Difference between revisions of "Orthic triangle"

Etmetalakret (talk | contribs) |

m (→Incenter of the orthic triangle) |

||

| (22 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

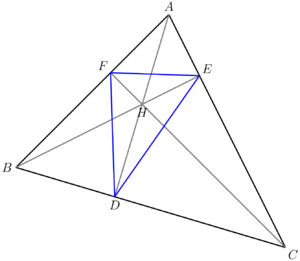

| − | + | [[Image:Acute_orthic_triangle.png|thumb|right|300px|Case 1: <math>\triangle ABC</math> is acute.]] | |

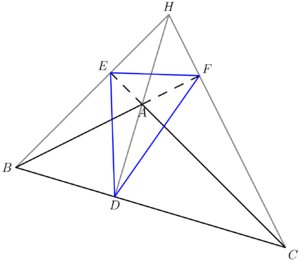

| − | + | [[Image:Obtuse_orthic_triangle.png|thumb|right|300px|Case 2: <math>\triangle ABC</math> is obtuse.]] | |

In [[geometry]], given any <math>\triangle ABC</math>, let <math>D</math>, <math>E</math>, and <math>F</math> denote the feet of the altitudes from <math>A</math>, <math>B</math>, and <math>C</math>, respectively. Then, <math>\triangle DEF</math> is called the '''orthic triangle''' of <math>\triangle ABC</math>. | In [[geometry]], given any <math>\triangle ABC</math>, let <math>D</math>, <math>E</math>, and <math>F</math> denote the feet of the altitudes from <math>A</math>, <math>B</math>, and <math>C</math>, respectively. Then, <math>\triangle DEF</math> is called the '''orthic triangle''' of <math>\triangle ABC</math>. | ||

| − | + | The orthic triangle does not exist if <math>\triangle ABC</math> is right. The two cases of when <math>\triangle ABC</math> is either acute or obtuse each carry different characteristics and must be handled separately. | |

| − | Orthic triangles are not unique to their mother | + | Orthic triangles are not unique to their mother triangle; one acute and one to three obtuse triangles are guaranteed to have the same orthic triangle. To see this, take an acute triangle and swap its orthocenter and any vertex to get an obtuse triangle. It is easy to verify that this placement of the orthocenter is correct and that the orthic triangle will remain the same as before the swapping, as seen in the diagrams to the right. |

== Cyclic quadrilaterals == | == Cyclic quadrilaterals == | ||

| − | In both the acute and obtuse case, quadrilaterals <math>ADEB</math>, <math>BEFC</math>, <math> | + | In both the acute and obtuse case, quadrilaterals <math>ADEB</math>, <math>BEFC</math>, <math>CFAD</math>, <math>AEHF</math>, <math>BFHD</math>, and <math>CDHE</math> are [[Cyclic quadrilateral | cyclic]]. These cyclic quadrilaterals make frequent appearances in olympiad geometry and are the most crucial section of this article. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ''Proof'': we will be using [[directed angles]], denoted by <math>\measuredangle</math> instead of the conventional <math>\angle</math>. We know that <cmath>\measuredangle ADB = 90^{\circ} = \measuredangle AEB,</cmath> and thus <math>AEDB</math> is cyclic. In addition, <cmath>\measuredangle AEH = 90^{\circ} = \measuredangle AFH,</cmath> so <math>AEHF</math> is also cyclic. It follows that the other cyclic quadrilaterals are also cyclic. | |

| + | <math>\square</math> | ||

== Connection with incenters and excenters == | == Connection with incenters and excenters == | ||

=== Incenter of the orthic triangle === | === Incenter of the orthic triangle === | ||

| − | If <math>\triangle ABC</math> is acute, then the incenter of the orthic triangle is the orthocenter <math>H</math>. | + | If <math>\triangle ABC</math> is acute, then the incenter of the orthic triangle of <math>\triangle ABC</math> is the orthocenter <math>H</math>. |

| + | |||

| + | ''Proof'': Let <math>\theta = \angle EAH</math>. Since <math>\angle ADC = 90^\circ</math>, we have that <math>\theta = 90^\circ - \angle C</math>. The quadrilateral <math>EAFH</math> is cyclic and, in fact <math>E</math> and <math>F</math> lie on the circle with diameter <math>AH</math>. Since <math>EH</math> subtends <math>\theta</math> as well as <math>\angle EFH</math> on this circle, so <math>\angle EFH = \theta = 90^\circ - \angle C</math>. The same argument (with <math>FBDH</math> instead of <math>EAFH</math>) shows that <math>\angle DFH = 90^\circ - \angle C</math>. Hence <math>\angle EFH = \angle DFH</math>, i.e. the line <math>HF</math> bisects <math>\angle EFD</math>. By the same reasoning <math>HD</math> bisects <math>\angle EDF</math> and <math>HE</math> bisects <math>\angle FED</math>. | ||

| + | <math>\square</math> | ||

| − | If <math>\triangle ABC</math> is obtuse, then the incenter of the orthic triangle is the obtuse vertex. | + | If <math>\triangle ABC</math> is obtuse, then the incenter of the orthic triangle of <math>\triangle ABC</math> is the obtuse vertex. |

=== Excenters of the orthic triangle === | === Excenters of the orthic triangle === | ||

| − | For any <math>\triangle ABC</math> and <math>\triangle DEF</math>, <math>\triangle DEF</math> is the orthic triangle of <math>\triangle ABC</math> if and only if <math>A</math>, <math>B</math>, and <math>C</math> are the excenters of <math>\triangle DEF</math>. | + | For any acute <math>\triangle ABC</math> and any <math>\triangle DEF</math>, <math>\triangle DEF</math> is the orthic triangle of <math>\triangle ABC</math> if and only if <math>A</math>, <math>B</math>, and <math>C</math> are the excenters of <math>\triangle DEF</math>. |

| − | |||

| − | + | ''Proof'': First, we show that the orthic triangle leads to the excenters. Let <math>D</math>, <math>E</math>, and <math>F</math> be on <math>\overline{AB}</math>, <math>\overline{BC}</math>, and <math>\overline{CA}</math>, respectively. Because <math>ADEB</math> is cyclic, <math>\angle EDC = \angle A</math>. Likewise, <math>\angle BDF = \angle A</math> as well. Then because <math>\angle BDF + \angle D + \angle EDC = 180^{\circ}</math>, <math>\angle A + \angle D + \angle A = 180^{\circ}</math> and so <math>\angle D = 180^{\circ} - 2\angle A</math>. | |

| + | |||

| + | Thus, the exterior angle of <math>\angle D</math> is <math>2\angle A</math>. But <math>\angle BDF = \angle EDC = \angle A</math>, so <math>\overline{BC}</math> bisects the exterior angle of <math>\angle D</math>. Similarly, <math>\overline{CA}</math> and <math>\overline{AB}</math> bisect the exterior angles of <math>\angle E</math> and <math>\angle F</math> respectively. Thus, the intersections of <math>\overline{AB}</math>, <math>\overline{BC}</math>, and <math>\overline{CA}</math> (namely <math>A</math>, <math>B</math>, and <math>C</math>) are the excenters of <math>\triangle DEF</math>, and we are halfway finished. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Next, we show that the excenters lead to the orthic triangle. Let <math>A</math>, <math>B</math>, and <math>C</math> be the <math>D</math>-excenter, <math>E</math>-excenter, and <math>F</math>-excenter of <math>\triangle DEF</math>, and let <math>H</math> be the incenter of <math>\triangle DEF</math>. <math>A</math> is equidistant from <math>\overline{DE}</math> and <math>\overline{FE}</math>, so <math>A</math> is on <math>\overline{DH}</math>; as a result, <math>\overline{AH}</math> is an internal angle bisector of <math>\angle D</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | We know that <math>\angle ADE = \frac{1}{2} \angle D</math> and because <math>C</math> is an <math>F</math>-excenter of <math>\triangle DEF</math>, <math>\angle EDC = 90^{\circ} - \frac{1}{2} \angle D</math>. Thus, <math>\angle ADC = 90^{\circ}</math>, and because <math>D</math> is on <math>\overline{BC}</math>, <math>D</math> is the foot of the altitude from <math>A</math> of <math>\triangle ABC</math>. Similarly, <math>E</math> and <math>F</math> are feet of the altitudes from <math>B</math> and <math>C</math>, respectively. Then <math>\triangle DEF</math> is the orthic triangle of <math>\triangle ABC</math>, and we are done. | ||

| + | <math>\square</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | This lemma makes frequent appearances in olympiad geometry. Problems written in either excenters or the orthic triangle can often be solved by shifting perspective to the other, via the medium of this lemma. Also, note the converse works as well. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the obtuse case, the two vertices with acute angles and the [[orthocenter]] of <math>\triangle ABC</math> are the excenters. | ||

=== Relationship with the incenter/excenter lemma === | === Relationship with the incenter/excenter lemma === | ||

| − | With this knowledge in mind, we can transfer results about the incenter and excenters to the orthic triangle. In particular, the [[incenter/excenter lemma]] can be translated into the language of the orthic triangle. It tells that all six cyclic quadrilaterals of the orthic triangle have a circumcenter on the nine-point circle of <math>\triangle ABC</math>. | + | With this knowledge in mind, we can transfer results about the incenter and excenters to the orthic triangle. In particular, the [[incenter/excenter lemma]] can be translated into the language of the orthic triangle. It tells that all six cyclic quadrilaterals of the orthic triangle have a circumcenter on the [[nine-point circle]] of <math>\triangle ABC</math>. |

| + | |||

| + | In the case where <math>\triangle ABC</math> is acute, quadrilaterals <math>AEHF</math>, <math>BFHD</math>, and <math>CDHE</math> follow immediately from the lemma. Actually, because <math>\angle AEH = 90^{\circ}</math>, the circumcenter of <math>AEHF</math> is the midpoint of <math>A</math> and <math>H</math>, called an Euler point. It follows that the circumcenters of <math>BFHD</math> and <math>CDHE</math> are the other two Euler points. | ||

| + | |||

| + | As for <math>ADEB</math>, <math>BEFC</math>, and <math>CFDA</math>, via the [[inscribed angle theorem]], their circumcenters are the midpoints of the side lengths of <math>\triangle ABC</math>, which we know to be on the nine-point circle. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Identical reasoning follows that in the obtuse case, the six cyclic quadrilaterals still have circumcenters on the nine-point circle. | ||

| − | In the | + | == Problems == |

| + | * In acute triangle <math>ABC</math> points <math>P</math> and <math>Q</math> are the feet of the perpendiculars from <math>C</math> to <math>\overline{AB}</math> and from <math>B</math> to <math>\overline{AC}</math>, respectively. Line <math>PQ</math> intersects the circumcircle of <math>\triangle ABC</math> in two distinct points, <math>X</math> and <math>Y</math>. Suppose <math>XP=10</math>, <math>PQ=25</math>, and <math>QY=15</math>. Compute the product <math>AB\cdot AC</math>. (AIME II, 2019, 15) | ||

| + | ===Olympiad=== | ||

| + | * Let <math>\triangle ABC</math> be an acute triangle with <math>D</math>, <math>E</math>, <math>F</math> the feet of the altitudes lying on <math>\overline{BC}</math>, <math>\overline{CA}</math>, and <math>\overline{AB}</math> respectively. One of the intersection points of the line <math>\overline{EF}</math> and the circumcircle is <math>P</math>. The lines <math>\overline{BP}</math> and <math>\overline{DF}</math> meet at point <math>Q</math>. Prove that <math>|AP| = |AQ|</math>. (IMO Shortlist 2010 G1) | ||

== See also == | == See also == | ||

| − | * | + | * [[Incenter/excenter lemma]] |

| + | * [[Geometry/Olympiad | Olympiad geometry]] | ||

[[Category:Geometry]] | [[Category:Geometry]] | ||

| − | + | [[Category:Definition]] | |

| − | [[Category: | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Latest revision as of 08:39, 10 July 2024

In geometry, given any ![]() , let

, let ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() denote the feet of the altitudes from

denote the feet of the altitudes from ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , respectively. Then,

, respectively. Then, ![]() is called the orthic triangle of

is called the orthic triangle of ![]() .

.

The orthic triangle does not exist if ![]() is right. The two cases of when

is right. The two cases of when ![]() is either acute or obtuse each carry different characteristics and must be handled separately.

is either acute or obtuse each carry different characteristics and must be handled separately.

Orthic triangles are not unique to their mother triangle; one acute and one to three obtuse triangles are guaranteed to have the same orthic triangle. To see this, take an acute triangle and swap its orthocenter and any vertex to get an obtuse triangle. It is easy to verify that this placement of the orthocenter is correct and that the orthic triangle will remain the same as before the swapping, as seen in the diagrams to the right.

Contents

[hide]Cyclic quadrilaterals

In both the acute and obtuse case, quadrilaterals ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are cyclic. These cyclic quadrilaterals make frequent appearances in olympiad geometry and are the most crucial section of this article.

are cyclic. These cyclic quadrilaterals make frequent appearances in olympiad geometry and are the most crucial section of this article.

Proof: we will be using directed angles, denoted by ![]() instead of the conventional

instead of the conventional ![]() . We know that

. We know that ![]() and thus

and thus ![]() is cyclic. In addition,

is cyclic. In addition, ![]() so

so ![]() is also cyclic. It follows that the other cyclic quadrilaterals are also cyclic.

is also cyclic. It follows that the other cyclic quadrilaterals are also cyclic.

![]()

Connection with incenters and excenters

Incenter of the orthic triangle

If ![]() is acute, then the incenter of the orthic triangle of

is acute, then the incenter of the orthic triangle of ![]() is the orthocenter

is the orthocenter ![]() .

.

Proof: Let ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() , we have that

, we have that ![]() . The quadrilateral

. The quadrilateral ![]() is cyclic and, in fact

is cyclic and, in fact ![]() and

and ![]() lie on the circle with diameter

lie on the circle with diameter ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() subtends

subtends ![]() as well as

as well as ![]() on this circle, so

on this circle, so ![]() . The same argument (with

. The same argument (with ![]() instead of

instead of ![]() ) shows that

) shows that ![]() . Hence

. Hence ![]() , i.e. the line

, i.e. the line ![]() bisects

bisects ![]() . By the same reasoning

. By the same reasoning ![]() bisects

bisects ![]() and

and ![]() bisects

bisects ![]() .

.

![]()

If ![]() is obtuse, then the incenter of the orthic triangle of

is obtuse, then the incenter of the orthic triangle of ![]() is the obtuse vertex.

is the obtuse vertex.

Excenters of the orthic triangle

For any acute ![]() and any

and any ![]() ,

, ![]() is the orthic triangle of

is the orthic triangle of ![]() if and only if

if and only if ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are the excenters of

are the excenters of ![]() .

.

Proof: First, we show that the orthic triangle leads to the excenters. Let ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() be on

be on ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , respectively. Because

, respectively. Because ![]() is cyclic,

is cyclic, ![]() . Likewise,

. Likewise, ![]() as well. Then because

as well. Then because ![]() ,

, ![]() and so

and so ![]() .

.

Thus, the exterior angle of ![]() is

is ![]() . But

. But ![]() , so

, so ![]() bisects the exterior angle of

bisects the exterior angle of ![]() . Similarly,

. Similarly, ![]() and

and ![]() bisect the exterior angles of

bisect the exterior angles of ![]() and

and ![]() respectively. Thus, the intersections of

respectively. Thus, the intersections of ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() (namely

(namely ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() ) are the excenters of

) are the excenters of ![]() , and we are halfway finished.

, and we are halfway finished.

Next, we show that the excenters lead to the orthic triangle. Let ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() be the

be the ![]() -excenter,

-excenter, ![]() -excenter, and

-excenter, and ![]() -excenter of

-excenter of ![]() , and let

, and let ![]() be the incenter of

be the incenter of ![]() .

. ![]() is equidistant from

is equidistant from ![]() and

and ![]() , so

, so ![]() is on

is on ![]() ; as a result,

; as a result, ![]() is an internal angle bisector of

is an internal angle bisector of ![]() .

.

We know that ![]() and because

and because ![]() is an

is an ![]() -excenter of

-excenter of ![]() ,

, ![]() . Thus,

. Thus, ![]() , and because

, and because ![]() is on

is on ![]() ,

, ![]() is the foot of the altitude from

is the foot of the altitude from ![]() of

of ![]() . Similarly,

. Similarly, ![]() and

and ![]() are feet of the altitudes from

are feet of the altitudes from ![]() and

and ![]() , respectively. Then

, respectively. Then ![]() is the orthic triangle of

is the orthic triangle of ![]() , and we are done.

, and we are done.

![]()

This lemma makes frequent appearances in olympiad geometry. Problems written in either excenters or the orthic triangle can often be solved by shifting perspective to the other, via the medium of this lemma. Also, note the converse works as well.

In the obtuse case, the two vertices with acute angles and the orthocenter of ![]() are the excenters.

are the excenters.

Relationship with the incenter/excenter lemma

With this knowledge in mind, we can transfer results about the incenter and excenters to the orthic triangle. In particular, the incenter/excenter lemma can be translated into the language of the orthic triangle. It tells that all six cyclic quadrilaterals of the orthic triangle have a circumcenter on the nine-point circle of ![]() .

.

In the case where ![]() is acute, quadrilaterals

is acute, quadrilaterals ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() follow immediately from the lemma. Actually, because

follow immediately from the lemma. Actually, because ![]() , the circumcenter of

, the circumcenter of ![]() is the midpoint of

is the midpoint of ![]() and

and ![]() , called an Euler point. It follows that the circumcenters of

, called an Euler point. It follows that the circumcenters of ![]() and

and ![]() are the other two Euler points.

are the other two Euler points.

As for ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , via the inscribed angle theorem, their circumcenters are the midpoints of the side lengths of

, via the inscribed angle theorem, their circumcenters are the midpoints of the side lengths of ![]() , which we know to be on the nine-point circle.

, which we know to be on the nine-point circle.

Identical reasoning follows that in the obtuse case, the six cyclic quadrilaterals still have circumcenters on the nine-point circle.

Problems

- In acute triangle

points

points  and

and  are the feet of the perpendiculars from

are the feet of the perpendiculars from  to

to  and from

and from  to

to  , respectively. Line

, respectively. Line  intersects the circumcircle of

intersects the circumcircle of  in two distinct points,

in two distinct points,  and

and  . Suppose

. Suppose  ,

,  , and

, and  . Compute the product

. Compute the product  . (AIME II, 2019, 15)

. (AIME II, 2019, 15)

Olympiad

- Let

be an acute triangle with

be an acute triangle with  ,

,  ,

,  the feet of the altitudes lying on

the feet of the altitudes lying on  ,

,  , and

, and  respectively. One of the intersection points of the line

respectively. One of the intersection points of the line  and the circumcircle is

and the circumcircle is  . The lines

. The lines  and

and  meet at point

meet at point  . Prove that

. Prove that  . (IMO Shortlist 2010 G1)

. (IMO Shortlist 2010 G1)