ==Diagram== | ||

| + | <asy> | ||

| + | /* Made by MRENTHUSIASM */ | ||

| + | size(250); | ||

| − | = | + | real xMin = -1; |

| − | + | real xMax = 4; | |

| + | real yMin = -1; | ||

| + | real yMax = 4; | ||

| + | real k = (1+sqrt(5))/2; | ||

| − | + | pair O; | |

| + | O = origin; | ||

| − | By the Angle Bisector Theorem, we | + | draw(anglemark(dir((1,1)),O,dir((1,k)),20), red); |

| + | draw(anglemark(dir((1,k)),O,dir((1,3)),20), red); | ||

| + | add(pathticks(anglemark(dir((1,1)),O,dir((1,k)),20), n = 1, r = 0.05, s = 5, red)); | ||

| + | add(pathticks(anglemark(dir((1,k)),O,dir((1,3)),20), n = 1, r = 0.05, s = 5, red)); | ||

| + | draw((xMin,0)--(xMax,0),black+linewidth(1.5),EndArrow(5)); | ||

| + | draw((0,yMin)--(0,yMax),black+linewidth(1.5),EndArrow(5)); | ||

| + | label("$x$",(xMax,0),(2,0)); | ||

| + | label("$y$",(0,yMax),(0,2)); | ||

| + | label("$y=x$",4*dir((1,1))); | ||

| + | label("$y=3x$",4*dir((1,3))); | ||

| + | label("$y=kx$",4*dir((1,k))); | ||

| + | |||

| + | draw(O--3.75*dir((1,1))^^O--3.75*dir((1,3))^^O--3.75*dir((1,k))); | ||

| + | </asy> | ||

| + | ~MRENTHUSIASM | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 1 (Angle Bisector Theorem)== | ||

| + | This solution refers to the <b>Diagram</b> section. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Let <math>O=(0,0), A=(3,3), B=(1,3),</math> and <math>C=\left(\frac3k,3\right).</math> As shown below, note that <math>\overline{OA}, \overline{OB},</math> and <math>\overline{OC}</math> are on the lines <math>y=x, y=3x,</math> and <math>y=kx,</math> respectively. By the Distance Formula, we have <math>OA=3\sqrt2, OB=\sqrt{10}, AC=3-\frac3k,</math> and <math>BC=\frac3k-1.</math> | ||

| + | <asy> | ||

| + | /* Made by MRENTHUSIASM */ | ||

| + | size(250); | ||

| + | |||

| + | real xMin = -1; | ||

| + | real xMax = 4; | ||

| + | real yMin = -1; | ||

| + | real yMax = 4; | ||

| + | real k = (1+sqrt(5))/2; | ||

| + | |||

| + | pair O, A, B, C; | ||

| + | O = origin; | ||

| + | A = (3,3); | ||

| + | B = (1,3); | ||

| + | C = (3/k,3); | ||

| + | |||

| + | draw(anglemark(dir((1,1)),O,dir((1,k)),20), red); | ||

| + | draw(anglemark(dir((1,k)),O,dir((1,3)),20), red); | ||

| + | |||

| + | dot("$O$",O,1.5*SW,linewidth(4.5)); | ||

| + | dot("$A$",A,1.5*N,linewidth(4.5)); | ||

| + | dot("$B$",B,1.5*N,linewidth(4.5)); | ||

| + | dot("$C$",C,1.5*N,linewidth(4.5)); | ||

| + | |||

| + | add(pathticks(anglemark(dir((1,1)),O,dir((1,k)),20), n = 1, r = 0.05, s = 5, red)); | ||

| + | add(pathticks(anglemark(dir((1,k)),O,dir((1,3)),20), n = 1, r = 0.05, s = 5, red)); | ||

| + | draw((xMin,0)--(xMax,0),black+linewidth(1.5),EndArrow(5)); | ||

| + | draw((0,yMin)--(0,yMax),black+linewidth(1.5),EndArrow(5)); | ||

| + | draw(A--B--O--cycle^^O--C); | ||

| + | |||

| + | label("$x$",(xMax,0),(2,0)); | ||

| + | label("$y$",(0,yMax),(0,2)); | ||

| + | label("$3\sqrt{2}$",midpoint(O--A),1.5*E,red+fontsize(10)); | ||

| + | label("$\sqrt{10}$",midpoint(O--B),W,red+fontsize(10)); | ||

| + | label("$3-\frac3k$",midpoint(A--C),N,red+fontsize(10)); | ||

| + | label("$\frac3k-1$",midpoint(B--C),N,red+fontsize(10)); | ||

| + | </asy> | ||

| + | By the Angle Bisector Theorem, we get <math>\frac{OA}{OB}=\frac{AC}{BC},</math> or | ||

<cmath>\begin{align*} | <cmath>\begin{align*} | ||

\frac{3\sqrt2}{\sqrt{10}}&=\frac{3-\frac3k}{\frac3k-1} \\ | \frac{3\sqrt2}{\sqrt{10}}&=\frac{3-\frac3k}{\frac3k-1} \\ | ||

| Line 23: | Line 87: | ||

\end{align*}</cmath> | \end{align*}</cmath> | ||

Since <math>k>0,</math> the answer is <math>k=\boxed{\textbf{(A)} \ \frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}}.</math> | Since <math>k>0,</math> the answer is <math>k=\boxed{\textbf{(A)} \ \frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}}.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <u><b>Remark</b></u> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The value of <math>k</math> is known as the <b>Golden Ratio</b>: <math>\phi=\frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}\approx 1.61803398875.</math> | ||

~MRENTHUSIASM | ~MRENTHUSIASM | ||

| − | ==Solution 2== | + | ==Solution 2 (Analytic and Plane Geometry) == |

| + | <asy> | ||

| + | size(180); | ||

| + | |||

| + | real xMin = -0.5; | ||

| + | real xMax = 2; | ||

| + | real yMin = -0.5; | ||

| + | real yMax = 4.5; | ||

| + | real k = (1+sqrt(5))/2; | ||

| + | real m = sqrt(2); | ||

| + | real n = sqrt(10); | ||

| + | real q = sqrt((5+sqrt(5))/2); | ||

| + | |||

| + | pair O; | ||

| + | O = origin; | ||

| + | |||

| + | draw((xMin,0)--(xMax,0),black+linewidth(1.5),EndArrow(5)); | ||

| + | draw((0,yMin)--(0,yMax),black+linewidth(1.5),EndArrow(5)); | ||

| + | label("$O$",(-0.2,-0.2),(0,0)); | ||

| + | label("$x$",(xMax,0),(2,0)); | ||

| + | label("$y$",(0,yMax),(0,2)); | ||

| + | label("$A$",(1,0.95),(1,1)); | ||

| + | label("$B$",(1,2.80),(1,3)); | ||

| + | label("$C$",(1.06,k-0.05),(1,k)); | ||

| + | |||

| + | draw(O--m*dir((1,1))^^O--n*dir((1,3))^^O--q*dir((1,k))); | ||

| + | draw((1,1)--(1,3)); | ||

| + | </asy> | ||

| + | Consider the graphs of <math>f(x)=x</math> and <math>g(x)=3x</math>. Since it will be easier to consider at unity, let <math>x=1</math>, then we have <math>f(1)=1</math> and <math>g(1)=3</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Now, let <math>O</math> be <math>(0,0)</math>, <math>A</math> be <math>(1,1)</math>, and <math>B</math> be <math>(1,3)</math>. Cutting through side <math>AB</math> of triangle <math>OAB</math> is the angle bisector <math>OC</math> where <math>C</math> is on side <math>AB</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hence, by the Angle Bisector Theorem, we get <math>\frac{OB}{OA}=\frac{BC}{AC}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | By the Pythagorean Theorem, <math>OA=\sqrt{2}</math> and <math>OB=\sqrt{10}</math>. Therefore, <math>\frac{BC}{AC}=\sqrt{5} \implies BC=\sqrt{5}AC</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Since <math>AB=AC+BC=2</math>, it is easy derive <math>AC+\sqrt{5}AC=2 \implies AC=\frac{2}{1+\sqrt{5}}=\frac{-1+\sqrt{5}}{2}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The vertical distance between the <math>x</math>-axis and <math>C</math> is <math>\frac{-1+\sqrt{5}}{2}+1=\frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}</math>. Because the <math>x</math>-coordinate of point <math>C</math> is <math>1</math>, the slope we need to find is just the <math>y</math>-coordinate <math>\boxed{\textbf{(A)} \ \frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}}.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ~Wilhelm Z | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 3 (Analytic and Plane Geometry)== | ||

| + | Let's begin by drawing a triangle that starts at the origin. Assume that the base of the triangle goes to the point <math>x = 1</math>. The line <math>x = y</math> is the hypotenuse of a right triangle with side length <math>1</math>. The hypotenuse' length is <math>\sqrt 2</math>. Then, let's draw the line <math>x = 3y</math>. We extend it to when <math>x = 1</math>. The length of the hypotenuse of the larger triangle is <math>\sqrt {10}</math> with legs <math>1, 3</math>. We then draw the angle bisector. We should label the triangle, so here we go. <math>AC</math> is <math>1</math>. <math>BC</math> is <math>3</math>. <math>AB</math> is <math>\sqrt {10}</math>. When the line with angle <math>45 ^\circ</math> intersects the line <math>x = 1</math>, call the point <math>D</math>. When the angle bisector intersects the line <math>x = 1</math>, call the point <math>E</math>. By Angle Bisector Theorem, <math>\frac {DE}{DB} = \frac {\sqrt {2}}{\sqrt{10}}</math>. Since <math>BC</math> is <math>3</math> and <math>DC</math> is <math>1</math>, we have that <math>BD</math> is <math>2</math>. Solving for <math>DE</math>, we get that <math>DE</math> is <math>\frac {\sqrt 5 - 1}{2}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Since <math>DE</math> is <math>\frac {\sqrt 5 - 1}{2}</math>, we have that <math>CE</math> is just one more than that. Therefore, <math>CE</math> is <math>\frac {1+\sqrt 5}{2}</math>. Since <math>AC</math> is <math>1</math>, we get that <math>k</math> is <math>\boxed{\textbf{(A)} \ \frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <u><b>Remark</b></u> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The answer turns out to be the golden ratio or phi (<math>\phi</math>). Phi has many properties and is related to the [[Fibonacci sequence]]. See [[Phi]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ~Arcticturn <math>\blacksquare</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 4 (Distance Between a Point and a Line)== | ||

Note that the distance between the point <math>(m,n)</math> to line <math>Ax + By + C = 0,</math> is <math>\frac{|Am + Bn +C|}{\sqrt{A^2 +B^2}}.</math> Because line <math>y=kx</math> is a perpendicular bisector, a point on the line <math>y=kx</math> must be equidistant from the two lines(<math>y=x</math> and <math>y=3x</math>), call this point <math>P(z,w).</math> Because, the line <math>y=kx</math> passes through the origin, our requested value of <math>k,</math> which is the slope of the angle bisector line, can be found when evaluating the value of <math>\frac{w}{z}.</math> By the Distance from Point to Line formula we get the equation, <cmath>\frac{|3z-w|}{\sqrt{10}} = \frac{|z-w|}{\sqrt{2}}.</cmath> Note that <math>|3z-w|\ge 0,</math> because <math>y=3x</math> is higher than <math>P</math> and <math>|z-w|\le 0,</math> because <math>y=x</math> is lower to <math>P.</math> Thus, we solve the equation, <cmath>(3z-w)\sqrt{2} = (w-z)\sqrt{10} \Rightarrow 3z-w = \sqrt{5} \cdot(w-z)\Rightarrow (\sqrt{5} +1)w = (3+\sqrt{5})z.</cmath> Thus, the value of <math>\frac{w}{z} = \frac{3+\sqrt{5}}{1+\sqrt{5}} = \frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}.</math> Thus, the answer is <math>\boxed{\textbf{(A)} \ \frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}}.</math> | Note that the distance between the point <math>(m,n)</math> to line <math>Ax + By + C = 0,</math> is <math>\frac{|Am + Bn +C|}{\sqrt{A^2 +B^2}}.</math> Because line <math>y=kx</math> is a perpendicular bisector, a point on the line <math>y=kx</math> must be equidistant from the two lines(<math>y=x</math> and <math>y=3x</math>), call this point <math>P(z,w).</math> Because, the line <math>y=kx</math> passes through the origin, our requested value of <math>k,</math> which is the slope of the angle bisector line, can be found when evaluating the value of <math>\frac{w}{z}.</math> By the Distance from Point to Line formula we get the equation, <cmath>\frac{|3z-w|}{\sqrt{10}} = \frac{|z-w|}{\sqrt{2}}.</cmath> Note that <math>|3z-w|\ge 0,</math> because <math>y=3x</math> is higher than <math>P</math> and <math>|z-w|\le 0,</math> because <math>y=x</math> is lower to <math>P.</math> Thus, we solve the equation, <cmath>(3z-w)\sqrt{2} = (w-z)\sqrt{10} \Rightarrow 3z-w = \sqrt{5} \cdot(w-z)\Rightarrow (\sqrt{5} +1)w = (3+\sqrt{5})z.</cmath> Thus, the value of <math>\frac{w}{z} = \frac{3+\sqrt{5}}{1+\sqrt{5}} = \frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}.</math> Thus, the answer is <math>\boxed{\textbf{(A)} \ \frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}}.</math> | ||

| Line 33: | Line 154: | ||

~NH14 | ~NH14 | ||

| − | ==Solution 3 ( | + | == Solution 5 (Trigonometry) == |

| − | + | ||

| + | This problem can be trivialized using basic trig identities. Let the angle made by <math>y=x</math> and the <math>x</math>-axis be <math>\theta_{1}</math> and the angle made by <math>y=3x</math> and the <math>x</math>-axis be <math>\theta_{3}</math>. Note that <math>\tan(\theta_{1})=1</math> and <math>\tan(\theta_{3})=3</math>, and this is why we named them as such. Let the angle made by <math>y=kx</math> be denoted as <math>\theta_{k}</math>. Since <math>y=kx</math> bisects the two lines, notice that | ||

| + | <cmath>\theta_k-\theta_1=\theta_3-\theta_k.</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Now, we can take the tangent and apply the tangent subtraction formula: | ||

| + | <cmath> | ||

| + | \begin{align*} | ||

| + | \tan(\theta_k-\theta_1)&=\tan(\theta_3-\theta_k)\\ | ||

| + | \frac{\tan(\theta_k)-\tan(\theta_1)}{1+\tan(\theta_k)\tan(\theta_1)}&=\frac{\tan(\theta_3)-\tan(\theta_k)}{1+\tan(\theta_3)\tan(\theta_k)}\\ | ||

| + | \frac{k-1}{1+k}&=\frac{3-k}{1+3k}\\ | ||

| + | (k-1)(1+3k)&=(1+k)(3-k)\\ | ||

| + | 3k^2-2k-1&=-k^2+2k+3\\ | ||

| + | 4k^2-4k-4&=0\\ | ||

| + | k^2-k-1&=0\\ | ||

| + | \implies k&=\frac{1\pm \sqrt{5}}{2} | ||

| + | \end{align*} | ||

| + | </cmath> | ||

| + | Since <math>y=kx</math> is increasing, <math>k>0</math>; thus, <math>k=\boxed{\textbf{(A)} \ \frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}}.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ~Indiiiigo | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Solution 6 (Trigonometry) == | ||

| + | Denote by <math>\alpha_1</math>, <math>\alpha_2</math>, <math>\alpha_3</math> the acute angles formed between the <math>x</math>-axis and lines <math>y = x</math>, <math>y = 3 x</math>, <math>y = k x</math>, respectively. | ||

| + | Hence, <math>\tan \alpha_1 = 1</math>, <math>\tan \alpha_2 = 3</math>, <math>\tan \alpha_3 = k</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Denote by <math>\theta</math> the acute angle formed by lines <math>y = x</math> and <math>y = 3 x</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hence, | ||

| + | <cmath> | ||

| + | \begin{align*} | ||

| + | \tan \theta & = \tan \left( \alpha_2 - \alpha_1 \right) \\ | ||

| + | & = \frac{\tan \alpha_2 - \tan \alpha_1}{1 + \tan \alpha_1 \tan \alpha_2} \\ | ||

| + | &= \frac{3 - 1}{1 + 1 \cdot 3} \\ | ||

| + | & = \frac{1}{2} . | ||

| + | \end{align*} | ||

| + | </cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Following from the double-angle identity, we have | ||

| + | <cmath> | ||

| + | \[ | ||

| + | \tan \theta = \frac{2 \tan \frac{\theta}{2}}{1 - \tan^2 \frac{\theta}{2}} . | ||

| + | \] | ||

| + | </cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hence, <math>\tan \frac{\theta}{2} = - 2 \pm \sqrt{5}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Because <math>\theta</math> is acute, <math>\frac{\theta}{2}</math> is acute. | ||

| + | Hence, <math>\tan \frac{\theta}{2} > 0</math>. | ||

| + | Hence, <math>\tan \frac{\theta}{2} = - 2 + \sqrt{5}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Because line <math>y = kx</math> is the angle bisector of <math>\theta</math>, the angle between lines <math>y = x</math> and <math>y = k x</math> is <math>\frac{\theta}{2}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hence, | ||

| + | <cmath> | ||

| + | \begin{align*} | ||

| + | \tan \alpha_3 & = \tan \left( \alpha_1 + \frac{\theta}{2} \right) \\ | ||

| + | & = \frac{\tan \alpha_1 + \tan \frac{\theta}{2}}{1 - \tan \alpha_1 \tan \frac{\theta}{2}} \\ | ||

| + | &= \frac{1 + \left( - 2 + \sqrt{5} \right)}{1 - 1 \cdot \left( - 2 + \sqrt{5} \right) } \\ | ||

| + | & = \frac{\sqrt{5} - 1}{3 - \sqrt{5}} \\ | ||

| + | & = \frac{1 + \sqrt{5}}{2} . | ||

| + | \end{align*} | ||

| + | </cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Therefore, the answer is <math>\boxed{\textbf{(A) }\frac{1 + \sqrt{5}}{2}}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ~Steven Chen (www.professorchenedu.com) | ||

| + | |||

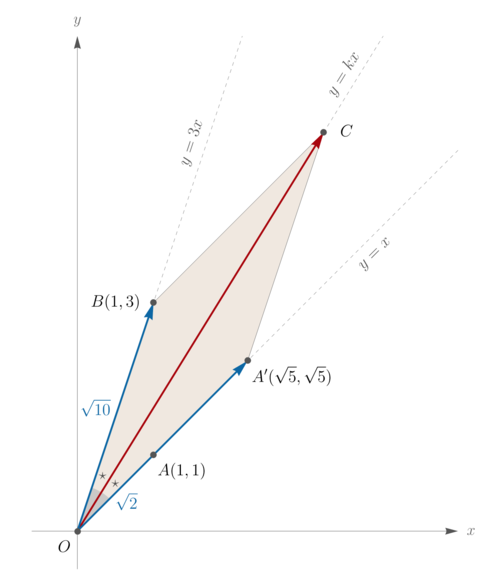

| + | == Solution 7 (Vectors) == | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:2021FallAMC12AProblem13.png|center|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | When drawing the lines <math>y=x</math> and <math>y=3x</math>, it is natural to choose points <math>A(1,1)</math> and <math>B(1,3)</math> together with origin <math>O</math>. See the figure attached. | ||

| + | We utilize the fact that if <math>\mathbf{u}</math> and <math>\mathbf{v}</math> are vectors of same length, then <math>\mathbf{u} + \mathbf{v}</math> bisects the angle between <math>\mathbf{u}</math> and <math>\mathbf{v}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In particular, we scale the vector <math>\overrightarrow{OA} = (1,1)</math> by the factor of <math>\frac{OB}{OA} = \frac{\sqrt{10}}{\sqrt{2}} = \sqrt{5}</math> to get <math> \overrightarrow{OA'} \coloneqq \sqrt{5}\,\overrightarrow{OA} = \left(\sqrt{5}, \sqrt{5}\right)</math>. | ||

| + | So by adding vectors <math>\overrightarrow{OA'}</math> and <math>\overrightarrow{OB} = (1,3)</math> we get | ||

| + | <cmath> | ||

| + | {\color[rgb]{0.666667,0,0}\overrightarrow{OC}} | ||

| + | \coloneqq {\color[rgb]{0,0.4,0.65}\overrightarrow{OA'}} + {\color[rgb]{0,0.4,0.65}\overrightarrow{OB}} | ||

| + | = \left( 1 + \sqrt{5}, 3 + \sqrt{5} \right) | ||

| + | </cmath> | ||

| + | which bisects the acute angle formed by lines <math>OA: y = x</math> and <math>OB: y = 3x</math>. (In other words, quadrilateral <math>OBCA'</math> is a rhombus.) | ||

| + | Finally, observe that <math>C\!\left(1+\sqrt{5}, 3+\sqrt{5}\right)</math> lies on the line <math>y = kx</math> whose slope is | ||

| + | <cmath> | ||

| + | k = \frac{3+\sqrt{5}}{1+\sqrt{5}} = \frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}. | ||

| + | </cmath> | ||

| + | Thus, the answer is <math>\boxed{\textbf{(A)}\;\frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}}</math>. <math>\blacksquare</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ~VensL. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Solution 8 (Dot Product) == | ||

| + | |||

| + | We notice that the line <math>y = x</math> can be represented as the vector <math>\vec{A} = \begin{bmatrix} | ||

| + | 1 \\ 1 | ||

| + | \end{bmatrix}</math> | ||

| + | and <math>y = 3x</math> as <math>\vec{B} = \begin{bmatrix} | ||

| + | 1 \\ 3 | ||

| + | \end{bmatrix}</math> | ||

| + | as the "slope" of both vectors represent the coefficient of <math>x</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Then, we can represent <math>y = kx</math> as <math>\vec{C} = \begin{bmatrix} | ||

| + | 1 \\ k | ||

| + | \end{bmatrix}</math> and notice that since <math>C</math> is in essence an angle bisector, <cmath>\theta = \angle \vec{A}\vec{C} = \angle \vec{B}\vec{C}</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <cmath>A \cdot C = |A|\cdot|C|\cos(\theta_1)</cmath> where <math>\theta_1 = \angle \vec{A}\vec{C} = \theta</math> | ||

| + | <cmath>B \cdot C = |B|\cdot|C|\cos(\theta_2)</cmath> where <math>\theta_2 = \angle \vec{B}\vec{C} = \theta</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Since both <math>\theta_i</math>'s are equivalent, we may simply represent them with <math>\theta</math>. | ||

| − | + | Simplifying both equations by performing the necessary operations, we get | |

| − | + | <cmath>1+k = \sqrt{2} \cdot \sqrt{k^2 + 1} \cdot \cos(\theta) \implies \frac{1+k}{\sqrt{2}} = \sqrt{k^2 + 1} \cos(\theta)</cmath> | |

| − | + | <cmath>1+3k = \sqrt{10} \cdot \sqrt{k^2 + 1} \cdot \cos(\theta)</cmath> | |

| − | + | Substituting the first into the second, we get | |

| + | <cmath>1 + 3k = \sqrt{10} \cdot \frac{1+k}{\sqrt{2}} \implies k=\boxed{\textbf{(A)} \ \frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}}</cmath> | ||

| − | + | ~ <math>\color{magenta} zoomanTV</math> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Video Solution by TheBeautyofMath== | |

| + | https://youtu.be/ToiOlqWz3LY?t=504 | ||

| + | ~IceMatrix | ||

==See Also== | ==See Also== | ||

{{AMC12 box|year=2021 Fall|ab=A|num-b=12|num-a=14}} | {{AMC12 box|year=2021 Fall|ab=A|num-b=12|num-a=14}} | ||

{{MAA Notice}} | {{MAA Notice}} | ||

Latest revision as of 13:27, 1 September 2024

Contents

- 1 Problem

- 2 Diagram

- 3 Solution 1 (Angle Bisector Theorem)

- 4 Solution 2 (Analytic and Plane Geometry)

- 5 Solution 3 (Analytic and Plane Geometry)

- 6 Solution 4 (Distance Between a Point and a Line)

- 7 Solution 5 (Trigonometry)

- 8 Solution 6 (Trigonometry)

- 9 Solution 7 (Vectors)

- 10 Solution 8 (Dot Product)

- 11 Video Solution by TheBeautyofMath

- 12 See Also

Problem

The angle bisector of the acute angle formed at the origin by the graphs of the lines ![]() and

and ![]() has equation

has equation ![]() What is

What is ![]()

![]()

Diagram

![[asy] /* Made by MRENTHUSIASM */ size(250); real xMin = -1; real xMax = 4; real yMin = -1; real yMax = 4; real k = (1+sqrt(5))/2; pair O; O = origin; draw(anglemark(dir((1,1)),O,dir((1,k)),20), red); draw(anglemark(dir((1,k)),O,dir((1,3)),20), red); add(pathticks(anglemark(dir((1,1)),O,dir((1,k)),20), n = 1, r = 0.05, s = 5, red)); add(pathticks(anglemark(dir((1,k)),O,dir((1,3)),20), n = 1, r = 0.05, s = 5, red)); draw((xMin,0)--(xMax,0),black+linewidth(1.5),EndArrow(5)); draw((0,yMin)--(0,yMax),black+linewidth(1.5),EndArrow(5)); label("$x$",(xMax,0),(2,0)); label("$y$",(0,yMax),(0,2)); label("$y=x$",4*dir((1,1))); label("$y=3x$",4*dir((1,3))); label("$y=kx$",4*dir((1,k))); draw(O--3.75*dir((1,1))^^O--3.75*dir((1,3))^^O--3.75*dir((1,k))); [/asy]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/e/d/8/ed8c030315c6a7a32e49ccbd13eeb76fd3d85b39.png) ~MRENTHUSIASM

~MRENTHUSIASM

Solution 1 (Angle Bisector Theorem)

This solution refers to the Diagram section.

Let ![]() and

and ![]() As shown below, note that

As shown below, note that ![]() and

and ![]() are on the lines

are on the lines ![]() and

and ![]() respectively. By the Distance Formula, we have

respectively. By the Distance Formula, we have ![]() and

and ![]()

![[asy] /* Made by MRENTHUSIASM */ size(250); real xMin = -1; real xMax = 4; real yMin = -1; real yMax = 4; real k = (1+sqrt(5))/2; pair O, A, B, C; O = origin; A = (3,3); B = (1,3); C = (3/k,3); draw(anglemark(dir((1,1)),O,dir((1,k)),20), red); draw(anglemark(dir((1,k)),O,dir((1,3)),20), red); dot("$O$",O,1.5*SW,linewidth(4.5)); dot("$A$",A,1.5*N,linewidth(4.5)); dot("$B$",B,1.5*N,linewidth(4.5)); dot("$C$",C,1.5*N,linewidth(4.5)); add(pathticks(anglemark(dir((1,1)),O,dir((1,k)),20), n = 1, r = 0.05, s = 5, red)); add(pathticks(anglemark(dir((1,k)),O,dir((1,3)),20), n = 1, r = 0.05, s = 5, red)); draw((xMin,0)--(xMax,0),black+linewidth(1.5),EndArrow(5)); draw((0,yMin)--(0,yMax),black+linewidth(1.5),EndArrow(5)); draw(A--B--O--cycle^^O--C); label("$x$",(xMax,0),(2,0)); label("$y$",(0,yMax),(0,2)); label("$3\sqrt{2}$",midpoint(O--A),1.5*E,red+fontsize(10)); label("$\sqrt{10}$",midpoint(O--B),W,red+fontsize(10)); label("$3-\frac3k$",midpoint(A--C),N,red+fontsize(10)); label("$\frac3k-1$",midpoint(B--C),N,red+fontsize(10)); [/asy]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/8/2/b/82be28b0a53989856283345e955461652bcb3a42.png) By the Angle Bisector Theorem, we get

By the Angle Bisector Theorem, we get ![]() or

or

Since

Since ![]() the answer is

the answer is

Remark

The value of ![]() is known as the Golden Ratio:

is known as the Golden Ratio: ![]()

~MRENTHUSIASM

Solution 2 (Analytic and Plane Geometry)

![[asy] size(180); real xMin = -0.5; real xMax = 2; real yMin = -0.5; real yMax = 4.5; real k = (1+sqrt(5))/2; real m = sqrt(2); real n = sqrt(10); real q = sqrt((5+sqrt(5))/2); pair O; O = origin; draw((xMin,0)--(xMax,0),black+linewidth(1.5),EndArrow(5)); draw((0,yMin)--(0,yMax),black+linewidth(1.5),EndArrow(5)); label("$O$",(-0.2,-0.2),(0,0)); label("$x$",(xMax,0),(2,0)); label("$y$",(0,yMax),(0,2)); label("$A$",(1,0.95),(1,1)); label("$B$",(1,2.80),(1,3)); label("$C$",(1.06,k-0.05),(1,k)); draw(O--m*dir((1,1))^^O--n*dir((1,3))^^O--q*dir((1,k))); draw((1,1)--(1,3)); [/asy]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/a/7/0/a704fe951a038435a7c1011a84366eecaea2521c.png) Consider the graphs of

Consider the graphs of ![]() and

and ![]() . Since it will be easier to consider at unity, let

. Since it will be easier to consider at unity, let ![]() , then we have

, then we have ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Now, let ![]() be

be ![]() ,

, ![]() be

be ![]() , and

, and ![]() be

be ![]() . Cutting through side

. Cutting through side ![]() of triangle

of triangle ![]() is the angle bisector

is the angle bisector ![]() where

where ![]() is on side

is on side ![]() .

.

Hence, by the Angle Bisector Theorem, we get ![]() .

.

By the Pythagorean Theorem, ![]() and

and ![]() . Therefore,

. Therefore, ![]() .

.

Since ![]() , it is easy derive

, it is easy derive ![]() .

.

The vertical distance between the ![]() -axis and

-axis and ![]() is

is ![]() . Because the

. Because the ![]() -coordinate of point

-coordinate of point ![]() is

is ![]() , the slope we need to find is just the

, the slope we need to find is just the ![]() -coordinate

-coordinate

~Wilhelm Z

Solution 3 (Analytic and Plane Geometry)

Let's begin by drawing a triangle that starts at the origin. Assume that the base of the triangle goes to the point ![]() . The line

. The line ![]() is the hypotenuse of a right triangle with side length

is the hypotenuse of a right triangle with side length ![]() . The hypotenuse' length is

. The hypotenuse' length is ![]() . Then, let's draw the line

. Then, let's draw the line ![]() . We extend it to when

. We extend it to when ![]() . The length of the hypotenuse of the larger triangle is

. The length of the hypotenuse of the larger triangle is ![]() with legs

with legs ![]() . We then draw the angle bisector. We should label the triangle, so here we go.

. We then draw the angle bisector. We should label the triangle, so here we go. ![]() is

is ![]() .

. ![]() is

is ![]() .

. ![]() is

is ![]() . When the line with angle

. When the line with angle ![]() intersects the line

intersects the line ![]() , call the point

, call the point ![]() . When the angle bisector intersects the line

. When the angle bisector intersects the line ![]() , call the point

, call the point ![]() . By Angle Bisector Theorem,

. By Angle Bisector Theorem, ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() is

is ![]() and

and ![]() is

is ![]() , we have that

, we have that ![]() is

is ![]() . Solving for

. Solving for ![]() , we get that

, we get that ![]() is

is ![]() .

.

Since ![]() is

is ![]() , we have that

, we have that ![]() is just one more than that. Therefore,

is just one more than that. Therefore, ![]() is

is ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() is

is ![]() , we get that

, we get that ![]() is

is  .

.

Remark

The answer turns out to be the golden ratio or phi (![]() ). Phi has many properties and is related to the Fibonacci sequence. See Phi.

). Phi has many properties and is related to the Fibonacci sequence. See Phi.

~Arcticturn ![]()

Solution 4 (Distance Between a Point and a Line)

Note that the distance between the point ![]() to line

to line ![]() is

is ![]() Because line

Because line ![]() is a perpendicular bisector, a point on the line

is a perpendicular bisector, a point on the line ![]() must be equidistant from the two lines(

must be equidistant from the two lines(![]() and

and ![]() ), call this point

), call this point ![]() Because, the line

Because, the line ![]() passes through the origin, our requested value of

passes through the origin, our requested value of ![]() which is the slope of the angle bisector line, can be found when evaluating the value of

which is the slope of the angle bisector line, can be found when evaluating the value of ![]() By the Distance from Point to Line formula we get the equation,

By the Distance from Point to Line formula we get the equation, ![]() Note that

Note that ![]() because

because ![]() is higher than

is higher than ![]() and

and ![]() because

because ![]() is lower to

is lower to ![]() Thus, we solve the equation,

Thus, we solve the equation, ![]() Thus, the value of

Thus, the value of ![]() Thus, the answer is

Thus, the answer is

(Fun Fact: The value ![]() is the golden ratio

is the golden ratio ![]() )

)

~NH14

Solution 5 (Trigonometry)

This problem can be trivialized using basic trig identities. Let the angle made by ![]() and the

and the ![]() -axis be

-axis be ![]() and the angle made by

and the angle made by ![]() and the

and the ![]() -axis be

-axis be ![]() . Note that

. Note that ![]() and

and ![]() , and this is why we named them as such. Let the angle made by

, and this is why we named them as such. Let the angle made by ![]() be denoted as

be denoted as ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() bisects the two lines, notice that

bisects the two lines, notice that

![]()

Now, we can take the tangent and apply the tangent subtraction formula:

Since

Since ![]() is increasing,

is increasing, ![]() ; thus,

; thus,

~Indiiiigo

Solution 6 (Trigonometry)

Denote by ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() the acute angles formed between the

the acute angles formed between the ![]() -axis and lines

-axis and lines ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , respectively.

Hence,

, respectively.

Hence, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() .

.

Denote by ![]() the acute angle formed by lines

the acute angle formed by lines ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Hence,

Following from the double-angle identity, we have

![]()

Hence, ![]() .

.

Because ![]() is acute,

is acute, ![]() is acute.

Hence,

is acute.

Hence, ![]() .

Hence,

.

Hence, ![]() .

.

Because line ![]() is the angle bisector of

is the angle bisector of ![]() , the angle between lines

, the angle between lines ![]() and

and ![]() is

is ![]() .

.

Hence,

Therefore, the answer is  .

.

~Steven Chen (www.professorchenedu.com)

Solution 7 (Vectors)

When drawing the lines ![]() and

and ![]() , it is natural to choose points

, it is natural to choose points ![]() and

and ![]() together with origin

together with origin ![]() . See the figure attached.

We utilize the fact that if

. See the figure attached.

We utilize the fact that if ![]() and

and ![]() are vectors of same length, then

are vectors of same length, then ![]() bisects the angle between

bisects the angle between ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

In particular, we scale the vector ![]() by the factor of

by the factor of ![]() to get

to get ![]() .

So by adding vectors

.

So by adding vectors ![]() and

and ![]() we get

we get

![]() which bisects the acute angle formed by lines

which bisects the acute angle formed by lines ![]() and

and ![]() . (In other words, quadrilateral

. (In other words, quadrilateral ![]() is a rhombus.)

Finally, observe that

is a rhombus.)

Finally, observe that ![]() lies on the line

lies on the line ![]() whose slope is

whose slope is

![]() Thus, the answer is

Thus, the answer is  .

. ![]()

~VensL.

Solution 8 (Dot Product)

We notice that the line ![]() can be represented as the vector

can be represented as the vector ![]() and

and ![]() as

as ![]() as the "slope" of both vectors represent the coefficient of

as the "slope" of both vectors represent the coefficient of ![]() .

.

Then, we can represent ![]() as

as ![]() and notice that since

and notice that since ![]() is in essence an angle bisector,

is in essence an angle bisector, ![]()

![]() where

where ![]()

![]() where

where ![]()

Since both ![]() 's are equivalent, we may simply represent them with

's are equivalent, we may simply represent them with ![]() .

.

Simplifying both equations by performing the necessary operations, we get

![]()

![]()

Substituting the first into the second, we get

![\[1 + 3k = \sqrt{10} \cdot \frac{1+k}{\sqrt{2}} \implies k=\boxed{\textbf{(A)} \ \frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}}\]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/f/2/7/f27ebf0d94477b3ef8619738d5c016593b0e42c2.png)

~ ![]()

Video Solution by TheBeautyofMath

https://youtu.be/ToiOlqWz3LY?t=504

~IceMatrix

See Also

| 2021 Fall AMC 12A (Problems • Answer Key • Resources) | |

| Preceded by Problem 12 |

Followed by Problem 14 |

| 1 • 2 • 3 • 4 • 5 • 6 • 7 • 8 • 9 • 10 • 11 • 12 • 13 • 14 • 15 • 16 • 17 • 18 • 19 • 20 • 21 • 22 • 23 • 24 • 25 | |

| All AMC 12 Problems and Solutions | |

The problems on this page are copyrighted by the Mathematical Association of America's American Mathematics Competitions.