Difference between revisions of "2005 AMC 10A Problems/Problem 20"

(→Solution 2) |

Sravya m18 (talk | contribs) (→Solution 2) |

||

| (12 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

==Problem== | ==Problem== | ||

| − | An | + | An equilangular octagon has four sides of length <math>1</math> and four sides of length <math>\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}</math>, arranged so that no two consecutive sides have the same length. What is the area of the octagon? |

| − | <math> \ | + | <math> \textbf{(A) } \frac72\qquad \textbf{(B) } \frac{7\sqrt2}{2}\qquad \textbf{(C) } \frac{5+4\sqrt2}{2}\qquad \textbf{(D) } \frac{4+5\sqrt2}{2}\qquad \textbf{(E) } 7 </math> |

==Solution 1== | ==Solution 1== | ||

| − | The area of the octagon can be divided up into 5 squares with side <math>\frac{\sqrt2}2</math> and 4 right triangles, which are half the area of each of the squares. | + | The area of the octagon can be divided up into <math>5</math> squares with side <math>\frac{\sqrt2}2</math> and <math>4</math> right triangles, which are half the area of each of the squares. |

Therefore, the area of the octagon is equal to the area of <math>5+4\left(\frac12\right)=7</math> squares. | Therefore, the area of the octagon is equal to the area of <math>5+4\left(\frac12\right)=7</math> squares. | ||

| − | The area of each square is <math>\left(\frac{\sqrt2}2\right)^2=\frac12</math>, so the area of 7 squares is <math>\ | + | The area of each square is <math>\left(\frac{\sqrt2}2\right)^2=\frac12</math>, so the area of <math>7</math> squares is <math>\boxed{\textbf{(A) }\frac72}</math>. |

<asy> pair A=(0.5, 0), B=(0, 0.5), C=(0, 1.5), D=(0.5, 2), E=(1.5, 2), F=(2, 1.5), G=(2, 0.5), H=(1.5, 0); draw(A--B); draw(B--C); draw(C--D); draw(D--E);draw(E--F);draw(F--G); draw(G--H); draw(H--A);draw(A--F, blue);draw(E--B,blue);draw(C--H, blue); draw(D--G,blue);dot(A);dot(B);dot(C);dot(D);dot(E);dot(F);dot(G);dot(H); </asy> | <asy> pair A=(0.5, 0), B=(0, 0.5), C=(0, 1.5), D=(0.5, 2), E=(1.5, 2), F=(2, 1.5), G=(2, 0.5), H=(1.5, 0); draw(A--B); draw(B--C); draw(C--D); draw(D--E);draw(E--F);draw(F--G); draw(G--H); draw(H--A);draw(A--F, blue);draw(E--B,blue);draw(C--H, blue); draw(D--G,blue);dot(A);dot(B);dot(C);dot(D);dot(E);dot(F);dot(G);dot(H); </asy> | ||

==Solution 2== | ==Solution 2== | ||

| − | Using the diagram from above, we can extend the sides of length <math>1</math> to form four right triangles and the octagon, all inside a square. The right triangles are 45-45-90 triangles with hypotenuse <math>\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}</math>, so the side length is <math>\frac{1}{2}</math>. Thus, the area of the larger square is <math>2 \cdot 2 = 4</math>, and the area of the four right triangles combined is <math>\frac{1}{2}</math>, so the area of the octagon is <math>\frac{ | + | Using the diagram from above, we can extend the sides of length <math>1</math> to form four right triangles and the octagon, all inside a square. If you wanted, you could also extend the sides of length <math>\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}</math> and get the same answer, but that would make things slightly harder. The right triangles are <math>45-45-90</math> triangles with hypotenuse <math>\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}</math>, so the side length is <math>\frac{1}{2}</math>. Thus, the area of the larger square is <math>2 \cdot 2 = 4</math>, and the area of the four right triangles combined is <math>\frac{1}{2}</math>, so the area of the octagon is <math>4-\frac{1}{2}=\boxed{\textbf{(A) }\frac{7}{2}}</math> |

| + | edited by mobius247 | ||

| + | ==Solution 3== | ||

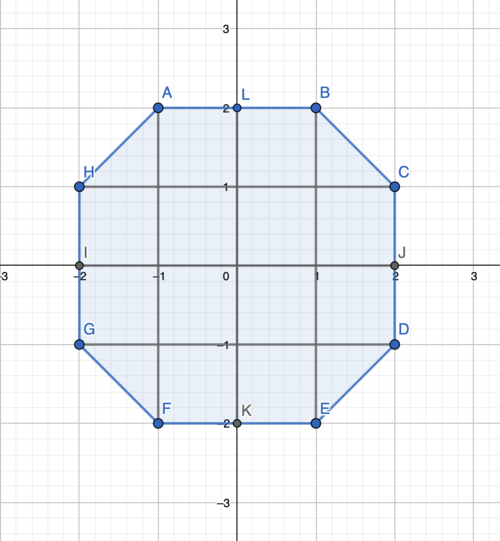

| + | Refer to the following diagram: | ||

| − | <math> | + | [[File:AMC10_2005A_P20.png|500px]] |

| − | <math> | + | |

| + | (Picture made on Geogebra) | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Note that each square has area <math>\frac14</math>, and each triangle has area <math>\frac18</math>. The total area is <math>12\cdot\frac14+4\cdot\frac18=\frac72 \Longrightarrow \boxed{\textbf{(A) } \frac72}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Remark: This solution requires careful drawing, and also realising that connecting lines leads to squares and isosceles right triangles (notice the <math>\sqrt{2}</math> and realise that it is the hypotenuse of a <math>45-45-90</math> triangle with side length ratios <math>1:1:\sqrt{2}</math>.). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ~JH. L | ||

==Video Solution== | ==Video Solution== | ||

Revision as of 15:58, 2 June 2024

Problem

An equilangular octagon has four sides of length ![]() and four sides of length

and four sides of length ![]() , arranged so that no two consecutive sides have the same length. What is the area of the octagon?

, arranged so that no two consecutive sides have the same length. What is the area of the octagon?

![]()

Solution 1

The area of the octagon can be divided up into ![]() squares with side

squares with side ![]() and

and ![]() right triangles, which are half the area of each of the squares.

right triangles, which are half the area of each of the squares.

Therefore, the area of the octagon is equal to the area of ![]() squares.

squares.

The area of each square is  , so the area of

, so the area of ![]() squares is

squares is ![]() .

.

![[asy] pair A=(0.5, 0), B=(0, 0.5), C=(0, 1.5), D=(0.5, 2), E=(1.5, 2), F=(2, 1.5), G=(2, 0.5), H=(1.5, 0); draw(A--B); draw(B--C); draw(C--D); draw(D--E);draw(E--F);draw(F--G); draw(G--H); draw(H--A);draw(A--F, blue);draw(E--B,blue);draw(C--H, blue); draw(D--G,blue);dot(A);dot(B);dot(C);dot(D);dot(E);dot(F);dot(G);dot(H); [/asy]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/c/5/5/c555a9225f3304367b0d7f6c435ec5293f27dff4.png)

Solution 2

Using the diagram from above, we can extend the sides of length ![]() to form four right triangles and the octagon, all inside a square. If you wanted, you could also extend the sides of length

to form four right triangles and the octagon, all inside a square. If you wanted, you could also extend the sides of length ![]() and get the same answer, but that would make things slightly harder. The right triangles are

and get the same answer, but that would make things slightly harder. The right triangles are ![]() triangles with hypotenuse

triangles with hypotenuse ![]() , so the side length is

, so the side length is ![]() . Thus, the area of the larger square is

. Thus, the area of the larger square is ![]() , and the area of the four right triangles combined is

, and the area of the four right triangles combined is ![]() , so the area of the octagon is

, so the area of the octagon is ![]()

edited by mobius247

Solution 3

Refer to the following diagram:

(Picture made on Geogebra)

Note that each square has area ![]() , and each triangle has area

, and each triangle has area ![]() . The total area is

. The total area is ![]() .

.

Remark: This solution requires careful drawing, and also realising that connecting lines leads to squares and isosceles right triangles (notice the ![]() and realise that it is the hypotenuse of a

and realise that it is the hypotenuse of a ![]() triangle with side length ratios

triangle with side length ratios ![]() .).

.).

~JH. L

Video Solution

CHECK OUT Video Solution: https://youtu.be/rwPFZnYk9V8

See Also

| 2005 AMC 10A (Problems • Answer Key • Resources) | ||

| Preceded by Problem 19 |

Followed by Problem 21 | |

| 1 • 2 • 3 • 4 • 5 • 6 • 7 • 8 • 9 • 10 • 11 • 12 • 13 • 14 • 15 • 16 • 17 • 18 • 19 • 20 • 21 • 22 • 23 • 24 • 25 | ||

| All AMC 10 Problems and Solutions | ||

The problems on this page are copyrighted by the Mathematical Association of America's American Mathematics Competitions.