Difference between revisions of "2015 AIME II Problems/Problem 15"

m (→Solution) |

m (→Solution 11 (Trig)) |

||

| (62 intermediate revisions by 21 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

Circles <math>\mathcal{P}</math> and <math>\mathcal{Q}</math> have radii <math>1</math> and <math>4</math>, respectively, and are externally tangent at point <math>A</math>. Point <math>B</math> is on <math>\mathcal{P}</math> and point <math>C</math> is on <math>\mathcal{Q}</math> so that line <math>BC</math> is a common external tangent of the two circles. A line <math>\ell</math> through <math>A</math> intersects <math>\mathcal{P}</math> again at <math>D</math> and intersects <math>\mathcal{Q}</math> again at <math>E</math>. Points <math>B</math> and <math>C</math> lie on the same side of <math>\ell</math>, and the areas of <math>\triangle DBA</math> and <math>\triangle ACE</math> are equal. This common area is <math>\frac{m}{n}</math>, where <math>m</math> and <math>n</math> are relatively prime positive integers. Find <math>m+n</math>. | Circles <math>\mathcal{P}</math> and <math>\mathcal{Q}</math> have radii <math>1</math> and <math>4</math>, respectively, and are externally tangent at point <math>A</math>. Point <math>B</math> is on <math>\mathcal{P}</math> and point <math>C</math> is on <math>\mathcal{Q}</math> so that line <math>BC</math> is a common external tangent of the two circles. A line <math>\ell</math> through <math>A</math> intersects <math>\mathcal{P}</math> again at <math>D</math> and intersects <math>\mathcal{Q}</math> again at <math>E</math>. Points <math>B</math> and <math>C</math> lie on the same side of <math>\ell</math>, and the areas of <math>\triangle DBA</math> and <math>\triangle ACE</math> are equal. This common area is <math>\frac{m}{n}</math>, where <math>m</math> and <math>n</math> are relatively prime positive integers. Find <math>m+n</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <asy> | ||

| + | import cse5; | ||

| + | pathpen=black; pointpen=black; | ||

| + | size(6cm); | ||

| + | |||

| + | pair E = IP(L((-.2476,1.9689),(0.8,1.6),-3,5.5),CR((4,4),4)), D = (-.2476,1.9689); | ||

| + | |||

| + | filldraw(D--(0.8,1.6)--(0,0)--cycle,gray(0.7)); | ||

| + | filldraw(E--(0.8,1.6)--(4,0)--cycle,gray(0.7)); | ||

| + | D(CR((0,1),1)); D(CR((4,4),4,150,390)); | ||

| + | D(L(MP("D",D(D),N),MP("A",D((0.8,1.6)),NE),1,5.5)); | ||

| + | D((-1.2,0)--MP("B",D((0,0)),S)--MP("C",D((4,0)),S)--(8,0)); | ||

| + | D(MP("E",E,N)); | ||

| + | </asy> | ||

==Hint== | ==Hint== | ||

| − | + | <math>[ABC] = \frac{1}{2}ab \text{sin} C</math> is your friend for a quick solve. If you know about homotheties, go ahead, but you'll still need to do quite a bit of computation. If you're completely lost and you have a lot of time left in your mocking of this AIME, go ahead and use analytic geometry. | |

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 1 (guys trig is fast)== | ||

| + | Let <math>M</math> be the intersection of <math>\overline{BC}</math> and the common internal tangent of <math>\mathcal P</math> and <math>\mathcal Q.</math> We claim that <math>M</math> is the circumcenter of right <math>\triangle{ABC}.</math> Indeed, we have <math>AM = BM</math> and <math>BM = CM</math> by equal tangents to circles, and since <math>BM = CM, M</math> is the midpoint of <math>\overline{BC},</math> implying that <math>\angle{BAC} = 90.</math> Now draw <math>\overline{PA}, \overline{PB}, \overline{PM},</math> where <math>P</math> is the center of circle <math>\mathcal P.</math> Quadrilateral <math>PAMB</math> is cyclic, and by Pythagorean Theorem <math>PM = \sqrt{5},</math> so by Ptolemy on <math>PAMB</math> we have <cmath>AB \sqrt{5} = 2 \cdot 1 + 2 \cdot 1 = 4 \iff AB = \dfrac{4 \sqrt{5}}{5}.</cmath> Do the same thing on cyclic quadrilateral <math>QAMC</math> (where <math>Q</math> is the center of circle <math>\mathcal Q</math> and get <math>AC = \frac{8 \sqrt{5}}{5}.</math> | ||

| − | ==Solution | + | Let <math>\angle A = \angle{DAB}.</math> By Law of Sines, <math>BD = 2R \sin A = 2 \sin A.</math> Note that <math>\angle{D} = \angle{ABC}</math> from inscribed angles, so |

| + | <cmath>\begin{align*} | ||

| + | [ABD] &= \dfrac{1}{2} BD \cdot AB \cdot \sin{\angle B} \\ | ||

| + | &= \dfrac{1}{2} \cdot \dfrac{4 \sqrt{5}}{5} \cdot 2 \sin A \sin{\left(180 - \angle A - \angle D\right)} \\ | ||

| + | &= \dfrac{4 \sqrt{5}}{5} \cdot \sin A \cdot \sin{\left(\angle A + \angle D\right)} \\ | ||

| + | &= \dfrac{4 \sqrt{5}}{5} \cdot \sin A \cdot \left(\sin A \cos D + \cos A \sin D\right) \\ | ||

| + | &= \dfrac{4 \sqrt{5}}{5} \cdot \sin A \cdot \left(\sin A \cos{\angle{ABC}} + \cos A \sin{\angle{ABC}}\right) \\ | ||

| + | &= \dfrac{4 \sqrt{5}}{5} \cdot \sin A \cdot \left(\dfrac{\sqrt{5} \sin A}{5} + \dfrac{2 \sqrt{5} \cos A}{5}\right) \\ | ||

| + | &= \dfrac{4}{5} \cdot \sin A \left(\sin A + 2 \cos A\right) | ||

| + | \end{align*}</cmath> after angle addition identity. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Similarly, <math>\angle{EAC} = 90 - \angle A,</math> and by Law of Sines <math>CE = 8 \sin{\angle{EAC}} = 8 \cos A.</math> Note that <math>\angle{E} = \angle{ACB}</math> from inscribed angles, so | ||

| + | <cmath>\begin{align*} | ||

| + | [ACE] &= \dfrac{1}{2} AC \cdot CE \sin{\angle C} \\ | ||

| + | &= \dfrac{1}{2} \cdot \dfrac{8 \sqrt{5}}{5} \cdot 8 \cos A \sin{\left[180 - \left(90 - \angle A\right) - \angle E\right]} \\ | ||

| + | &= \dfrac{32 \sqrt{5}}{5} \cdot \cos A \sin{\left[\left(90 - \angle A\right) + \angle{ACB}\right]} \\ | ||

| + | &= \dfrac{32 \sqrt{5}}{5} \cdot \cos A \left(\dfrac{2 \sqrt{5} \cos A}{5} + \dfrac{\sqrt{5} \sin A}{5}\right) \\ | ||

| + | &= \dfrac{32}{5} \cdot \cos A \left(\sin A + 2 \cos A\right) | ||

| + | \end{align*}</cmath> after angle addition identity. | ||

| + | Setting the two areas equal, we get <cmath>\tan A = \frac{\sin A}{\cos A} = 8 \iff \sin A = \frac{8}{\sqrt{65}}, \cos A = \frac{1}{\sqrt{65}}</cmath> after Pythagorean Identity. Now plug back in and the common area is <math>\frac{64}{65} \iff \boxed{129}.</math> | ||

| + | |||

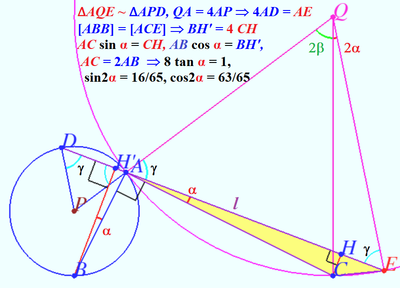

| + | ==Solution 2== | ||

<asy> | <asy> | ||

unitsize(35); | unitsize(35); | ||

| Line 17: | Line 56: | ||

dot(O_1);dot(O_2); | dot(O_1);dot(O_2); | ||

draw(rightanglemark(O_1,B,N,5));draw(rightanglemark(O_2,C,N,5));draw(C--L,dashed);draw(B--K,dashed);draw(C--Y);draw(B--X); | draw(rightanglemark(O_1,B,N,5));draw(rightanglemark(O_2,C,N,5));draw(C--L,dashed);draw(B--K,dashed);draw(C--Y);draw(B--X); | ||

| + | |||

</asy> | </asy> | ||

| − | Call <math>O_1</math> and <math>O_2</math> the centers of circles <math>\mathcal{P}</math> and <math>\mathcal{Q}</math>, respectively, and | + | Call <math>O_1</math> and <math>O_2</math> the centers of circles <math>\mathcal{P}</math> and <math>\mathcal{Q}</math>, respectively, and extend <math>CB</math> and <math>O_2O_1</math> to meet at point <math>N</math>. Call <math>K</math> and <math>L</math> the feet of the altitudes from <math>B</math> to <math>O_1N</math> and <math>C</math> to <math>O_2N</math>, respectively. Using the fact that <math>\triangle{O_1BN} \sim \triangle{O_2CN}</math> and setting <math>NO_1 = k</math>, we have that <math>\frac{k+5}{k} = \frac{4}{1} \implies k=\frac{5}{3}</math>. We can do some more length chasing using triangles similar to <math>O_1BN</math> to get that <math>AK = AL = \frac{24}{15}</math>, <math>BK = \frac{12}{15}</math>, and <math>CL = \frac{48}{15}</math>. Now, consider the circles <math>\mathcal{P}</math> and <math>\mathcal{Q}</math> on the coordinate plane, where <math>A</math> is the origin. If the line <math>\ell</math> through <math>A</math> intersects <math>\mathcal{P}</math> at <math>D</math> and <math>\mathcal{Q}</math> at <math>E</math> then <math>4 \cdot DA = AE</math>. To verify this, notice that <math>\triangle{AO_1D} \sim \triangle{EO_2A}</math> from the fact that both triangles are isosceles with <math>\angle{O_1AD} \cong \angle{O_2AE}</math>, which are corresponding angles. Since <math>O_2A = 4\cdot O_1A</math>, we can conclude that <math>4 \cdot DA = AE</math>. |

| − | Hence, we need to find the slope <math>m</math> of line <math>\ell</math> such that the perpendicular distance <math>n</math> from <math>B</math> to <math>AD</math> is four times the perpendicular distance <math>p</math> from <math>C</math> to <math>AE</math>. This will mean that the product of the bases and heights of triangles <math>ACE</math> and <math>DBA</math> will be equal, which in turn means that their areas will be equal. Let the line <math>\ell</math> have the equation <math>y = -mx \implies mx + y = 0</math> | + | Hence, we need to find the slope <math>m</math> of line <math>\ell</math> such that the perpendicular distance <math>n</math> from <math>B</math> to <math>AD</math> is four times the perpendicular distance <math>p</math> from <math>C</math> to <math>AE</math>. This will mean that the product of the bases and heights of triangles <math>ACE</math> and <math>DBA</math> will be equal, which in turn means that their areas will be equal. Let the line <math>\ell</math> have the equation <math>y = -mx \implies mx + y = 0</math>, and let <math>m</math> be a positive real number so that the negative slope of <math>\ell</math> is preserved. Setting <math>A = (0,0)</math>, the coordinates of <math>B</math> are <math>(x_B, y_B) = \left(\frac{-24}{15}, \frac{-12}{15}\right)</math>, and the coordinates of <math>C</math> are <math>(x_C, y_C) = \left(\frac{24}{15}, \frac{-48}{15}\right)</math>. Using the point-to-line distance formula and the condition <math>n = 4p</math>, we have <cmath>\frac{|mx_B + 1(y_B) + 0|}{\sqrt{m^2 + 1}} = \frac{4|mx_C + 1(y_C) + 0|}{\sqrt{m^2 + 1}}</cmath> <cmath>\implies |mx_B + y_B| = 4|mx_C + y_C| \implies \left|\frac{-24m}{15} + \frac{-12}{15}\right| = 4\left|\frac{24m}{15} + \frac{-48}{15}\right|.</cmath> If <math>m > 2</math>, then clearly <math>B</math> and <math>C</math> would not lie on the same side of <math>\ell</math>. Thus since <math>m > 0</math>, we must switch the signs of all terms in this equation when we get rid of the absolute value signs. We then have <cmath>\frac{6m}{15} + \frac{3}{15} = \frac{48}{15} - \frac{24m}{15} \implies 2m = 3 \implies m = \frac{3}{2}.</cmath> Thus, the equation of <math>\ell</math> is <math>y = -\frac{3}{2}x</math>. |

| − | Then we can find the coordinates of <math>D</math> by finding the point <math>(x,y)</math> other than <math>A = (0,0)</math> where the circle <math>\mathcal{P}</math> intersects <math>\ell</math>. <math>\mathcal{P}</math> can be represented with the equation <math>(x + 1)^2 + y^2 = 1</math>, and substituting <math>y = -\frac{3}{2}x</math> into this equation yields < | + | Then we can find the coordinates of <math>D</math> by finding the point <math>(x,y)</math> other than <math>A = (0,0)</math> where the circle <math>\mathcal{P}</math> intersects <math>\ell</math>. <math>\mathcal{P}</math> can be represented with the equation <math>(x + 1)^2 + y^2 = 1</math>, and substituting <math>y = -\frac{3}{2}x</math> into this equation yields <math>x = 0, -\frac{8}{13}</math> as solutions. Discarding <math>x = 0</math>, the <math>y</math>-coordinate of <math>D</math> is <math>-\frac{3}{2} \cdot -\frac{8}{13} = \frac{12}{13}</math>. The distance from <math>D</math> to <math>A</math> is then <math>\frac{4}{\sqrt{13}}.</math> The perpendicular distance from <math>B</math> to <math>AD</math> or the height of <math>\triangle{DBA}</math> is <math>\frac{|\frac{3}{2}\cdot\frac{-24}{15} + \frac{-12}{15} + 0|}{\sqrt{\frac{3}{2}^2 + 1}} = \frac{\frac{48}{15}}{\frac{\sqrt{13}}{2}} = \frac{32}{5\sqrt{13}}.</math> Finally, the common area is <math>\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{32}{5\sqrt{13}} \cdot \frac{4}{\sqrt{13}}\right) = \frac{64}{65}</math>, and <math>m + n = 64 + 65 = \boxed{129}</math>. |

| − | ==Solution | + | ==Solution 3== |

| − | By homothety, we deduce that <math>AE = 4 AD</math>. (The proof can also be executed by similar triangles formed from dropping perpendiculars from the centers of <math>P</math> and <math>Q</math> to <math>l</math>.) Therefore, our equality of area condition, or the equality of base times height condition, reduces to the fact that the distance from <math>B</math> to <math>l</math> is four times that from <math>C</math> to <math>l</math>. Let the distance from <math>C</math> be <math>x</math> and the distance from <math>B</math> be <math>4x</math>. | + | By [[homothety]], we deduce that <math>AE = 4 AD</math>. (The proof can also be executed by similar triangles formed from dropping perpendiculars from the centers of <math>P</math> and <math>Q</math> to <math>l</math>.) Therefore, our equality of area condition, or the equality of base times height condition, reduces to the fact that the distance from <math>B</math> to <math>l</math> is four times that from <math>C</math> to <math>l</math>. Let the distance from <math>C</math> be <math>x</math> and the distance from <math>B</math> be <math>4x</math>. |

| − | Let <math>P</math> and <math>Q</math> be the centers of their respective circles. Then dropping a perpendicular from <math>P</math> to <math>Q</math> creates a 3-4-5 right triangle, from which <math>BC = 4</math> and, if <math>\alpha = \angle{AQC}</math>, that <math>\cos \alpha = \dfrac{3}{5}</math>. Then <math>\angle{BPA} = 180^\circ - \alpha</math>, and the Law of Cosines on triangles <math>APB</math> and <math>AQC</math> gives <math>AB = \dfrac{4}{\sqrt{5}}</math> and <math>AC = \dfrac{8}{\sqrt{5}}.</math> | + | Let <math>P</math> and <math>Q</math> be the centers of their respective circles. Then dropping a perpendicular from <math>P</math> to <math>Q</math> creates a <math>3-4-5</math> right triangle, from which <math>BC = 4</math> and, if <math>\alpha = \angle{AQC}</math>, that <math>\cos \alpha = \dfrac{3}{5}</math>. Then <math>\angle{BPA} = 180^\circ - \alpha</math>, and the Law of Cosines on triangles <math>APB</math> and <math>AQC</math> gives <math>AB = \dfrac{4}{\sqrt{5}}</math> and <math>AC = \dfrac{8}{\sqrt{5}}.</math> |

Now, using the Pythagorean Theorem to express the length of the projection of <math>BC</math> onto line <math>l</math> gives | Now, using the Pythagorean Theorem to express the length of the projection of <math>BC</math> onto line <math>l</math> gives | ||

| − | <cmath>\sqrt{\frac{16}{5} - | + | <cmath>\sqrt{\frac{16}{5} - 16x^2} + \sqrt{\frac{64}{5} - x^2} = \sqrt{16 - 9x^2}.</cmath> |

Squaring and simplifying gives | Squaring and simplifying gives | ||

| − | <cmath>\sqrt{(\frac{1}{5} - x^2)(\frac{64}{5} - x^2)} = x^2,</cmath> | + | <cmath>\sqrt{\left(\frac{1}{5} - x^2\right)\left(\frac{64}{5} - x^2\right)} = x^2,</cmath> |

and squaring and solving gives <math>x = \dfrac{8}{5\sqrt{13}}.</math> | and squaring and solving gives <math>x = \dfrac{8}{5\sqrt{13}}.</math> | ||

| Line 42: | Line 82: | ||

But we know <math>\sin A = \dfrac{4x}{AB}</math>, and so a small computation gives <math>BD = \dfrac{16}{\sqrt{65}}.</math> The Pythagorean Theorem now gives | But we know <math>\sin A = \dfrac{4x}{AB}</math>, and so a small computation gives <math>BD = \dfrac{16}{\sqrt{65}}.</math> The Pythagorean Theorem now gives | ||

<cmath>AD = \sqrt{BD^2 - (4x)^2} + \sqrt{AB^2 - (4x)^2} = \frac{4}{\sqrt{13}},</cmath> | <cmath>AD = \sqrt{BD^2 - (4x)^2} + \sqrt{AB^2 - (4x)^2} = \frac{4}{\sqrt{13}},</cmath> | ||

| − | and so the common area is <math>\dfrac{1}{2} \cdot \frac{4}{\sqrt{13}} \cdot \frac{32}{\sqrt{13}} = \frac{64}{65}.</math> The answer is <math>\boxed{129}.</math> | + | and so the common area is <math>\dfrac{1}{2} \cdot \frac{4}{\sqrt{13}} \cdot \frac{32}{5\sqrt{13}} = \frac{64}{65}.</math> The answer is <math>\boxed{129}.</math> |

| + | |||

| + | ==Alternate Path to x== | ||

| + | Call the intersection of lines <math>l</math> and <math>BC</math> <math>E</math>.You can use similar triangles to find that the distance from <math>B</math> to <math>E</math> is four times the distance from <math>C</math> to <math>E</math>. Then draw a perpendicular from <math>A</math> to <math>BC</math> and call the point <math>F</math>. <math>AF = \frac{8}{5}</math> and <math>FE = FC + CE = \frac{16}{5} + \frac{4}{3} = \frac{68}{15}</math>, so by the Pythagorean Theorem, <math>AE = \dfrac{20\sqrt{13}}{5}</math>. You can now use similar triangles to find that <math>x = \dfrac{8}{5\sqrt{13}}</math> and continue on like in solution 2. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 4== | ||

| + | <math>DE</math> goes through <math>A</math>, the point of tangency of both circles. So <math>DE</math> intercepts equal arcs in circle <math>P</math> and <math>Q</math>: [[homothety]]. Hence, <math>AE=4AD</math>. We will use such similarity later. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The diagonal distance between the centers of the circles is <math>4+1=5</math>. The difference in heights is <math>4-1=3</math>. So <math>BC=\sqrt{5^2-3^2}=4</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The triangle connecting the centers with a side parallel to <math>BC</math> is a <math>3-4-5</math> right triangle. Since <math>O_PA=1</math>, the height of <math>A</math> is <math>1+3/5=8/5</math>. Drop an altitude from <math>A</math> to <math>BC</math> and call it <math>I</math>: <math>IB=4/5</math> and <math>IC=4-4/5=32/5</math>. Since right <math>\triangle AIB\sim\triangle CIB</math>, <math>ABC</math> is a right triangle also; <math>IB:IA:IC</math> form a geometric progression <math>\times 2</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Extend <math>BA</math> through <math>A</math> to a point <math>G</math> on the other side of <math>\circ Q</math>. By [[homothety]], <math>\triangle DAB\sim\triangle EAG</math>. By angle chasing <math>\triangle DAB</math> through right triangle <math>ABC</math>, we deduce that <math>\angle CEG</math> is a right angle. Since <math>ACEG</math> is cyclic, <math>\angle GAC</math> is also right. So <math>CG</math> is a diameter of <math>\circ G</math>. Because of this, <math>CG \perp BC</math>, the tangent line. <math>\triangle BCG</math> is right and <math>\triangle BCG\sim\triangle ABC\sim\triangle CAG</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <math>AC=\sqrt{(8/5)^2+(16/5)^2}=8\sqrt{5}/5</math> so <math>AG=2AC=16\sqrt{5}/5</math> and <math>[\triangle CAG]=64/5</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Since <math>[\triangle DAB]=[\triangle ACE]</math>, the common area is <math>[ACEG]/17</math>. <math>16[\triangle DAB]=[\triangle GAE]</math> because the triangles are similar with a ratio of <math>1:4</math>. So we only need to find <math>[\triangle CEG]</math> now. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Extend <math>DE</math> through <math>E</math> to intersect the tangent at <math>F</math>. Because <math>4DA=AE</math>, the altitude from <math>B</math> to <math>AD</math> is <math>4</math> times the height from <math>C</math> to <math>EA</math>. So <math>BC=3/4BF</math> and <math>BF=16/3</math>. We look at right triangle <math>\triangle AIF</math>. <math>IF=68/15</math> and <math>AI=8/5</math>. <math>\triangle AIF</math> is a <math>17-6-5\sqrt{13}</math> right triangle. Hypotenuse <math>AF</math> intersects <math>CG</math> at a point, we call it <math>H</math>. <math>CH=4/3\div 68/15\cdot 8/5=8/17</math>. So <math>HG=8-8/17=128/17</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | By [[Power of a Point Theorem|Power of a Point]], <math>CH\cdot HG=AH\cdot HE</math>. <math>AH=16/5\cdot 5\sqrt{13}/17=16\sqrt{13}/17.</math> So <math>HE=1024/289\cdot 17/(16\sqrt{13})=64/(17\sqrt{13})</math>. The height from <math>E</math> to <math>CG</math> is <math>17/(5\sqrt{13})\cdot 64/(17\sqrt{13})=64/65</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Thus, <math>[\triangle CEG]=64/65\cdot 8\div 2=256/65</math>. The area of the whole cyclic quadrilateral is <math>64/5+256/65=(832+256)/65=1088/65</math>. Lastly, the common area is <math>1/17</math> the area of the quadrilateral, or <math>64/65</math>. So <math>64+65=\boxed{129}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 5 (HARD computation)== | ||

| + | <asy> | ||

| + | unitsize(35); | ||

| + | draw(Circle((-1,0),1)); | ||

| + | draw(Circle((4,0),4)); | ||

| + | pair A,O_1, O_2, B,C,D,E,N,K,L,X,Y; | ||

| + | A=(0,0);O_1=(-1,0);O_2=(4,0);B=(-24/15,-12/15);D=(-8/13,12/13);E=(32/13,-48/13);C=(24/15,-48/15);N=extension(E,B,O_2,O_1);K=foot(B,O_1,N);L=foot(C,O_2,N);X=foot(B,A,D);Y=foot(C,E,A); | ||

| + | label("$A$",A,NE);label("$O_1$",O_1,NE);label("$O_2$",O_2,NE);label("$B$",B,SW);label("$C$",C,SW);label("$D$",D,NE);label("$E$",E,NE);label("$N$",N,W);label("$K$",(-24/15,0.2));label("$L$",(24/15,0.2));label("$n$",(-0.8,-0.12));label("$p$",((29/15,-48/15)));label("$\mathcal{P}$",(-1.6,1.1));label("$\mathcal{Q}$",(6,4)); | ||

| + | draw(A--B--D--cycle);draw(A--E--C--cycle);draw(C--N);draw(O_2--N);draw(O_1--B,dashed);draw(O_2--C,dashed); | ||

| + | dot(O_1);dot(O_2); | ||

| + | draw(rightanglemark(O_1,B,N,5));draw(rightanglemark(O_2,C,N,5)); | ||

| + | //draw(C--L,dashed);draw(B--K,dashed);draw(C--Y);draw(B--X); | ||

| + | path circle2 = Circle((4,0),4); | ||

| + | N = (-8/3,0); | ||

| + | pair X =rotate(180,O_2)*E; | ||

| + | pair Y = (8,0); | ||

| + | draw(X--Y,dashed); draw(E--Y,dashed);draw(E--X,dashed); draw(Y--C,dashed); draw(C--X,dashed); draw(O_2--Y); | ||

| + | dot("$X$", X, NE);dot("$Y$", Y, NE); | ||

| + | </asy> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Consider the homothety that takes triangle BDA onto CXY on the big circle, as plotted. Some hidden congruence angles are revealed which help reduce computation complexity. Just some angle chasing and straight forward trigs. Because <math>AE=XY</math> and <math>AE \parallel XY</math>, <math>XYE</math> is right angle. | ||

| + | |||

| + | First, <math>\frac{NO_1}{NO_1+5} = \frac{1}{4}</math>, so <math>NO_1=\frac{5}{3}</math>. And, | ||

| + | <cmath>\cos{\angle{AO_2C}}=\cos{2\angle{AYC}} = \frac{O_2C}{NO_1+5} = \frac{3}{5}</cmath> | ||

| + | <cmath>\sin{\angle{AYC}} = \sqrt{\dfrac{1-\cos{2\angle{AYC}}}{2}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}</cmath> | ||

| + | <cmath> \cos{\angle{AYC}} = \frac{2}{\sqrt{5}}</cmath> | ||

| + | Then, | ||

| + | <cmath>[AEC] = \frac{1}{2}AE*CE*\sin{\angle{ACE}}=\frac{1}{2}AE*8\sin{\angle{CYE}}*\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}</cmath> | ||

| + | <cmath>[CXY] = \frac{1}{2}CX*XY*\sin{\angle{CXY}}=\frac{1}{2}*8\sin{\angle{XYC}}*XY*\sin{\angle{CAY}}</cmath> | ||

| + | Since <math>\angle{CAY} = 90 - \angle{AYC}</math>, <math>\angle{XYC} = 90 - \angle{CYE}</math>, <math>XY = AE</math>, we have | ||

| + | <cmath>[CXY] = \frac{1}{2}*8AE\cos{\angle{CYE}}*\cos{\angle{AYC}}=\frac{1}{2}*8AE\cos{\angle{CYE}}*\frac{2}{\sqrt{5}}</cmath> | ||

| + | Since <math>\triangle{CXY}</math> is four times in scale to <math>\triangle{AEC}</math>, their area ratio is 16. Divide the two equations for the two areas, we have | ||

| + | <cmath>\tan{\angle{CYE}} = \frac{1}{8}</cmath> | ||

| + | With this angle found, everything else just follows. | ||

| + | <cmath>\sin{\angle{CYE}} = \dfrac{\tan{\angle{CYE}}}{\sqrt{1+\tan^2{\angle{CYE}}}}=\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{65}}</cmath> | ||

| + | <cmath>\cos{\angle{CYE}} = \dfrac{8}{\sqrt{65}}</cmath> | ||

| + | <cmath>\sin{\angle{AYE}} = \sin({\angle{AYC}+\angle{CYE}} )= \frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}*\frac{8}{\sqrt{65}} + \frac{2}{\sqrt{5}}*\frac{1}{\sqrt{65}} = \frac{2}{\sqrt{13}}</cmath> | ||

| + | <cmath>AE = 8\sin{\angle{AYE}} = \frac{16}{\sqrt{13}}</cmath> | ||

| + | <cmath>[AEC] = \frac{1}{2}*8*\frac{16}{\sqrt{13}}*\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{65}}*\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}=\frac{64}{65}</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 6 (Simple computation)== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Let <math>K</math> be the intersection of <math>BC</math> and <math>AE</math>. Since the radii of the two circles are 1:4, so we have <math>AD:AE=1:4</math>, and the distance from <math>B</math> to line <math>l</math> and the distance from <math>C</math> to line <math>l</math> are in a ratio of 4:1, so <math>BK:CK=4:1</math>. We can easily calculate the length of <math>BC</math> to be 4, so <math>CK=\frac{4}{3}</math>. Let <math>J</math> be the foot of perpendicular line from <math>A</math> to <math>BC</math>, we can know that <math>BJ:CJ=1:4</math>, so <math>BJ = 0.8</math>, <math>CJ=3.2</math>, <math>AJ=1.6</math>, and <math>AK=\sqrt{1.6^2+\left(3.2+\frac{4}{3}\right)^2}=\frac{4}{3}\sqrt{13}</math>. Since <math>CK^2 = EK\cdot AK</math>, so <math>EK=\frac{4}{39}\sqrt{13}</math>, and <math>AE = \frac{4}{3}\sqrt{13} - \frac{4}{39}\sqrt{13}= \frac{16}{13}\sqrt{13}</math>. <math>\sin\angle AKB=\frac{AJ}{AK} = \frac{1.6}{\frac{4}{3}\sqrt{13}}=\frac{1.2}{\sqrt{13}}</math>, so the distance from <math>C</math> to line <math>l</math> is <math>d=CK\cdot \sin\angle AKB = \frac{4}{3}\cdot \frac{1.2}{\sqrt{13}}=\frac{1.6}{\sqrt{13}}</math>. so the area is | ||

| + | <cmath> | ||

| + | [ACE] = \frac{1}{2}\cdot AE\cdot d = \frac{1}{2}\cdot\frac{16}{13}\sqrt{13}\frac{1.6}{\sqrt{13}} = \frac{64}{65} | ||

| + | </cmath> | ||

| + | The final answer is <math>\boxed{129}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | --- by Dan Li | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 7== | ||

| + | Consider the common tangent from <math>A</math> to both circles. Let this intersect <math>BC</math> at point <math>K</math>. From equal tangents, we have <math>BK=AK=CK</math>, which implies that <math>\angle BAC = 90^\circ</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Let the center of <math>\mathcal{P}</math> be <math>O_1</math>, and the center of <math>\mathcal{Q}</math> be <math>O_2</math>. Angle chasing, we find that <math>\triangle O_1DA \sim \triangle O_2EA</math> with a ratio of <math>1:4</math>. Hence <math>4AD = AE</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | We can easily deduce that <math>BC=4</math> by dropping an altitude from <math>O_1</math> to <math>O_2C</math>. Let <math>\angle ABC = \theta</math>. By some simple angle chasing, we obtain that <math>\angle BO_1A = 2\angle BDA = 2\angle ABC = 2\theta,</math> and similarly <math>\angle CO_2A = 180 - 2\theta</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Using LoC, we get that <math>AB = \sqrt{2-2\cos2\theta}</math> and <math>AC = \sqrt{32+32\cos2\theta}</math>. From Pythagorean theorem, we have <cmath>AB^2 + AC^2 = BC^2 \implies \cos 2\theta = -\frac{3}{5} \implies \cos \theta = \frac{1}{\sqrt5}, \sin \theta = \frac{2}{\sqrt 5}</cmath> | ||

| + | In other words, <math>AB = \frac{4}{\sqrt5}, AC = \frac{8}{\sqrt5}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Using the area condition, we have: | ||

| + | <cmath>\begin{align*} | ||

| + | \frac12 AD*AB \sin \angle DAB &= \frac 12 AE*AC \sin(90-\angle DAB) \\ | ||

| + | AD*\frac{4}{\sqrt5} \sin \angle DAB &= 4AD*\frac{8}{\sqrt5} \cos \angle DAB \\ | ||

| + | \sin \angle DAB &= 8 \cos \angle DAB \\ | ||

| + | \implies \sin \angle DAB &= \frac{8}{\sqrt{65}} | ||

| + | \end{align*}</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Now, for brevity, let <math>\angle D = \angle ADB</math> and <math>\angle A = \angle DAB</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | From Law of Sines on <math>\triangle ABD</math>, we have | ||

| + | <cmath>\begin{align*} | ||

| + | \frac{AB}{\sin \angle D} &= \frac{AD}{\sin (180-\angle A - \angle D)} \\ | ||

| + | \frac{\frac{4}{\sqrt5}}{\frac{2}{\sqrt5}} &= \frac{AD}{\sin \angle A \cos\angle D + \sin \angle D\cos\angle A} \\ | ||

| + | 2 &= \frac{AD}{\frac{2}{\sqrt{13}}} \\ | ||

| + | AD &= \frac{4}{\sqrt{13}} | ||

| + | \end{align*}</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | It remains to find the area of <math>\triangle ABD</math>. This is just <cmath>\frac12 AD*AB*\sin \angle A = \frac12 * \frac{4}{\sqrt{13}}*\frac{4}{\sqrt5}*\frac{8}{\sqrt{65}} = \frac{64}{65}</cmath> for an answer of <math>\boxed{129}.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | This solution was brought to you by Leonard_my_dude. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 8 (Synthetic-Trigonometry)== | ||

| + | Add in the line <math>k</math> as the internal tangent between the two circles. Let <math>M</math> be the midpoint of <math>BC</math>; It is well-known that <math>M</math> is on <math>k</math> and because <math>k</math> is the radical axis of the two circles, <math>AM=BM=CM</math>. Therefore because <math>M</math> is the circumcenter of <math>\triangle{BAC}</math>, <math>\angle{BAC}=90^{\circ}</math>. Let <math>O_P</math> be the center of circle <math>\mathcal{P}</math> and likewise let <math>O_Q</math> be the center of circle <math>\mathcal{Q}</math>. It is well known that by homothety <math>O_P, A,</math> and <math>O_Q</math> are collinear. It is well-known that <math>\angle{ABC}=\angle{ADB}=b</math>, and likewise <math>\angle{ACB}=\angle{AEC}=c</math>. By homothety, <math>AD=4AE</math>, therefore since the two triangles mentioned in the problem, the length of the altitude from <math>B</math> to <math>AD</math> is four times the length of the altitude from <math>C</math> to <math>AE</math>. Using the Pythagorean Theorem, <math>BC = 4</math>. By angle-chasing, <math>O_{P}AMB</math> is cyclic, and likewise <math>O_{Q}CMA</math> is cyclic. Use the Pythagorean Theorem for <math>\triangle{O_{P}BM}</math> to get <math>O_{P}M=\sqrt{5}</math>. Then by Ptolemy's Theorem <math>AB=\frac{4\sqrt{5}}{5} \implies AC=\frac{8\sqrt{5}}{5}</math>. Now to compute the area, using what we know about the length of the altitude from <math>B</math> to <math>AD</math> is four times the length of the altitude from <math>C</math> to <math>AE</math>, letting <math>x</math> be the length of the altitude from <math>C</math> to <math>AE</math>, <math>x=\frac{8}{5\sqrt{13}}</math>. From the Law of Sines, <math>\frac{BD}{\sin{A}}=2 \implies \sin{A}=\frac{4x}{AB} \implies BD=\frac{8x}{AB}=\frac{16\sqrt{65}}{65}</math>. Then use the Pythagorean Theorem twice and add up the lengths to get <math>AD=\frac{4}{\sqrt{13}}</math>. Use the formula <math>\frac{b \times h}{2}</math> to get <math>\frac{64}{65} = \boxed{129}</math> as the answer. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ~First | ||

| + | |||

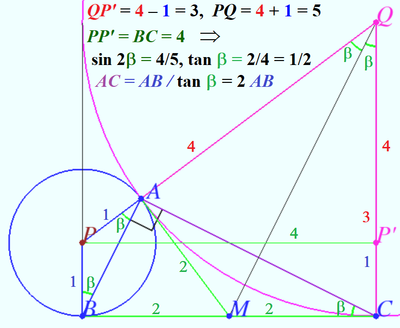

| + | ==Solution 9 (Visual)== | ||

| + | [[File:2015 AIME II 15.png|400px|right]] | ||

| + | [[File:2015 AIME II 15a.png|400px|right]] | ||

| + | Let <math>P</math> and <math>Q</math> be the centers of circles <math>\mathcal{P}</math> and <math>\mathcal{Q}</math> , respectively. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Let <math>M</math> be midpoint <math>BC, \beta = \angle ACB.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Upper diagram shows that | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>\sin 2\beta = \frac {4}{5}</math> and <math>AC = 2 AB.</math> Therefore <math>\cos 2\beta = \frac {3}{5}.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Let <math>CH\perp l, BH'\perp l.</math> Lower diagram shows that | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>\angle CAE = \angle ABH' = \alpha</math> (perpendicular sides) | ||

| + | |||

| + | and <math>\angle CQE = 2\alpha</math> (the same intersept <math>\overset{\Large\frown} {CE}).</math> | ||

| + | <cmath>\tan\alpha = \frac {1}{8}, | ||

| + | \sin2\alpha = \frac{2 \tan \alpha}{1 + \tan^2 \alpha} = \frac {16}{65}, | ||

| + | \cos2\alpha = \frac{1 - \tan^2 \alpha}{1 + \tan^2 \alpha} = \frac {63}{65}.</cmath> | ||

| + | The area | ||

| + | <cmath>[ACE] = [AQC]+[CQE]– [AQE].</cmath> | ||

| + | Hence <cmath>[ACE] =\frac{AQ^2}{2} \left(\sin 2\alpha + \sin 2\beta - \sin(2\alpha + 2\beta)\right),</cmath> | ||

| + | <cmath>[ACE] = | ||

| + | 8\left( \frac{16}{65}+\frac{4}{5} - \frac{4}{5}\cdot \frac{63}{65} - \frac{3}{5}\cdot \frac{16}{65}\right) = \frac{64}{65}\implies \boxed {129}.</cmath> | ||

| + | '''vladimir.shelomovskii@gmail.com, vvsss''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 10 (Similar Triangles, Angle Chasing, and Ptolemy's)== | ||

| + | We begin by extending <math>\overline{AB}</math> upwards until it intersects Circle <math>\mathcal{Q}</math>. We can call this point of intersection <math>F</math>. Connect <math>F</math> with <math>E</math>, <math>C</math>, and <math>A</math> for future use. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Create a trapezoid with points <math>B</math>, <math>C</math>, and the origins of Circles <math>\mathcal{P}</math> and <math>\mathcal{Q}</math>. After quick inspection, we can conclude that the distance between the origins is 5 and that <math>\overline{BC}</math> is 4. | ||

| + | |||

| + | (Note: It is important to understand that we could simply use the formula for the distance between the tangent points on a line and two different circles, which is <math>2\cdot \sqrt{a\cdot b}</math>, where <math>a</math> and <math>b</math> are the two respective radii of the circles. In our case, we get <math>2\cdot \sqrt{4} = 4</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Using similar triangles or homotheties, <math>AE=4\cdot AD</math> and <math>AF=4\cdot BA</math>. <math>BC^2 = BA\cdot BF</math>. <cmath>16 = BA\cdot (5\cdot BA)</cmath> <cmath>BA = \frac{4}{\sqrt{5}}</cmath> <cmath>AF = \frac{16}{\sqrt{5}}</cmath> <cmath>BF = 4\cdot \sqrt{5}</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Inspecting <math>\triangle{BFC}</math>, we recognize that it is a right triangle (<math>\angle{BCF} = 90</math>) as the final length (<math>\overline{FC}</math>) being 8 would allow for an <math>x-2x-x\sqrt{5}</math> triangle. Hence, the diameter of circle <math>\mathcal{Q}</math> = <math>CF</math>. This also means that <math>\angle{CAF} = \angle{CEF} = 90</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | From the fact that <math>\triangle{ABC}</math> is a right triangle: <cmath>AB^2 + AC^2 = BC^2</cmath> <cmath>AC = \frac{8}{\sqrt{5}}</cmath> | ||

| + | (Note: We could have also used <math>\triangle{FAC}</math>.) | ||

| + | |||

| + | Our next step is to start angle chasing to find any other similar triangles or shared angles. Label the intersection between <math>\overline{FC}</math> and <math>\overline{DE}</math> as <math>M</math>. Label <math>\angle{CAE} = \angle{CFE} = \theta</math>. Since <math>\angle{BAC} = 90</math>, <math>\angle{EAF} = \angle{DAB} = 90-\theta</math>. Now, use the sine formula and the fact that the areas of <math>\triangle{DBA}</math> and <math>\triangle{ACE}</math> are equal to get: | ||

| + | <cmath>\frac{1}{2}\cdot AC\cdot AE\cdot \sin{\theta} = \frac{1}{2}\cdot AD\cdot AB\cdot \sin{(90-\theta)}</cmath> | ||

| + | Since <math>\sin{(90-\theta)} = \cos{\theta}</math>: | ||

| + | <cmath>\tan{\theta} = \frac{AD}{2\cdot AE}</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Using right <math>\triangle{FCE}</math>, since <math>\angle{ACM} = \angle{CFE}</math>, <math>\tan{\theta} = \frac{CE}{FE}</math>. Hence, plugging into the previous equation: | ||

| + | <cmath>\frac{CE}{FE} = \frac{AD}{2\cdot AE}</cmath> | ||

| + | Using the Pythagorean theorem on <math>\triangle{FCE}</math>, <math>FE = \sqrt{(64 - CE^2)}</math>. We also know that <math>AE=4\cdot AD</math> | ||

| + | Plugging back in: | ||

| + | <cmath>\frac{CE}{\sqrt{(64 - CE^2)}} = \frac{AD}{2\cdot (4\cdot AD)}</cmath> | ||

| + | <cmath>\frac{CE}{\sqrt{(64 - CE^2)}} = \frac{1}{8}</cmath>. | ||

| + | From here, we can square both sides and bring everything to one side to get: | ||

| + | <cmath>EF^2 + 64EF - 64 = 0</cmath>. | ||

| + | <cmath>EF = \frac{64}{\sqrt{65}}</cmath> | ||

| + | <cmath>CE = \frac{8}{\sqrt{65}}</cmath> | ||

| + | We should also return to the fact that <math>\sin{\theta} = \frac{CE}{CF}</math> from <math>\triangle{FCE}</math>, so <cmath>\sin{\theta} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{65}}</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | From the fact that <math>\angle{CAF} = \angle{CEF} = 90</math>, we can use Ptolemy's Theorem on quadrilateral <math>ACEF</math>. <math>AC\cdot EF + CE\cdot FA = CF\cdot AE</math>. Plugging in and solving, we get that <math>AE = \frac{16}{\sqrt{13}}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | We now have all of our pieces to use the Sine Formula on <math>\triangle{ACE}</math>. <cmath>\frac{1}{2}\cdot AC\cdot AF\cdot \sin{\theta}</cmath> | ||

| + | <cmath>\frac{1}{2}\cdot \frac{8}{\sqrt{5}}\cdot \frac{16}{\sqrt{13}}\cdot \frac{1}{\sqrt{65}} = \frac{64}{65} = \boxed {129}</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ~Solution by: armang32324 | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 11 (Trig)== | ||

| + | Let the center of the larger circle be <math>O,</math> and the center of the smaller circle be <math>P.</math> It is not hard to find the areas of <math>ACO</math> and <math>ABP</math> using pythagorean theorem, which are <math>\frac{32}{5}</math> and <math>\frac{2}{5}</math> respectively. Assign <math>\angle AOC=a,\angle COE=c,\angle DPB=d,\angle BPA=b.</math> We can figure out that <math>\angle AOE=\angle DOA=\theta</math> using vertical angles and isosceles triangles. Now, using <math>[ABC]=\frac{1}{2}ab\sin C</math> | ||

| + | <cmath>[ACE]=[AOC]+[COE]-[AOC]=\dfrac{32}{5}-8\sin c-8\sin \theta,</cmath> | ||

| + | <cmath>[DAB]=[APD]+[APB]+[BPD]=\dfrac{2}{5}+\dfrac{1}{2}\sin \theta+\dfrac{1}{2}\sin d.</cmath> | ||

| + | We can also figure out that <math>\sin a=\dfrac{4}{5},\cos a=\dfrac{3}{5},\sin b=\dfrac{4}{5}, \cos b=-\dfrac{3}{5}.</math> Also, <math>c=\theta-a</math> and <math>d=360-\theta-b.</math> Using sum and difference identities: | ||

| + | <cmath>\sin c=\dfrac{3}{5}\sin \theta-\dfrac{4}{5}\cos \theta,</cmath> | ||

| + | <cmath>\sin d=\dfrac{3}{5}\sin\theta-\dfrac{4}{5}\cos\theta.</cmath> | ||

| + | (We can also notice that <math>c+d=360-\theta-b+\theta-a=360-(a+b)=180</math> which means that <math>\sin c=\sin d.</math>) | ||

| + | Substituting in the equations for <math>\sin c</math> and <math>\sin d</math> into the equations for <math>[ACE]</math> and <math>[DAB],</math> setting them equal, and simplifying: | ||

| + | <cmath>3=2\sin\theta+3\cos\theta.</cmath> | ||

| + | Solving this equation we get that <math>\sin\theta=\frac{12}{13}</math> and <math>\cos\theta=\frac{5}{13}.</math> Doing a lot of substitution gives us <cmath>[ACE]=[DAB]=\dfrac{64}{65},</cmath> which means the answer is <math>64+65=\boxed{129}.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ~[[BS2012]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Video Solution== | ||

| + | https://youtu.be/LBCmQc2awMk | ||

| + | |||

| + | ~MathProblemSolvingSkills.com | ||

| + | |||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

{{AIME box|year=2015|n=II|num-b=14|after=Last Problem}} | {{AIME box|year=2015|n=II|num-b=14|after=Last Problem}} | ||

{{MAA Notice}} | {{MAA Notice}} | ||

Latest revision as of 18:15, 20 December 2023

Contents

- 1 Problem

- 2 Hint

- 3 Solution 1 (guys trig is fast)

- 4 Solution 2

- 5 Solution 3

- 6 Alternate Path to x

- 7 Solution 4

- 8 Solution 5 (HARD computation)

- 9 Solution 6 (Simple computation)

- 10 Solution 7

- 11 Solution 8 (Synthetic-Trigonometry)

- 12 Solution 9 (Visual)

- 13 Solution 10 (Similar Triangles, Angle Chasing, and Ptolemy's)

- 14 Solution 11 (Trig)

- 15 Video Solution

- 16 See also

Problem

Circles ![]() and

and ![]() have radii

have radii ![]() and

and ![]() , respectively, and are externally tangent at point

, respectively, and are externally tangent at point ![]() . Point

. Point ![]() is on

is on ![]() and point

and point ![]() is on

is on ![]() so that line

so that line ![]() is a common external tangent of the two circles. A line

is a common external tangent of the two circles. A line ![]() through

through ![]() intersects

intersects ![]() again at

again at ![]() and intersects

and intersects ![]() again at

again at ![]() . Points

. Points ![]() and

and ![]() lie on the same side of

lie on the same side of ![]() , and the areas of

, and the areas of ![]() and

and ![]() are equal. This common area is

are equal. This common area is ![]() , where

, where ![]() and

and ![]() are relatively prime positive integers. Find

are relatively prime positive integers. Find ![]() .

.

![[asy] import cse5; pathpen=black; pointpen=black; size(6cm); pair E = IP(L((-.2476,1.9689),(0.8,1.6),-3,5.5),CR((4,4),4)), D = (-.2476,1.9689); filldraw(D--(0.8,1.6)--(0,0)--cycle,gray(0.7)); filldraw(E--(0.8,1.6)--(4,0)--cycle,gray(0.7)); D(CR((0,1),1)); D(CR((4,4),4,150,390)); D(L(MP("D",D(D),N),MP("A",D((0.8,1.6)),NE),1,5.5)); D((-1.2,0)--MP("B",D((0,0)),S)--MP("C",D((4,0)),S)--(8,0)); D(MP("E",E,N)); [/asy]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/6/b/7/6b7782afc839b219809c6266cec4abca23e9d026.png)

Hint

![]() is your friend for a quick solve. If you know about homotheties, go ahead, but you'll still need to do quite a bit of computation. If you're completely lost and you have a lot of time left in your mocking of this AIME, go ahead and use analytic geometry.

is your friend for a quick solve. If you know about homotheties, go ahead, but you'll still need to do quite a bit of computation. If you're completely lost and you have a lot of time left in your mocking of this AIME, go ahead and use analytic geometry.

Solution 1 (guys trig is fast)

Let ![]() be the intersection of

be the intersection of ![]() and the common internal tangent of

and the common internal tangent of ![]() and

and ![]() We claim that

We claim that ![]() is the circumcenter of right

is the circumcenter of right ![]() Indeed, we have

Indeed, we have ![]() and

and ![]() by equal tangents to circles, and since

by equal tangents to circles, and since ![]() is the midpoint of

is the midpoint of ![]() implying that

implying that ![]() Now draw

Now draw ![]() where

where ![]() is the center of circle

is the center of circle ![]() Quadrilateral

Quadrilateral ![]() is cyclic, and by Pythagorean Theorem

is cyclic, and by Pythagorean Theorem ![]() so by Ptolemy on

so by Ptolemy on ![]() we have

we have ![]() Do the same thing on cyclic quadrilateral

Do the same thing on cyclic quadrilateral ![]() (where

(where ![]() is the center of circle

is the center of circle ![]() and get

and get ![]()

Let ![]() By Law of Sines,

By Law of Sines, ![]() Note that

Note that ![]() from inscribed angles, so

from inscribed angles, so

![\begin{align*} [ABD] &= \dfrac{1}{2} BD \cdot AB \cdot \sin{\angle B} \\ &= \dfrac{1}{2} \cdot \dfrac{4 \sqrt{5}}{5} \cdot 2 \sin A \sin{\left(180 - \angle A - \angle D\right)} \\ &= \dfrac{4 \sqrt{5}}{5} \cdot \sin A \cdot \sin{\left(\angle A + \angle D\right)} \\ &= \dfrac{4 \sqrt{5}}{5} \cdot \sin A \cdot \left(\sin A \cos D + \cos A \sin D\right) \\ &= \dfrac{4 \sqrt{5}}{5} \cdot \sin A \cdot \left(\sin A \cos{\angle{ABC}} + \cos A \sin{\angle{ABC}}\right) \\ &= \dfrac{4 \sqrt{5}}{5} \cdot \sin A \cdot \left(\dfrac{\sqrt{5} \sin A}{5} + \dfrac{2 \sqrt{5} \cos A}{5}\right) \\ &= \dfrac{4}{5} \cdot \sin A \left(\sin A + 2 \cos A\right) \end{align*}](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/c/3/a/c3a05b76c76b1a9f0e7b0e6efd3502533396daff.png) after angle addition identity.

after angle addition identity.

Similarly, ![]() and by Law of Sines

and by Law of Sines ![]() Note that

Note that ![]() from inscribed angles, so

from inscribed angles, so

![\begin{align*} [ACE] &= \dfrac{1}{2} AC \cdot CE \sin{\angle C} \\ &= \dfrac{1}{2} \cdot \dfrac{8 \sqrt{5}}{5} \cdot 8 \cos A \sin{\left[180 - \left(90 - \angle A\right) - \angle E\right]} \\ &= \dfrac{32 \sqrt{5}}{5} \cdot \cos A \sin{\left[\left(90 - \angle A\right) + \angle{ACB}\right]} \\ &= \dfrac{32 \sqrt{5}}{5} \cdot \cos A \left(\dfrac{2 \sqrt{5} \cos A}{5} + \dfrac{\sqrt{5} \sin A}{5}\right) \\ &= \dfrac{32}{5} \cdot \cos A \left(\sin A + 2 \cos A\right) \end{align*}](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/c/2/4/c24fe39373ba10e834a5e13acdffe0caa1add903.png) after angle addition identity.

Setting the two areas equal, we get

after angle addition identity.

Setting the two areas equal, we get ![]() after Pythagorean Identity. Now plug back in and the common area is

after Pythagorean Identity. Now plug back in and the common area is ![]()

Solution 2

![[asy] unitsize(35); draw(Circle((-1,0),1)); draw(Circle((4,0),4)); pair A,O_1, O_2, B,C,D,E,N,K,L,X,Y; A=(0,0);O_1=(-1,0);O_2=(4,0);B=(-24/15,-12/15);D=(-8/13,12/13);E=(32/13,-48/13);C=(24/15,-48/15);N=extension(E,B,O_2,O_1);K=foot(B,O_1,N);L=foot(C,O_2,N);X=foot(B,A,D);Y=foot(C,E,A); label("$A$",A,NE);label("$O_1$",O_1,NE);label("$O_2$",O_2,NE);label("$B$",B,SW);label("$C$",C,SW);label("$D$",D,NE);label("$E$",E,NE);label("$N$",N,W);label("$K$",(-24/15,0.2));label("$L$",(24/15,0.2));label("$n$",(-0.8,-0.12));label("$p$",((29/15,-48/15)));label("$\mathcal{P}$",(-1.6,1.1));label("$\mathcal{Q}$",(6,4)); draw(A--B--D--cycle);draw(A--E--C--cycle);draw(C--N);draw(O_2--N);draw(O_1--B,dashed);draw(O_2--C,dashed); dot(O_1);dot(O_2); draw(rightanglemark(O_1,B,N,5));draw(rightanglemark(O_2,C,N,5));draw(C--L,dashed);draw(B--K,dashed);draw(C--Y);draw(B--X); [/asy]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/a/7/8/a7802557b0402d026b6cf9218388bd0561ac27e4.png)

Call ![]() and

and ![]() the centers of circles

the centers of circles ![]() and

and ![]() , respectively, and extend

, respectively, and extend ![]() and

and ![]() to meet at point

to meet at point ![]() . Call

. Call ![]() and

and ![]() the feet of the altitudes from

the feet of the altitudes from ![]() to

to ![]() and

and ![]() to

to ![]() , respectively. Using the fact that

, respectively. Using the fact that ![]() and setting

and setting ![]() , we have that

, we have that ![]() . We can do some more length chasing using triangles similar to

. We can do some more length chasing using triangles similar to ![]() to get that

to get that ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . Now, consider the circles

. Now, consider the circles ![]() and

and ![]() on the coordinate plane, where

on the coordinate plane, where ![]() is the origin. If the line

is the origin. If the line ![]() through

through ![]() intersects

intersects ![]() at

at ![]() and

and ![]() at

at ![]() then

then ![]() . To verify this, notice that

. To verify this, notice that ![]() from the fact that both triangles are isosceles with

from the fact that both triangles are isosceles with ![]() , which are corresponding angles. Since

, which are corresponding angles. Since ![]() , we can conclude that

, we can conclude that ![]() .

.

Hence, we need to find the slope ![]() of line

of line ![]() such that the perpendicular distance

such that the perpendicular distance ![]() from

from ![]() to

to ![]() is four times the perpendicular distance

is four times the perpendicular distance ![]() from

from ![]() to

to ![]() . This will mean that the product of the bases and heights of triangles

. This will mean that the product of the bases and heights of triangles ![]() and

and ![]() will be equal, which in turn means that their areas will be equal. Let the line

will be equal, which in turn means that their areas will be equal. Let the line ![]() have the equation

have the equation ![]() , and let

, and let ![]() be a positive real number so that the negative slope of

be a positive real number so that the negative slope of ![]() is preserved. Setting

is preserved. Setting ![]() , the coordinates of

, the coordinates of ![]() are

are ![]() , and the coordinates of

, and the coordinates of ![]() are

are ![]() . Using the point-to-line distance formula and the condition

. Using the point-to-line distance formula and the condition ![]() , we have

, we have ![]()

![]() If

If ![]() , then clearly

, then clearly ![]() and

and ![]() would not lie on the same side of

would not lie on the same side of ![]() . Thus since

. Thus since ![]() , we must switch the signs of all terms in this equation when we get rid of the absolute value signs. We then have

, we must switch the signs of all terms in this equation when we get rid of the absolute value signs. We then have ![]() Thus, the equation of

Thus, the equation of ![]() is

is ![]() .

.

Then we can find the coordinates of ![]() by finding the point

by finding the point ![]() other than

other than ![]() where the circle

where the circle ![]() intersects

intersects ![]() .

. ![]() can be represented with the equation

can be represented with the equation ![]() , and substituting

, and substituting ![]() into this equation yields

into this equation yields ![]() as solutions. Discarding

as solutions. Discarding ![]() , the

, the ![]() -coordinate of

-coordinate of ![]() is

is ![]() . The distance from

. The distance from ![]() to

to ![]() is then

is then ![]() The perpendicular distance from

The perpendicular distance from ![]() to

to ![]() or the height of

or the height of ![]() is

is  Finally, the common area is

Finally, the common area is ![]() , and

, and ![]() .

.

Solution 3

By homothety, we deduce that ![]() . (The proof can also be executed by similar triangles formed from dropping perpendiculars from the centers of

. (The proof can also be executed by similar triangles formed from dropping perpendiculars from the centers of ![]() and

and ![]() to

to ![]() .) Therefore, our equality of area condition, or the equality of base times height condition, reduces to the fact that the distance from

.) Therefore, our equality of area condition, or the equality of base times height condition, reduces to the fact that the distance from ![]() to

to ![]() is four times that from

is four times that from ![]() to

to ![]() . Let the distance from

. Let the distance from ![]() be

be ![]() and the distance from

and the distance from ![]() be

be ![]() .

.

Let ![]() and

and ![]() be the centers of their respective circles. Then dropping a perpendicular from

be the centers of their respective circles. Then dropping a perpendicular from ![]() to

to ![]() creates a

creates a ![]() right triangle, from which

right triangle, from which ![]() and, if

and, if ![]() , that

, that ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() , and the Law of Cosines on triangles

, and the Law of Cosines on triangles ![]() and

and ![]() gives

gives ![]() and

and ![]()

Now, using the Pythagorean Theorem to express the length of the projection of ![]() onto line

onto line ![]() gives

gives

![]() Squaring and simplifying gives

Squaring and simplifying gives

![\[\sqrt{\left(\frac{1}{5} - x^2\right)\left(\frac{64}{5} - x^2\right)} = x^2,\]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/4/b/e/4be7cbd9d9e569e4adac0a37f5f01b4ab68a2b9f.png) and squaring and solving gives

and squaring and solving gives ![]()

By the Law of Sines on triangle ![]() , we have

, we have

![]() But we know

But we know ![]() , and so a small computation gives

, and so a small computation gives ![]() The Pythagorean Theorem now gives

The Pythagorean Theorem now gives

![]() and so the common area is

and so the common area is ![]() The answer is

The answer is ![]()

Alternate Path to x

Call the intersection of lines ![]() and

and ![]()

![]() .You can use similar triangles to find that the distance from

.You can use similar triangles to find that the distance from ![]() to

to ![]() is four times the distance from

is four times the distance from ![]() to

to ![]() . Then draw a perpendicular from

. Then draw a perpendicular from ![]() to

to ![]() and call the point

and call the point ![]() .

. ![]() and

and ![]() , so by the Pythagorean Theorem,

, so by the Pythagorean Theorem, ![]() . You can now use similar triangles to find that

. You can now use similar triangles to find that ![]() and continue on like in solution 2.

and continue on like in solution 2.

Solution 4

![]() goes through

goes through ![]() , the point of tangency of both circles. So

, the point of tangency of both circles. So ![]() intercepts equal arcs in circle

intercepts equal arcs in circle ![]() and

and ![]() : homothety. Hence,

: homothety. Hence, ![]() . We will use such similarity later.

. We will use such similarity later.

The diagonal distance between the centers of the circles is ![]() . The difference in heights is

. The difference in heights is ![]() . So

. So ![]() .

.

The triangle connecting the centers with a side parallel to ![]() is a

is a ![]() right triangle. Since

right triangle. Since ![]() , the height of

, the height of ![]() is

is ![]() . Drop an altitude from

. Drop an altitude from ![]() to

to ![]() and call it

and call it ![]() :

: ![]() and

and ![]() . Since right

. Since right ![]() ,

, ![]() is a right triangle also;

is a right triangle also; ![]() form a geometric progression

form a geometric progression ![]() .

.

Extend ![]() through

through ![]() to a point

to a point ![]() on the other side of

on the other side of ![]() . By homothety,

. By homothety, ![]() . By angle chasing

. By angle chasing ![]() through right triangle

through right triangle ![]() , we deduce that

, we deduce that ![]() is a right angle. Since

is a right angle. Since ![]() is cyclic,

is cyclic, ![]() is also right. So

is also right. So ![]() is a diameter of

is a diameter of ![]() . Because of this,

. Because of this, ![]() , the tangent line.

, the tangent line. ![]() is right and

is right and ![]() .

.

![]() so

so ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Since ![]() , the common area is

, the common area is ![]() .

. ![]() because the triangles are similar with a ratio of

because the triangles are similar with a ratio of ![]() . So we only need to find

. So we only need to find ![]() now.

now.

Extend ![]() through

through ![]() to intersect the tangent at

to intersect the tangent at ![]() . Because

. Because ![]() , the altitude from

, the altitude from ![]() to

to ![]() is

is ![]() times the height from

times the height from ![]() to

to ![]() . So

. So ![]() and

and ![]() . We look at right triangle

. We look at right triangle ![]() .

. ![]() and

and ![]() .

. ![]() is a

is a ![]() right triangle. Hypotenuse

right triangle. Hypotenuse ![]() intersects

intersects ![]() at a point, we call it

at a point, we call it ![]() .

. ![]() . So

. So ![]() .

.

By Power of a Point, ![]() .

. ![]() So

So ![]() . The height from

. The height from ![]() to

to ![]() is

is ![]() .

.

Thus, ![]() . The area of the whole cyclic quadrilateral is

. The area of the whole cyclic quadrilateral is ![]() . Lastly, the common area is

. Lastly, the common area is ![]() the area of the quadrilateral, or

the area of the quadrilateral, or ![]() . So

. So ![]() .

.

Solution 5 (HARD computation)

![[asy] unitsize(35); draw(Circle((-1,0),1)); draw(Circle((4,0),4)); pair A,O_1, O_2, B,C,D,E,N,K,L,X,Y; A=(0,0);O_1=(-1,0);O_2=(4,0);B=(-24/15,-12/15);D=(-8/13,12/13);E=(32/13,-48/13);C=(24/15,-48/15);N=extension(E,B,O_2,O_1);K=foot(B,O_1,N);L=foot(C,O_2,N);X=foot(B,A,D);Y=foot(C,E,A); label("$A$",A,NE);label("$O_1$",O_1,NE);label("$O_2$",O_2,NE);label("$B$",B,SW);label("$C$",C,SW);label("$D$",D,NE);label("$E$",E,NE);label("$N$",N,W);label("$K$",(-24/15,0.2));label("$L$",(24/15,0.2));label("$n$",(-0.8,-0.12));label("$p$",((29/15,-48/15)));label("$\mathcal{P}$",(-1.6,1.1));label("$\mathcal{Q}$",(6,4)); draw(A--B--D--cycle);draw(A--E--C--cycle);draw(C--N);draw(O_2--N);draw(O_1--B,dashed);draw(O_2--C,dashed); dot(O_1);dot(O_2); draw(rightanglemark(O_1,B,N,5));draw(rightanglemark(O_2,C,N,5)); //draw(C--L,dashed);draw(B--K,dashed);draw(C--Y);draw(B--X); path circle2 = Circle((4,0),4); N = (-8/3,0); pair X =rotate(180,O_2)*E; pair Y = (8,0); draw(X--Y,dashed); draw(E--Y,dashed);draw(E--X,dashed); draw(Y--C,dashed); draw(C--X,dashed); draw(O_2--Y); dot("$X$", X, NE);dot("$Y$", Y, NE); [/asy]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/8/8/f/88ff40209a59d89779ce1c7281eb1f46ed44526f.png)

Consider the homothety that takes triangle BDA onto CXY on the big circle, as plotted. Some hidden congruence angles are revealed which help reduce computation complexity. Just some angle chasing and straight forward trigs. Because ![]() and

and ![]() ,

, ![]() is right angle.

is right angle.

First, ![]() , so

, so ![]() . And,

. And,

![]()

![]()

![]() Then,

Then,

![]()

![]() Since

Since ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , we have

, we have

![]() Since

Since ![]() is four times in scale to

is four times in scale to ![]() , their area ratio is 16. Divide the two equations for the two areas, we have

, their area ratio is 16. Divide the two equations for the two areas, we have

![]() With this angle found, everything else just follows.

With this angle found, everything else just follows.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Solution 6 (Simple computation)

Let ![]() be the intersection of

be the intersection of ![]() and

and ![]() . Since the radii of the two circles are 1:4, so we have

. Since the radii of the two circles are 1:4, so we have ![]() , and the distance from

, and the distance from ![]() to line

to line ![]() and the distance from

and the distance from ![]() to line

to line ![]() are in a ratio of 4:1, so

are in a ratio of 4:1, so ![]() . We can easily calculate the length of

. We can easily calculate the length of ![]() to be 4, so

to be 4, so ![]() . Let

. Let ![]() be the foot of perpendicular line from

be the foot of perpendicular line from ![]() to

to ![]() , we can know that

, we can know that ![]() , so

, so ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and  . Since

. Since ![]() , so

, so ![]() , and

, and ![]() .

. ![]() , so the distance from

, so the distance from ![]() to line

to line ![]() is

is ![]() . so the area is

. so the area is

![]() The final answer is

The final answer is ![]() .

.

--- by Dan Li

Solution 7

Consider the common tangent from ![]() to both circles. Let this intersect

to both circles. Let this intersect ![]() at point

at point ![]() . From equal tangents, we have

. From equal tangents, we have ![]() , which implies that

, which implies that ![]() .

.

Let the center of ![]() be

be ![]() , and the center of

, and the center of ![]() be

be ![]() . Angle chasing, we find that

. Angle chasing, we find that ![]() with a ratio of

with a ratio of ![]() . Hence

. Hence ![]() .

.

We can easily deduce that ![]() by dropping an altitude from

by dropping an altitude from ![]() to

to ![]() . Let

. Let ![]() . By some simple angle chasing, we obtain that

. By some simple angle chasing, we obtain that ![]() and similarly

and similarly ![]() .

.

Using LoC, we get that ![]() and

and ![]() . From Pythagorean theorem, we have

. From Pythagorean theorem, we have ![]() In other words,

In other words, ![]() .

.

Using the area condition, we have:

Now, for brevity, let ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

From Law of Sines on ![]() , we have

, we have

It remains to find the area of ![]() . This is just

. This is just ![]() for an answer of

for an answer of ![]()

This solution was brought to you by Leonard_my_dude.

Solution 8 (Synthetic-Trigonometry)

Add in the line ![]() as the internal tangent between the two circles. Let

as the internal tangent between the two circles. Let ![]() be the midpoint of

be the midpoint of ![]() ; It is well-known that

; It is well-known that ![]() is on

is on ![]() and because

and because ![]() is the radical axis of the two circles,

is the radical axis of the two circles, ![]() . Therefore because

. Therefore because ![]() is the circumcenter of

is the circumcenter of ![]() ,

, ![]() . Let

. Let ![]() be the center of circle

be the center of circle ![]() and likewise let

and likewise let ![]() be the center of circle

be the center of circle ![]() . It is well known that by homothety

. It is well known that by homothety ![]() and

and ![]() are collinear. It is well-known that

are collinear. It is well-known that ![]() , and likewise

, and likewise ![]() . By homothety,

. By homothety, ![]() , therefore since the two triangles mentioned in the problem, the length of the altitude from

, therefore since the two triangles mentioned in the problem, the length of the altitude from ![]() to

to ![]() is four times the length of the altitude from

is four times the length of the altitude from ![]() to

to ![]() . Using the Pythagorean Theorem,

. Using the Pythagorean Theorem, ![]() . By angle-chasing,

. By angle-chasing, ![]() is cyclic, and likewise

is cyclic, and likewise ![]() is cyclic. Use the Pythagorean Theorem for

is cyclic. Use the Pythagorean Theorem for ![]() to get

to get ![]() . Then by Ptolemy's Theorem

. Then by Ptolemy's Theorem ![]() . Now to compute the area, using what we know about the length of the altitude from

. Now to compute the area, using what we know about the length of the altitude from ![]() to

to ![]() is four times the length of the altitude from

is four times the length of the altitude from ![]() to

to ![]() , letting

, letting ![]() be the length of the altitude from

be the length of the altitude from ![]() to

to ![]() ,

, ![]() . From the Law of Sines,

. From the Law of Sines, ![]() . Then use the Pythagorean Theorem twice and add up the lengths to get

. Then use the Pythagorean Theorem twice and add up the lengths to get ![]() . Use the formula

. Use the formula ![]() to get

to get ![]() as the answer.

as the answer.

~First

Solution 9 (Visual)

Let ![]() and

and ![]() be the centers of circles

be the centers of circles ![]() and

and ![]() , respectively.

, respectively.

Let ![]() be midpoint

be midpoint ![]()

Upper diagram shows that

![]() and

and ![]() Therefore

Therefore ![]()

Let ![]() Lower diagram shows that

Lower diagram shows that

![]() (perpendicular sides)

(perpendicular sides)

and ![]() (the same intersept

(the same intersept ![]()

![]() The area

The area

![]() Hence

Hence ![]()

![]() vladimir.shelomovskii@gmail.com, vvsss

vladimir.shelomovskii@gmail.com, vvsss

Solution 10 (Similar Triangles, Angle Chasing, and Ptolemy's)

We begin by extending ![]() upwards until it intersects Circle

upwards until it intersects Circle ![]() . We can call this point of intersection

. We can call this point of intersection ![]() . Connect

. Connect ![]() with

with ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() for future use.

for future use.

Create a trapezoid with points ![]() ,

, ![]() , and the origins of Circles

, and the origins of Circles ![]() and

and ![]() . After quick inspection, we can conclude that the distance between the origins is 5 and that

. After quick inspection, we can conclude that the distance between the origins is 5 and that ![]() is 4.

is 4.

(Note: It is important to understand that we could simply use the formula for the distance between the tangent points on a line and two different circles, which is ![]() , where

, where ![]() and

and ![]() are the two respective radii of the circles. In our case, we get

are the two respective radii of the circles. In our case, we get ![]() .

.

Using similar triangles or homotheties, ![]() and

and ![]() .

. ![]() .

. ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Inspecting ![]() , we recognize that it is a right triangle (

, we recognize that it is a right triangle (![]() ) as the final length (

) as the final length (![]() ) being 8 would allow for an

) being 8 would allow for an ![]() triangle. Hence, the diameter of circle

triangle. Hence, the diameter of circle ![]() =

= ![]() . This also means that

. This also means that ![]() .

.

From the fact that ![]() is a right triangle:

is a right triangle: ![]()

![]() (Note: We could have also used

(Note: We could have also used ![]() .)

.)

Our next step is to start angle chasing to find any other similar triangles or shared angles. Label the intersection between ![]() and

and ![]() as

as ![]() . Label

. Label ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() ,

, ![]() . Now, use the sine formula and the fact that the areas of

. Now, use the sine formula and the fact that the areas of ![]() and

and ![]() are equal to get:

are equal to get:

![]() Since

Since ![]() :

:

![]()

Using right ![]() , since

, since ![]() ,

, ![]() . Hence, plugging into the previous equation:

. Hence, plugging into the previous equation:

![]() Using the Pythagorean theorem on

Using the Pythagorean theorem on ![]() ,

, ![]() . We also know that

. We also know that ![]() Plugging back in:

Plugging back in:

![]()

![]() .

From here, we can square both sides and bring everything to one side to get:

.

From here, we can square both sides and bring everything to one side to get:

![]() .

.

![]()

![]() We should also return to the fact that

We should also return to the fact that ![]() from

from ![]() , so

, so ![]()

From the fact that ![]() , we can use Ptolemy's Theorem on quadrilateral

, we can use Ptolemy's Theorem on quadrilateral ![]() .

. ![]() . Plugging in and solving, we get that

. Plugging in and solving, we get that ![]() .

.

We now have all of our pieces to use the Sine Formula on ![]() .

. ![]()

![]()

~Solution by: armang32324

Solution 11 (Trig)

Let the center of the larger circle be ![]() and the center of the smaller circle be

and the center of the smaller circle be ![]() It is not hard to find the areas of

It is not hard to find the areas of ![]() and

and ![]() using pythagorean theorem, which are

using pythagorean theorem, which are ![]() and

and ![]() respectively. Assign

respectively. Assign ![]() We can figure out that

We can figure out that ![]() using vertical angles and isosceles triangles. Now, using

using vertical angles and isosceles triangles. Now, using ![]()

![]()

![]() We can also figure out that

We can also figure out that ![]() Also,

Also, ![]() and

and ![]() Using sum and difference identities:

Using sum and difference identities:

![]()

![]() (We can also notice that

(We can also notice that ![]() which means that

which means that ![]() )

Substituting in the equations for

)

Substituting in the equations for ![]() and

and ![]() into the equations for

into the equations for ![]() and

and ![]() setting them equal, and simplifying:

setting them equal, and simplifying:

![]() Solving this equation we get that

Solving this equation we get that ![]() and

and ![]() Doing a lot of substitution gives us

Doing a lot of substitution gives us ![]() which means the answer is

which means the answer is ![]()

Video Solution

~MathProblemSolvingSkills.com

See also

| 2015 AIME II (Problems • Answer Key • Resources) | ||

| Preceded by Problem 14 |

Followed by Last Problem | |

| 1 • 2 • 3 • 4 • 5 • 6 • 7 • 8 • 9 • 10 • 11 • 12 • 13 • 14 • 15 | ||

| All AIME Problems and Solutions | ||

The problems on this page are copyrighted by the Mathematical Association of America's American Mathematics Competitions.