Difference between revisions of "1989 AIME Problems/Problem 15"

(→Solution 5(Mass of a point+ Stewart+heron)) |

(→Solution 2 (Mass Points, Stewart's Theorem, Heron's Formula)) |

||

| (31 intermediate revisions by 10 users not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

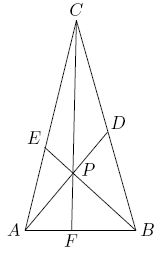

[[Image:AIME_1989_Problem_15.png|center]] | [[Image:AIME_1989_Problem_15.png|center]] | ||

| − | == Solution == | + | == Solutions == |

| − | === Solution | + | |

| + | === Solution 1 (Ceva's Theorem, Stewart's Theorem) === | ||

| + | |||

| + | Let <math>[RST]</math> be the area of polygon <math>RST</math>. We'll make use of the following fact: if <math>P</math> is a point in the interior of triangle <math>XYZ</math>, and line <math>XP</math> intersects line <math>YZ</math> at point <math>L</math>, then <math>\dfrac{XP}{PL} = \frac{[XPY] + [ZPX]}{[YPZ]}.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <center><asy> | ||

| + | size(170); | ||

| + | pair X = (1,2), Y = (0,0), Z = (3,0); | ||

| + | real x = 0.4, y = 0.2, z = 1-x-y; | ||

| + | pair P = x*X + y*Y + z*Z; | ||

| + | pair L = y/(y+z)*Y + z/(y+z)*Z; | ||

| + | draw(X--Y--Z--cycle); | ||

| + | draw(X--P); | ||

| + | draw(P--L, dotted); | ||

| + | draw(Y--P--Z); | ||

| + | label("$X$", X, N); | ||

| + | label("$Y$", Y, S); | ||

| + | label("$Z$", Z, S); | ||

| + | label("$P$", P, NE); | ||

| + | label("$L$", L, S);</asy></center> | ||

| + | |||

| + | This is true because triangles <math>XPY</math> and <math>YPL</math> have their areas in ratio <math>XP:PL</math> (as they share a common height from <math>Y</math>), and the same is true of triangles <math>ZPY</math> and <math>LPZ</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | We'll also use the related fact that <math>\dfrac{[XPY]}{[ZPX]} = \dfrac{YL}{LZ}</math>. This is slightly more well known, as it is used in the standard proof of [[Ceva's theorem]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Now we'll apply these results to the problem at hand. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <center><asy> | ||

| + | size(170); | ||

| + | pair C = (1, 3), A = (0,0), B = (1.7,0); | ||

| + | real a = 0.5, b= 0.25, c = 0.25; | ||

| + | pair P = a*A + b*B + c*C; | ||

| + | pair D = b/(b+c)*B + c/(b+c)*C; | ||

| + | pair EE = c/(c+a)*C + a/(c+a)*A; | ||

| + | pair F = a/(a+b)*A + b/(a+b)*B; | ||

| + | draw(A--B--C--cycle); | ||

| + | draw(A--P); | ||

| + | draw(B--P--C); | ||

| + | draw(P--D, dotted); | ||

| + | draw(EE--P--F, dotted); | ||

| + | label("$A$", A, S); | ||

| + | label("$B$", B, S); | ||

| + | label("$C$", C, N); | ||

| + | label("$D$", D, NE); | ||

| + | label("$E$", EE, NW); | ||

| + | label("$F$", F, S); | ||

| + | label("$P$", P, E); | ||

| + | </asy></center> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Since <math>AP = PD = 6</math>, this means that <math>[APB] + [APC] = [BPC]</math>; thus <math>\triangle BPC</math> has half the area of <math>\triangle ABC</math>. And since <math>PE = 3 = \dfrac{1}{3}BP</math>, we can conclude that <math>\triangle APC</math> has one third of the combined areas of triangle <math>BPC</math> and <math>APB</math>, and thus <math>\dfrac{1}{4}</math> of the area of <math>\triangle ABC</math>. This means that <math>\triangle APB</math> is left with <math>\dfrac{1}{4}</math> of the area of triangle <math>ABC</math>: | ||

| + | <cmath> [BPC]: [APC]: [APB] = 2:1:1.</cmath> | ||

| + | Since <math>[APC] = [APB]</math>, and since <math>\dfrac{[APC]}{[APB]} = \dfrac{CD}{DB}</math>, this means that <math>D</math> is the midpoint of <math>BC</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Furthermore, we know that <math>\dfrac{CP}{PF} = \dfrac{[APC] + [BPC]}{[APB]} = 3</math>, so <math>CP = \dfrac{3}{4} \cdot CF = 15</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | We now apply [[Stewart's theorem]] to segment <math>PD</math> in <math>\triangle BPC</math>—or rather, the simplified version for a median. This tells us that | ||

| + | <cmath> 2 BD^2 + 2 PD^2 = BP^2+ CP^2. </cmath> Plugging in we know, we learn that | ||

| + | <cmath> \begin{align*} | ||

| + | 2 BD^2 + 2 \cdot 36 &= 81 + 225 = 306, \\ | ||

| + | BD^2 &= 117. \end{align*} </cmath> | ||

| + | Happily, <math>BP^2 + PD^2 = 81 + 36</math> is also equal to 117. Therefore <math>\triangle BPD</math> is a right triangle with a right angle at <math>B</math>; its area is thus <math>\dfrac{1}{2} \cdot 9 \cdot 6 = 27</math>. As <math>PD</math> is a median of <math>\triangle BPC</math>, the area of <math>BPC</math> is twice this, or 54. And we already know that <math>\triangle BPC</math> has half the area of <math>\triangle ABC</math>, which must therefore be <math>\boxed{108}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Solution 2 (Mass Points, Stewart's Theorem, Heron's Formula) === | ||

Because we're given three concurrent [[cevian]]s and their lengths, it seems very tempting to apply [[Mass points]]. We immediately see that <math>w_E = 3</math>, <math>w_B = 1</math>, and <math>w_A = w_D = 2</math>. Now, we recall that the masses on the three sides of the triangle must be balanced out, so <math>w_C = 1</math> and <math>w_F = 3</math>. Thus, <math>CP = 15</math> and <math>PF = 5</math>. | Because we're given three concurrent [[cevian]]s and their lengths, it seems very tempting to apply [[Mass points]]. We immediately see that <math>w_E = 3</math>, <math>w_B = 1</math>, and <math>w_A = w_D = 2</math>. Now, we recall that the masses on the three sides of the triangle must be balanced out, so <math>w_C = 1</math> and <math>w_F = 3</math>. Thus, <math>CP = 15</math> and <math>PF = 5</math>. | ||

| − | Recalling that <math>w_C = w_B = 1</math>, we see that <math>DC = DB</math> and <math>DP</math> is a [[median]] to <math>BC</math> in <math>\triangle BCP</math>. Applying [[Stewart's Theorem]], <math>BC^2 + | + | Recalling that <math>w_C = w_B = 1</math>, we see that <math>DC = DB</math> and <math>DP</math> is a [[median]] to <math>BC</math> in <math>\triangle BCP</math>. Applying [[Stewart's Theorem]], we have the following: |

| + | <cmath>\frac{BC}{2}(9^2+15^2)=BC(6^2+ \left(\frac{BC}{2} \right)^2).</cmath> | ||

| + | Eliminating <math>BC</math> on both sides, we have: | ||

| + | <cmath>\frac 12(9^2+15^2)=6^2+ \left(\frac{BC}{2} \right)^2.</cmath> | ||

| + | Combining terms and simplifying numbers, we have: | ||

| + | <cmath>153=36+\left(\frac{BC}{2} \right)^2.</cmath> | ||

| + | Subtracting 36 to the other side yields: | ||

| + | <cmath>117= \left(\frac{BC}{2} \right)^2.</cmath> | ||

| + | Finishing it off from there, we find that <math>BC=2 \sqrt{117}.</math> Now, notice that <math>2[BCP] = [ABC]</math>, because both triangles share the same base, <math>BC</math> and <math>h_{\triangle ABC} = 2h_{\triangle BCP}</math>. Applying [[Heron's formula]] on triangle <math>BCP</math> with sides <math>15</math>, <math>9</math>, and <math>2\sqrt{117}</math>, we have: | ||

| + | <cmath>\sqrt{(\sqrt{117}+12)(\sqrt{117}+12-9)(\sqrt{117}+12-15)(\sqrt{117}+12-2\sqrt{117})}.</cmath> | ||

| + | Combining terms results in: | ||

| + | <cmath>\sqrt{(\sqrt{117}+12)(\sqrt{117}+3)(\sqrt{117}-3)(-\sqrt{117}+12)}.</cmath> | ||

| + | Notice that these factors can be grouped into a difference of squares: | ||

| + | <cmath>\sqrt{(144-\sqrt{117}^2)(\sqrt{117}^2-9)}.</cmath> | ||

| + | Since <math>\sqrt{117}^2=117</math>, we have: | ||

| + | <cmath>\sqrt{(27)(108)}.</cmath> | ||

| + | After simplifying this radical, we find that it equals <math>54.</math> Therefore, <math>[BCP] = 54</math>, and hence <math>[ABC]=2 \cdot 54= \boxed{108}</math>. | ||

| − | === Solution | + | (The original author made a mistake in their solution. Corrected and further explained by dbnl.) |

| + | |||

| + | === Solution 3 (Ceva's Theorem, Stewart's Theorem) === | ||

Using a different form of [[Ceva's Theorem]], we have <math>\frac {y}{x + y} + \frac {6}{6 + 6} + \frac {3}{3 + 9} = 1\Longleftrightarrow\frac {y}{x + y} = \frac {1}{4}</math> | Using a different form of [[Ceva's Theorem]], we have <math>\frac {y}{x + y} + \frac {6}{6 + 6} + \frac {3}{3 + 9} = 1\Longleftrightarrow\frac {y}{x + y} = \frac {1}{4}</math> | ||

| Line 24: | Line 104: | ||

Using area ratio, <math>\triangle ABC = \triangle ADB\times 2 = \left(\triangle ADQ\times \frac32\right)\times 2 = 36\cdot 3 = \boxed{108}</math>. | Using area ratio, <math>\triangle ABC = \triangle ADB\times 2 = \left(\triangle ADQ\times \frac32\right)\times 2 = 36\cdot 3 = \boxed{108}</math>. | ||

| − | === Solution 3 === | + | === Solution 4 (Stewart's Theorem) === |

| − | + | ||

| + | First, let <math>[AEP]=a, [AFP]=b,</math> and <math>[ECP]=c.</math> Thus, we can easily find that <math>\frac{[AEP]}{[BPD]}=\frac{3}{9}=\frac{1}{3} \Leftrightarrow [BPD]=3[AEP]=3a.</math> Now, <math>\frac{[ABP]}{[BPD]}=\frac{6}{6}=1\Leftrightarrow [ABP]=3a.</math> In the same manner, we find that <math>[CPD]=a+c.</math> Now, we can find that <math>\frac{[BPC]}{[PEC]}=\frac{9}{3}=3 \Leftrightarrow \frac{(3a)+(a+c)}{c}=3 \Leftrightarrow c=2a.</math> We can now use this to find that <math>\frac{[APC]}{[AFP]}=\frac{[BPC]}{[BFP]}=\frac{PC}{FP} \Leftrightarrow \frac{3a}{b}=\frac{6a}{3a-b} \Leftrightarrow a=b.</math> Plugging this value in, we find that <math>\frac{FC}{FP}=3 \Leftrightarrow PC=15, FP=5.</math> Now, since <math>\frac{[AEP]}{[PEC]}=\frac{a}{2a}=\frac{1}{2},</math> we can find that <math>2AE=EC.</math> Setting <math>AC=b,</math> we can apply [[Stewart's Theorem]] on triangle <math>APC</math> to find that <math>(15)(15)(\frac{b}{3})+(6)(6)(\frac{2b}{3})=(\frac{2b}{3})(\frac{b}{3})(b)+(b)(3)(3).</math> Solving, we find that <math>b=\sqrt{405} \Leftrightarrow AE=\frac{b}{3}=\sqrt{45}.</math> But, <math>3^2+6^2=45,</math> meaning that <math>\angle{APE}=90 \Leftrightarrow [APE]=\frac{(6)(3)}{2}=9=a.</math> Since <math>[ABC]=a+a+2a+2a+3a+3a=12a=(12)(9)=108,</math> we conclude that the answer is <math>\boxed{108}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Solution 5 (Mass of a Point, Stewart's Theorem, Heron's Formula) === | ||

| + | Firstly, since they all meet at one single point, denoting the mass of them separately. Assuming <math>M(A)=6;M(D)=6;M(B)=3;M(E)=9</math>; we can get that <math>M(P)=12;M(F)=9;M(C)=3</math>; which leads to the ratio between segments, | ||

| + | <cmath>\frac{CE}{AE}=2;\frac{BF}{AF}=2;\frac{BD}{CD}=1.</cmath> Denoting that <math>CE=2x;AE=x; AF=y; BF=2y; CD=z; DB=z.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Now we know three cevians' length, Applying Stewart theorem to them, getting three different equations: | ||

| + | <cmath>\begin{align} | ||

| + | (3x)^2 \cdot 2y+(2z)^2 \cdot y&=(3y)(2y^2+400), \\ | ||

| + | (3y)^2 \cdot z+(3x)^2 \cdot z&=(2z)(z^2+144), \\ | ||

| + | (2z)^2 \cdot x+(3y)^2 \cdot x&=(3x)(2x^2+144). | ||

| + | \end{align}</cmath> | ||

| + | After solving the system of equation, we get that <math>x=3\sqrt{5};y=\sqrt{13};z=3\sqrt{13}</math>; | ||

| + | |||

| + | pulling <math>x,y,z</math> back to get the length of <math>AC=9\sqrt{5};AB=3\sqrt{13};BC=6\sqrt{13}</math>; now we can apply Heron's formula here, which is <cmath>\sqrt\frac{(9\sqrt{5}+9\sqrt{13})(9\sqrt{13}-9\sqrt{5})(9\sqrt{5}+3\sqrt{13})(9\sqrt{5}-3\sqrt{13})}{16}=108.</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Our answer is <math>\boxed{108}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ~bluesoul | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Note (how to find x and y without the system of equations)==== | ||

| + | To ease computation, we can apply Stewart's Theorem to find <math>x</math>, <math>y</math>, and <math>z</math> directly. Since <math>M(C)=3</math> and <math>M(F)=9</math>, <math>\overline{PC}=15</math> and <math>\overline{PF}=5</math>. We can apply Stewart's Theorem on <math>\triangle CPE</math> to get <math>(2x+x)(2x \cdot x) + 3^2 \cdot 3x = 15^2 \cdot x + 6^2\cdot 2x</math>. Solving, we find that <math>x=3\sqrt{5}</math>. We can do the same on <math>\triangle APB</math> and <math>\triangle BPC</math> to obtain <math>y</math> and <math>z</math>. We proceed with Heron's Formula as the solution states. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ~kn07 | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Solution 6 (easier version of Solution 5)=== | ||

| − | + | In Solution 5, instead of finding all of <math>x, y, z</math>, we only need <math>y, z</math>. This is because after we solve for <math>y, z</math>, we can notice that <math>\triangle BAD</math> is isosceles with <math>AB = BD</math>. Because <math>P</math> is the midpoint of the base, <math>BP</math> is an altitude of <math>\triangle BAD</math>. Therefore, <math>[BAD] = \frac{(AD)(BP)}{2} = \frac{12 \cdot 9}{2} = 54</math>. Using the same altitude property, we can find that <math>[ABC] = 2[BAD] = 2 \cdot 54 = \boxed{108}</math>. | |

| − | + | -NL008 | |

| − | + | === Solution 7 (Mass Points, Stewart's Theorem, Simple Version) === | |

| − | <math> | + | Set <math>AF=x,</math> and use [[mass points]] to find that <math>PF=5</math> and <math>BF=2x.</math> Using [[Stewart's Theorem]] on <math>APB,</math> we find that <math>AB=3\sqrt{13}.</math> Then we notice that <math>APB</math> is right, which means the area of <math>APB</math> is <math>27.</math> Because <math>CF=4\cdot PF,</math> the area of <math>ABC</math> is <math>4</math> times the area of <math>APB,</math> which means the area of <math>ABC=4\cdot 27=\boxed{108}.</math> |

| − | <math> | ||

| − | + | === Solution 8 (Ratios, Auxiliary Lines and 3-4-5 triangle) === | |

| − | + | We try to solve this using only elementary concepts. Let the areas of triangles <math>BCP</math>, <math>ACP</math> and <math>ABP</math> be <math>X</math>, <math>Y</math> and <math>Z</math> respectively. Then <math>\frac{X}{Y+Z}=\frac{6}{6}=1</math> and <math>\frac{Y}{X+Z}=\frac{3}{9}=\frac{1}{3}</math>. Hence <math>\frac{X}{2}=Y=Z</math>. Similarly <math>\frac{FP}{PC}=\frac{Z}{X+Y}=\frac{1}{3}</math> and since <math>CF=20</math> we then have <math>FP=5</math>. Additionally we now see that triangles <math>FPE</math> and <math>CPB</math> are similar, so <math>FE \parallel BC</math> and <math>\frac{FE}{BC} = \frac{1}{3}</math>. Hence <math>\frac{AF}{FB}=\frac{1}{2}</math>. Now construct a point <math>K</math> on segment <math>BP</math> such that <math>BK=6</math> and <math>KP=3</math>, we will have <math>FK \parallel AP</math>, and hence <math>\frac{FK}{AP} = \frac{FK}{6} = \frac{2}{3}</math>, giving <math>FK=4</math>. Triangle <math>FKP</math> is therefore a 3-4-5 triangle! So <math>FK \perp BE</math> and so <math>AP \perp BE</math>. Then it is easy to calculate that <math>Z = \frac{1}{2} \times 6 \times 9 = 27</math> and the area of triangle <math>ABC = X+Y+Z = 4Z = 4 \times 27 = \boxed{108}</math>. | |

| + | ~Leole | ||

| − | |||

| − | === Solution | + | === Solution 9 (Just Trig Bash) === |

| − | + | We start with mass points as in Solution 2, and receive <math>BF:AF = 2</math>, <math>BD:CD = 1</math>, <math>CE:AE = 2</math>. [[Law of Cosines]] on triangles <math>ADB</math> and <math>ADC</math> with <math>\theta = \angle ADB</math> and <math>BD=DC=x</math> gives | |

| − | + | <cmath>36+x^2-12x\cos \theta = 81</cmath> | |

| − | + | <cmath>36+x^2-12x\cos (180-\theta) = 36+x^2+12x\cos \theta = 225</cmath> | |

| − | + | Adding them: <math>72+2x^2=306 \implies x=3\sqrt{13}</math>, so <math>BC = 6\sqrt{13}</math>. Similarly, <math>AB = 3\sqrt{13}</math> and <math>AC = 9\sqrt{5}</math>. Using Heron's, | |

| − | < | + | <cmath>[ \triangle ABC ]= \sqrt{\left(\dfrac{9\sqrt{13}+9\sqrt{5}}{2}\right)\left(\dfrac{9\sqrt{13}09\sqrt{5}}{2}\right)\left(\dfrac{3\sqrt{13}+9\sqrt{5}}{2}\right)\left(\dfrac{-3\sqrt{13}+9\sqrt{5}}{2}\right)} = \boxed{108}.</cmath> |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ~sml1809 | |

| − | |||

| − | ~ | ||

== See also == | == See also == | ||

Latest revision as of 22:46, 30 June 2024

Contents

- 1 Problem

- 2 Solutions

- 2.1 Solution 1 (Ceva's Theorem, Stewart's Theorem)

- 2.2 Solution 2 (Mass Points, Stewart's Theorem, Heron's Formula)

- 2.3 Solution 3 (Ceva's Theorem, Stewart's Theorem)

- 2.4 Solution 4 (Stewart's Theorem)

- 2.5 Solution 5 (Mass of a Point, Stewart's Theorem, Heron's Formula)

- 2.6 Solution 6 (easier version of Solution 5)

- 2.7 Solution 7 (Mass Points, Stewart's Theorem, Simple Version)

- 2.8 Solution 8 (Ratios, Auxiliary Lines and 3-4-5 triangle)

- 2.9 Solution 9 (Just Trig Bash)

- 3 See also

Problem

Point ![]() is inside

is inside ![]() . Line segments

. Line segments ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are drawn with

are drawn with ![]() on

on ![]() ,

, ![]() on

on ![]() , and

, and ![]() on

on ![]() (see the figure below). Given that

(see the figure below). Given that ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , find the area of

, find the area of ![]() .

.

Solutions

Solution 1 (Ceva's Theorem, Stewart's Theorem)

Let ![]() be the area of polygon

be the area of polygon ![]() . We'll make use of the following fact: if

. We'll make use of the following fact: if ![]() is a point in the interior of triangle

is a point in the interior of triangle ![]() , and line

, and line ![]() intersects line

intersects line ![]() at point

at point ![]() , then

, then ![]()

![[asy] size(170); pair X = (1,2), Y = (0,0), Z = (3,0); real x = 0.4, y = 0.2, z = 1-x-y; pair P = x*X + y*Y + z*Z; pair L = y/(y+z)*Y + z/(y+z)*Z; draw(X--Y--Z--cycle); draw(X--P); draw(P--L, dotted); draw(Y--P--Z); label("$X$", X, N); label("$Y$", Y, S); label("$Z$", Z, S); label("$P$", P, NE); label("$L$", L, S);[/asy]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/3/c/9/3c978a1fdb0a6c3a79b9ee477956a440b734f13b.png)

This is true because triangles ![]() and

and ![]() have their areas in ratio

have their areas in ratio ![]() (as they share a common height from

(as they share a common height from ![]() ), and the same is true of triangles

), and the same is true of triangles ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

We'll also use the related fact that ![]() . This is slightly more well known, as it is used in the standard proof of Ceva's theorem.

. This is slightly more well known, as it is used in the standard proof of Ceva's theorem.

Now we'll apply these results to the problem at hand.

![[asy] size(170); pair C = (1, 3), A = (0,0), B = (1.7,0); real a = 0.5, b= 0.25, c = 0.25; pair P = a*A + b*B + c*C; pair D = b/(b+c)*B + c/(b+c)*C; pair EE = c/(c+a)*C + a/(c+a)*A; pair F = a/(a+b)*A + b/(a+b)*B; draw(A--B--C--cycle); draw(A--P); draw(B--P--C); draw(P--D, dotted); draw(EE--P--F, dotted); label("$A$", A, S); label("$B$", B, S); label("$C$", C, N); label("$D$", D, NE); label("$E$", EE, NW); label("$F$", F, S); label("$P$", P, E); [/asy]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/7/c/9/7c9e14d181ecf013675ff1bfbe1aee4cc51d0c7e.png)

Since ![]() , this means that

, this means that ![]() ; thus

; thus ![]() has half the area of

has half the area of ![]() . And since

. And since ![]() , we can conclude that

, we can conclude that ![]() has one third of the combined areas of triangle

has one third of the combined areas of triangle ![]() and

and ![]() , and thus

, and thus ![]() of the area of

of the area of ![]() . This means that

. This means that ![]() is left with

is left with ![]() of the area of triangle

of the area of triangle ![]() :

:

![]() Since

Since ![]() , and since

, and since ![]() , this means that

, this means that ![]() is the midpoint of

is the midpoint of ![]() .

.

Furthermore, we know that ![]() , so

, so ![]() .

.

We now apply Stewart's theorem to segment ![]() in

in ![]() —or rather, the simplified version for a median. This tells us that

—or rather, the simplified version for a median. This tells us that

![]() Plugging in we know, we learn that

Plugging in we know, we learn that

![]() Happily,

Happily, ![]() is also equal to 117. Therefore

is also equal to 117. Therefore ![]() is a right triangle with a right angle at

is a right triangle with a right angle at ![]() ; its area is thus

; its area is thus ![]() . As

. As ![]() is a median of

is a median of ![]() , the area of

, the area of ![]() is twice this, or 54. And we already know that

is twice this, or 54. And we already know that ![]() has half the area of

has half the area of ![]() , which must therefore be

, which must therefore be ![]() .

.

Solution 2 (Mass Points, Stewart's Theorem, Heron's Formula)

Because we're given three concurrent cevians and their lengths, it seems very tempting to apply Mass points. We immediately see that ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . Now, we recall that the masses on the three sides of the triangle must be balanced out, so

. Now, we recall that the masses on the three sides of the triangle must be balanced out, so ![]() and

and ![]() . Thus,

. Thus, ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Recalling that ![]() , we see that

, we see that ![]() and

and ![]() is a median to

is a median to ![]() in

in ![]() . Applying Stewart's Theorem, we have the following:

. Applying Stewart's Theorem, we have the following:

![]() Eliminating

Eliminating ![]() on both sides, we have:

on both sides, we have:

![]() Combining terms and simplifying numbers, we have:

Combining terms and simplifying numbers, we have:

![]() Subtracting 36 to the other side yields:

Subtracting 36 to the other side yields:

![]() Finishing it off from there, we find that

Finishing it off from there, we find that ![]() Now, notice that

Now, notice that ![]() , because both triangles share the same base,

, because both triangles share the same base, ![]() and

and ![]() . Applying Heron's formula on triangle

. Applying Heron's formula on triangle ![]() with sides

with sides ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , we have:

, we have:

![]() Combining terms results in:

Combining terms results in:

![]() Notice that these factors can be grouped into a difference of squares:

Notice that these factors can be grouped into a difference of squares:

![]() Since

Since ![]() , we have:

, we have:

![]() After simplifying this radical, we find that it equals

After simplifying this radical, we find that it equals ![]() Therefore,

Therefore, ![]() , and hence

, and hence ![]() .

.

(The original author made a mistake in their solution. Corrected and further explained by dbnl.)

Solution 3 (Ceva's Theorem, Stewart's Theorem)

Using a different form of Ceva's Theorem, we have ![]()

Solving ![]() and

and ![]() , we obtain

, we obtain ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Let ![]() be the point on

be the point on ![]() such that

such that ![]() .

Since

.

Since ![]() and

and ![]() ,

, ![]() . (Stewart's Theorem)

. (Stewart's Theorem)

Also, since ![]() and

and ![]() , we see that

, we see that ![]() ,

, ![]() , etc. (Stewart's Theorem)

Similarly, we have

, etc. (Stewart's Theorem)

Similarly, we have ![]() (

(![]() ) and thus

) and thus ![]() .

.

![]() is a

is a ![]() right triangle, so

right triangle, so ![]() (

(![]() ) is

) is ![]() .

Therefore, the area of

.

Therefore, the area of ![]() .

Using area ratio,

.

Using area ratio, ![]() .

.

Solution 4 (Stewart's Theorem)

First, let ![]() and

and ![]() Thus, we can easily find that

Thus, we can easily find that ![]() Now,

Now, ![]() In the same manner, we find that

In the same manner, we find that ![]() Now, we can find that

Now, we can find that ![]() We can now use this to find that

We can now use this to find that ![]() Plugging this value in, we find that

Plugging this value in, we find that ![]() Now, since

Now, since ![]() we can find that

we can find that ![]() Setting

Setting ![]() we can apply Stewart's Theorem on triangle

we can apply Stewart's Theorem on triangle ![]() to find that

to find that ![]() Solving, we find that

Solving, we find that ![]() But,

But, ![]() meaning that

meaning that ![]() Since

Since ![]() we conclude that the answer is

we conclude that the answer is ![]() .

.

Solution 5 (Mass of a Point, Stewart's Theorem, Heron's Formula)

Firstly, since they all meet at one single point, denoting the mass of them separately. Assuming ![]() ; we can get that

; we can get that ![]() ; which leads to the ratio between segments,

; which leads to the ratio between segments,

![]() Denoting that

Denoting that ![]()

Now we know three cevians' length, Applying Stewart theorem to them, getting three different equations:

After solving the system of equation, we get that

After solving the system of equation, we get that ![]() ;

;

pulling ![]() back to get the length of

back to get the length of ![]() ; now we can apply Heron's formula here, which is

; now we can apply Heron's formula here, which is ![\[\sqrt\frac{(9\sqrt{5}+9\sqrt{13})(9\sqrt{13}-9\sqrt{5})(9\sqrt{5}+3\sqrt{13})(9\sqrt{5}-3\sqrt{13})}{16}=108.\]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/a/f/e/afe1b2a9adbe5bff16bc84ceb033d8a5f08d4dab.png)

Our answer is ![]() .

.

~bluesoul

Note (how to find x and y without the system of equations)

To ease computation, we can apply Stewart's Theorem to find ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() directly. Since

directly. Since ![]() and

and ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() . We can apply Stewart's Theorem on

. We can apply Stewart's Theorem on ![]() to get

to get ![]() . Solving, we find that

. Solving, we find that ![]() . We can do the same on

. We can do the same on ![]() and

and ![]() to obtain

to obtain ![]() and

and ![]() . We proceed with Heron's Formula as the solution states.

. We proceed with Heron's Formula as the solution states.

~kn07

Solution 6 (easier version of Solution 5)

In Solution 5, instead of finding all of ![]() , we only need

, we only need ![]() . This is because after we solve for

. This is because after we solve for ![]() , we can notice that

, we can notice that ![]() is isosceles with

is isosceles with ![]() . Because

. Because ![]() is the midpoint of the base,

is the midpoint of the base, ![]() is an altitude of

is an altitude of ![]() . Therefore,

. Therefore, ![]() . Using the same altitude property, we can find that

. Using the same altitude property, we can find that ![]() .

.

-NL008

Solution 7 (Mass Points, Stewart's Theorem, Simple Version)

Set ![]() and use mass points to find that

and use mass points to find that ![]() and

and ![]() Using Stewart's Theorem on

Using Stewart's Theorem on ![]() we find that

we find that ![]() Then we notice that

Then we notice that ![]() is right, which means the area of

is right, which means the area of ![]() is

is ![]() Because

Because ![]() the area of

the area of ![]() is

is ![]() times the area of

times the area of ![]() which means the area of

which means the area of ![]()

Solution 8 (Ratios, Auxiliary Lines and 3-4-5 triangle)

We try to solve this using only elementary concepts. Let the areas of triangles ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() be

be ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() respectively. Then

respectively. Then ![]() and

and ![]() . Hence

. Hence ![]() . Similarly

. Similarly ![]() and since

and since ![]() we then have

we then have ![]() . Additionally we now see that triangles

. Additionally we now see that triangles ![]() and

and ![]() are similar, so

are similar, so ![]() and

and ![]() . Hence

. Hence ![]() . Now construct a point

. Now construct a point ![]() on segment

on segment ![]() such that

such that ![]() and

and ![]() , we will have

, we will have ![]() , and hence

, and hence ![]() , giving

, giving ![]() . Triangle

. Triangle ![]() is therefore a 3-4-5 triangle! So

is therefore a 3-4-5 triangle! So ![]() and so

and so ![]() . Then it is easy to calculate that

. Then it is easy to calculate that ![]() and the area of triangle

and the area of triangle ![]() .

~Leole

.

~Leole

Solution 9 (Just Trig Bash)

We start with mass points as in Solution 2, and receive ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() . Law of Cosines on triangles

. Law of Cosines on triangles ![]() and

and ![]() with

with ![]() and

and ![]() gives

gives

![]()

![]() Adding them:

Adding them: ![]() , so

, so ![]() . Similarly,

. Similarly, ![]() and

and ![]() . Using Heron's,

. Using Heron's,

![\[[ \triangle ABC ]= \sqrt{\left(\dfrac{9\sqrt{13}+9\sqrt{5}}{2}\right)\left(\dfrac{9\sqrt{13}09\sqrt{5}}{2}\right)\left(\dfrac{3\sqrt{13}+9\sqrt{5}}{2}\right)\left(\dfrac{-3\sqrt{13}+9\sqrt{5}}{2}\right)} = \boxed{108}.\]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/d/b/4/db428f58c040f161bdb0ba1b4cd039d208c6994d.png)

~sml1809

See also

| 1989 AIME (Problems • Answer Key • Resources) | ||

| Preceded by Problem 14 |

Followed by Final Question | |

| 1 • 2 • 3 • 4 • 5 • 6 • 7 • 8 • 9 • 10 • 11 • 12 • 13 • 14 • 15 | ||

| All AIME Problems and Solutions | ||

The problems on this page are copyrighted by the Mathematical Association of America's American Mathematics Competitions.