Difference between revisions of "1996 AHSME Problems/Problem 27"

(→Solution 2) |

Isabelchen (talk | contribs) m (→Solution 3) |

||

| (35 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

Thus, there are <math>\boxed{13}</math> possible points, giving answer <math>\boxed{D}</math>. | Thus, there are <math>\boxed{13}</math> possible points, giving answer <math>\boxed{D}</math>. | ||

| − | ==Solution 2== | + | ==Solution 2 (minimal 3D geometry)== |

| − | Because both spheres have their centers on the x-axis, we can simplify the graph a bit by looking at a | + | Because both spheres have their centers on the x-axis, we can simplify the graph a bit by looking at a 2-dimensional plane (the previous z-axis is the new x-axis while the y-axis remains the same). |

| − | The spheres now become circles with centers at <math>(1,0)</math> and (21 | + | The spheres now become circles with centers at <math>(1,0)</math> and <math>(\frac{21}{2},0)</math>. They have radii <math>\frac{9}{2}</math> and <math>6</math>, respectively. |

| − | Let circle < | + | Let circle <math>A</math> be the circle centered on <math>(1,0)</math> and circle <math>B</math> be the one centered on <math>(\frac{21}{2},0)</math>. |

| − | The point on circle < | + | The point on circle <math>A</math> closest to the center of circle <math>B</math> is <math>(\frac{11}{2},0)</math>. The point on circle B closest to the center of circle <math>A</math> is <math>(\frac{11}{2},0)</math>. |

| + | |||

| + | Taking a look back at the 3-dimensional coordinate grid with the spheres, we can see that their intersection appears to be a circle with congruent "dome" shapes on either end. Because the tops of the "domes" are at <math>(0,0,\frac{9}{2})</math> and <math>(0,0,\frac{11}{2})</math>, respectively, the lattice points inside the area of intersection must have z-value <math>5</math> (because <math>5</math> is the only integer between <math>\frac{9}{2}</math> and <math>\frac{11}{2}</math>). Thus, the lattice points in the area of intersection must all be on the 2-dimensional circle. The radius of the circle will be the distance from the z-axis. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Now, looking at the 2-dimensional coordinate plane, we see that the radius of the circle (now the distance from the x-axis, because there is no more z-axis) is the altitude of a triangle with two points on centers of circles <math>A</math> and <math>B</math> and third point at the first quadrant intersection of the circles. Let's call that altitude <math>h</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | We know all three side lengths of this triangle: <math>\frac{9}{2}</math> (the radius of circle <math>A</math>), <math>6</math> (the radius of circle <math>B</math>), and <math>\frac{19}{2}</math> (the distance between the centers of circles <math>A</math> and <math>B</math>). We can now find the area of the triangle using Heron's formula: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <cmath>s=\frac{\frac{9}{2}+6+\frac{19}{2}}{2}=20</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <cmath>A=\sqrt{(20)(20-\frac{9}{2})(20-6)(20-\frac{19}{2})}=\sqrt{110}</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Using the area of the triangle, we can find that altitude <math>h</math> from the x-axis: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <cmath>\sqrt{110}=\frac{h*\frac{19}{2}}{2}</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <cmath>h=\frac{4*\sqrt{110}}{19}</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Remember, the altitude <math>h</math> is also the radius of the circle containing all the solutions to the problem. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Going back to the 3-dimensional grid and looking at the circle, we can again make the figure 2-dimensional. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The radius <math>h</math> of the circle in a 2-dimensional plane is <math>\frac{4\sqrt{110}}{19}</math>, a little greater than <math>2</math>. We know that <math>h>2</math> because <math>4\sqrt{110}>4*10</math>, and <math>\frac{40}{19}>2</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Finally, looking at a circle with radius slightly larger than <math>2</math>, we see that there are <math>\boxed{13}</math> lattice points within it <math>\boxed{D}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 3== | ||

| + | |||

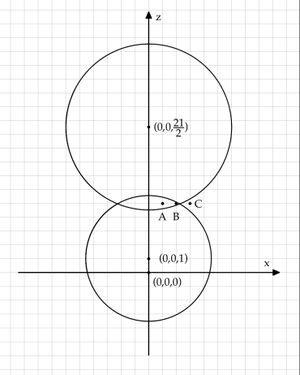

| + | Note that the spheres are on the same <math>x</math> and <math>y</math> axis. Therefore, we can draw the spheres so that only the <math>x</math> and <math>z</math> axis are featured. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:1996AHSMEP271.jpg|300px|center]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>A = (1, 0, 5)</math>. <math>\sqrt{1^2+4^2} = \sqrt{17}<\frac92</math>, <math>A</math> is inside the smaller sphere. <math>\sqrt{1^2+(\frac{11}{2})^2} = \frac{\sqrt{126}}{2}<6</math>, <math>A</math> is inside the larger sphere. Point <math>A</math> is inside the intersection. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>B = (2, 0, 5)</math>, <math>\sqrt{2^2+4^2} = \sqrt{20}<\frac92</math>, <math>B</math> is inside the smaller sphere. <math>\sqrt{2^2+(\frac{11}{2})^2} = \frac{\sqrt{137}}{2}<6</math>, <math>B</math> is inside the larger sphere. Point <math>B</math> is inside the intersection. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>C = (3, 0, 5)</math>, <math>\sqrt{3^2+4^2} = \sqrt{25}>\frac92</math>, <math>C</math> is outside the smaller sphere. <math>\sqrt{3^2+(\frac{11}{2})^2} = \frac{\sqrt{157}}{2}>6</math>, <math>C</math> is outside the larger sphere. Point <math>C</math> is outside the intersection. | ||

| + | |||

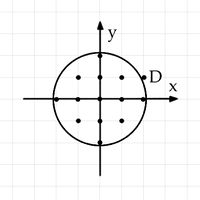

| + | The intersection of <math>2</math> spheres is a circle, by drawing the circle flat we can see that there are <math>4</math> more points within the intersection. | ||

| + | |||

| + | We can see that points with the same <math>x</math>-coordinates with <math>A</math> are still inside the circle. <math>B</math> is very close to the circle, the points with the same <math>x</math>-coordinates with <math>B</math> are not necessarily inside the circle. | ||

| + | |||

| + | For example, <math>D = (2,1,5)</math>, <math>\sqrt{2^2+1^2+4^2}=\sqrt{21}>\frac92</math>, <math>D</math> is outside the smaller sphere. <math>\sqrt{2^2 + 1^2 + (\frac{11}{2})^2} = \frac{\sqrt{141}}{2}<6</math>, <math>D</math> is inside the larger sphere. Point <math>D</math> is outside the intersection. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:1996AHSMEP272.jpg|200px|center]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Therefore, the answer is <math>9+4 = \boxed{\textbf{(D) } 13}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ~[https://artofproblemsolving.com/wiki/index.php/User:Isabelchen isabelchen] | ||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

{{AHSME box|year=1996|num-b=26|num-a=28}} | {{AHSME box|year=1996|num-b=26|num-a=28}} | ||

{{MAA Notice}} | {{MAA Notice}} | ||

Latest revision as of 10:42, 30 September 2023

Problem

Consider two solid spherical balls, one centered at ![]() with radius

with radius ![]() , and the other centered at

, and the other centered at ![]() with radius

with radius ![]() . How many points with only integer coordinates (lattice points) are there in the intersection of the balls?

. How many points with only integer coordinates (lattice points) are there in the intersection of the balls?

![]()

Solution 1

The two equations of the balls are

![]()

![]()

Note that along the ![]() axis, the first ball goes from

axis, the first ball goes from ![]() , and the second ball goes from

, and the second ball goes from ![]() . The only integer value that

. The only integer value that ![]() can be is

can be is ![]() .

.

Plugging that in to both equations, we get:

![]()

![]()

The second inequality implies the first inequality, so the only condition that matters is the second inequality.

From here, we do casework, noting that ![]() :

:

For ![]() , we must have

, we must have ![]() . This gives

. This gives ![]() points.

points.

For ![]() , we can have

, we can have ![]() . This gives

. This gives ![]() points.

points.

For ![]() , we can have

, we can have ![]() . This gives

. This gives ![]() points.

points.

Thus, there are ![]() possible points, giving answer

possible points, giving answer ![]() .

.

Solution 2 (minimal 3D geometry)

Because both spheres have their centers on the x-axis, we can simplify the graph a bit by looking at a 2-dimensional plane (the previous z-axis is the new x-axis while the y-axis remains the same).

The spheres now become circles with centers at ![]() and

and ![]() . They have radii

. They have radii ![]() and

and ![]() , respectively.

Let circle

, respectively.

Let circle ![]() be the circle centered on

be the circle centered on ![]() and circle

and circle ![]() be the one centered on

be the one centered on ![]() .

.

The point on circle ![]() closest to the center of circle

closest to the center of circle ![]() is

is ![]() . The point on circle B closest to the center of circle

. The point on circle B closest to the center of circle ![]() is

is ![]() .

.

Taking a look back at the 3-dimensional coordinate grid with the spheres, we can see that their intersection appears to be a circle with congruent "dome" shapes on either end. Because the tops of the "domes" are at ![]() and

and ![]() , respectively, the lattice points inside the area of intersection must have z-value

, respectively, the lattice points inside the area of intersection must have z-value ![]() (because

(because ![]() is the only integer between

is the only integer between ![]() and

and ![]() ). Thus, the lattice points in the area of intersection must all be on the 2-dimensional circle. The radius of the circle will be the distance from the z-axis.

). Thus, the lattice points in the area of intersection must all be on the 2-dimensional circle. The radius of the circle will be the distance from the z-axis.

Now, looking at the 2-dimensional coordinate plane, we see that the radius of the circle (now the distance from the x-axis, because there is no more z-axis) is the altitude of a triangle with two points on centers of circles ![]() and

and ![]() and third point at the first quadrant intersection of the circles. Let's call that altitude

and third point at the first quadrant intersection of the circles. Let's call that altitude ![]() .

.

We know all three side lengths of this triangle: ![]() (the radius of circle

(the radius of circle ![]() ),

), ![]() (the radius of circle

(the radius of circle ![]() ), and

), and ![]() (the distance between the centers of circles

(the distance between the centers of circles ![]() and

and ![]() ). We can now find the area of the triangle using Heron's formula:

). We can now find the area of the triangle using Heron's formula:

![]()

![]()

Using the area of the triangle, we can find that altitude ![]() from the x-axis:

from the x-axis:

![]()

![]()

Remember, the altitude ![]() is also the radius of the circle containing all the solutions to the problem.

is also the radius of the circle containing all the solutions to the problem.

Going back to the 3-dimensional grid and looking at the circle, we can again make the figure 2-dimensional.

The radius ![]() of the circle in a 2-dimensional plane is

of the circle in a 2-dimensional plane is ![]() , a little greater than

, a little greater than ![]() . We know that

. We know that ![]() because

because ![]() , and

, and ![]() .

.

Finally, looking at a circle with radius slightly larger than ![]() , we see that there are

, we see that there are ![]() lattice points within it

lattice points within it ![]() .

.

Solution 3

Note that the spheres are on the same ![]() and

and ![]() axis. Therefore, we can draw the spheres so that only the

axis. Therefore, we can draw the spheres so that only the ![]() and

and ![]() axis are featured.

axis are featured.

![]() .

. ![]() ,

, ![]() is inside the smaller sphere.

is inside the smaller sphere. ![]() ,

, ![]() is inside the larger sphere. Point

is inside the larger sphere. Point ![]() is inside the intersection.

is inside the intersection.

![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() is inside the smaller sphere.

is inside the smaller sphere. ![]() ,

, ![]() is inside the larger sphere. Point

is inside the larger sphere. Point ![]() is inside the intersection.

is inside the intersection.

![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() is outside the smaller sphere.

is outside the smaller sphere. ![]() ,

, ![]() is outside the larger sphere. Point

is outside the larger sphere. Point ![]() is outside the intersection.

is outside the intersection.

The intersection of ![]() spheres is a circle, by drawing the circle flat we can see that there are

spheres is a circle, by drawing the circle flat we can see that there are ![]() more points within the intersection.

more points within the intersection.

We can see that points with the same ![]() -coordinates with

-coordinates with ![]() are still inside the circle.

are still inside the circle. ![]() is very close to the circle, the points with the same

is very close to the circle, the points with the same ![]() -coordinates with

-coordinates with ![]() are not necessarily inside the circle.

are not necessarily inside the circle.

For example, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() is outside the smaller sphere.

is outside the smaller sphere. ![]() ,

, ![]() is inside the larger sphere. Point

is inside the larger sphere. Point ![]() is outside the intersection.

is outside the intersection.

Therefore, the answer is ![]() .

.

See also

| 1996 AHSME (Problems • Answer Key • Resources) | ||

| Preceded by Problem 26 |

Followed by Problem 28 | |

| 1 • 2 • 3 • 4 • 5 • 6 • 7 • 8 • 9 • 10 • 11 • 12 • 13 • 14 • 15 • 16 • 17 • 18 • 19 • 20 • 21 • 22 • 23 • 24 • 25 • 26 • 27 • 28 • 29 • 30 | ||

| All AHSME Problems and Solutions | ||

The problems on this page are copyrighted by the Mathematical Association of America's American Mathematics Competitions. ![]()