Difference between revisions of "2017 AIME I Problems/Problem 15"

Icematrix2 (talk | contribs) |

Boxtheanswer (talk | contribs) m (→Solution 2) |

||

| (44 intermediate revisions by 13 users not shown) | |||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

==Solution 1== | ==Solution 1== | ||

| − | + | Lemma: If <math>x,y</math> satisfy <math>px+qy=1</math>, then the minimal value of <math>\sqrt{x^2+y^2}</math> is <math>\frac{1}{\sqrt{p^2+q^2}}</math>. | |

Proof: Recall that the distance between the point <math>(x_0,y_0)</math> and the line <math>px+qy+r = 0</math> is given by <math>\frac{|px_0+qy_0+r|}{\sqrt{p^2+q^2}}</math>. In particular, the distance between the origin and any point <math>(x,y)</math> on the line <math>px+qy=1</math> is at least <math>\frac{1}{\sqrt{p^2+q^2}}</math>. | Proof: Recall that the distance between the point <math>(x_0,y_0)</math> and the line <math>px+qy+r = 0</math> is given by <math>\frac{|px_0+qy_0+r|}{\sqrt{p^2+q^2}}</math>. In particular, the distance between the origin and any point <math>(x,y)</math> on the line <math>px+qy=1</math> is at least <math>\frac{1}{\sqrt{p^2+q^2}}</math>. | ||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

--- | --- | ||

| − | Let the vertices of the right triangle be <math>(0,0),(5,0),(0,2\sqrt{3}),</math> and let <math>(a,0),(0,b)</math> be the two vertices of the equilateral triangle on the legs of the right triangle. Then, the third vertex of the equilateral triangle is <math>\left(\frac{a+\sqrt{3} | + | Let the vertices of the right triangle be <math>(0,0),(5,0),(0,2\sqrt{3}),</math> and let <math>(a,0),(0,b)</math> be the two vertices of the equilateral triangle on the legs of the right triangle. Then, the third vertex of the equilateral triangle is <math>\left(\frac{a+b\sqrt{3}}{2},\frac{a\sqrt{3}+b}{2}\right)</math>. This point must lie on the hypotenuse <math>\frac{x}{5} + \frac{y}{2\sqrt{3}} = 1</math>, i.e. <math>a,b</math> must satisfy |

| − | <cmath> \frac{a+\sqrt{3} | + | <cmath> \frac{a+b\sqrt{3}}{10}+\frac{a\sqrt{3}+b}{4\sqrt{3}} = 1,</cmath> |

which can be simplified to | which can be simplified to | ||

<cmath>\frac{7}{20}a + \frac{11\sqrt{3}}{60}b = 1.</cmath> | <cmath>\frac{7}{20}a + \frac{11\sqrt{3}}{60}b = 1.</cmath> | ||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

and hence the answer is <math>75+3+67=\boxed{145}</math>. | and hence the answer is <math>75+3+67=\boxed{145}</math>. | ||

| − | ==Solution 2 | + | ==Solution 2== |

| − | Let <math> | + | Let <math>AB=2\sqrt{3}, BC=5</math>, <math>D</math> lies on <math>BC</math>, <math>F</math> lies on <math>AB</math> and <math>E</math> lies on <math>AC</math> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Set <math>D</math> as the origin, <math>BD=a,BF=b</math>, <math>F</math> can be expressed as <math>-a+bi</math> in argand plane, the distance of <math>CD</math> is <math>5-a</math> | |

| − | |||

| − | < | ||

| − | |||

| − | < | ||

| − | |||

| − | < | ||

| − | < | + | We know that <math>(-a+bi)\cdot\cos(-\frac{\pi}{3})=(-\frac{a+\sqrt{3}b}{2}+\frac{\sqrt{3}a+b}{2}i)</math>. We know that the slope of <math>AC</math> is <math>-\frac{2\sqrt{3}}{5}</math>, we have that <math>\frac{5-a-(-\frac{a+\sqrt{3}b}{2})}{(\sqrt{3}a+b)/2}=\frac{5}{2\sqrt{3}}</math>, after computation, we have <math>11b+7\sqrt{3}a=20\sqrt{3}</math> |

| − | Now | + | Now the rest is easy with C-S inequality, <math>(a^2+b^2)(147+121)\geq (7\sqrt{3}a+11b)^2, a^2+b^2\geq \frac{300}{67}</math> so the smallest area is <math>\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}\cdot \frac{300}{67}=\frac{75\sqrt{3}}{67}</math>, and the answer is <math>\boxed{145}</math> |

| − | + | ~bluesoul | |

== Solution 3 == | == Solution 3 == | ||

| Line 93: | Line 73: | ||

- Awsomness2000 | - Awsomness2000 | ||

| − | == Solution 4 == | + | ==Solution 4 (Trigonometry)== |

| + | [[File:2017 AIME I 15.png|530px|right]] | ||

| + | Let <math>ED = DF = x, AC = 5, \angle BAC = \alpha, \angle CDE = \beta. </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Then <math>\cot \alpha = \frac {5}{2\sqrt{3}},\angle CDF = \beta - 60^\circ,</math> | ||

| + | <cmath>\angle AED = \beta - \alpha, CD = x \cos(\beta - 60^\circ).</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | By Law of Sines on triangle <math>\triangle ADE</math> we get | ||

| + | <cmath>AD = x \frac {\sin (\beta – \alpha)}{\sin{\alpha}}.</cmath> | ||

| + | <cmath>AD + CD = AC \implies </cmath> | ||

| + | <cmath>x(\frac {\sin \beta}{\tan{\alpha}} - \cos \beta) +x (\frac {\cos\beta}{2} +\frac{\sin\beta \sqrt{3}}{2}) = AC</cmath> | ||

| + | <cmath> \implies \frac{AC}{x} = \sin \beta (\cot \alpha + \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2})- \frac{\cos\beta}{2} </cmath> | ||

| + | <cmath>a \sin \beta + b \cos \beta \le \sqrt {a^2+b^2} \implies</cmath> | ||

| + | <cmath>\frac{AC}{x} \le \sqrt {\left(\cot \alpha + \frac {\sqrt3}{2}\right)^2 + \left(\frac {1}{2}\right)^2} = \sqrt {\cot^2 \alpha + \sqrt {3} \cot \alpha + 1}</cmath> | ||

| + | The smallest area <math>[DEF]</math> is | ||

| + | <cmath>\frac {\sqrt {3}}{4} \cdot x_{min}^2 = \frac {\sqrt {3} AC^2}{4 (\cot ^2 \alpha + \sqrt {3} \cot \alpha + 1)} = \frac{75 \sqrt{3}}{67}.</cmath> | ||

| + | '''vladimir.shelomovskii@gmail.com, vvsss''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Note=== | ||

| + | <math>a \sin \beta + b \cos \beta \le \sqrt {a^2+b^2}</math> follows from Cauchy-Schwarz. | ||

| + | <cmath>a \sin \beta + b \cos \beta \le \sqrt{a^2+b^2}\sqrt{\sin^2+\cos^2}=\sqrt{a^2+b^2}</cmath> | ||

| + | ~mathboy282 | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Solution 5 (Complex numbers)== | ||

We will use complex numbers. Set the vertex at the right angle to be the origin, and set the axes so the other two vertices are <math>5</math> and <math>2\sqrt{3}i</math>, respectively. Now let the vertex of the equilateral triangle on the real axis be <math>a</math> and let the vertex of the equilateral triangle on the imaginary axis be <math>bi</math>. Then, the third vertex of the equilateral triangle is given by: | We will use complex numbers. Set the vertex at the right angle to be the origin, and set the axes so the other two vertices are <math>5</math> and <math>2\sqrt{3}i</math>, respectively. Now let the vertex of the equilateral triangle on the real axis be <math>a</math> and let the vertex of the equilateral triangle on the imaginary axis be <math>bi</math>. Then, the third vertex of the equilateral triangle is given by: | ||

| − | <cmath>(bi-a)e^{-\frac{\pi}{3}i}+a=(bi-a)(\frac{1}{2}-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}i)+a=(\frac{a}{2}+\frac{b\sqrt{3}}{2})+(\frac{a\sqrt{3}}{2}+\frac{ | + | <cmath>(bi-a)e^{-\frac{\pi}{3}i}+a=(bi-a)(\frac{1}{2}-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}i)+a=(\frac{a}{2}+\frac{b\sqrt{3}}{2})+(\frac{a\sqrt{3}}{2}+\frac{b}{2})i</cmath>. |

For this to be on the hypotenuse of the right triangle, we also have the following: | For this to be on the hypotenuse of the right triangle, we also have the following: | ||

| Line 105: | Line 108: | ||

Thus, the minimum we seek is simply <math>\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}\cdot\frac{1200}{268}=\frac{75\sqrt{3}}{67}</math>, so the desired answer is <math>\boxed{145}</math>. | Thus, the minimum we seek is simply <math>\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}\cdot\frac{1200}{268}=\frac{75\sqrt{3}}{67}</math>, so the desired answer is <math>\boxed{145}</math>. | ||

| − | == Solution | + | == Solution 6== |

In the complex plane, let the vertices of the triangle be <math>a = 5,</math> <math>b = 2i \sqrt{3},</math> and <math>c = 0.</math> Let <math>e</math> be one of the vertices, where <math>e</math> is real. A point on the line passing through <math>a = 5</math> and <math>b = 2i \sqrt{3}</math> can be expressed in the form | In the complex plane, let the vertices of the triangle be <math>a = 5,</math> <math>b = 2i \sqrt{3},</math> and <math>c = 0.</math> Let <math>e</math> be one of the vertices, where <math>e</math> is real. A point on the line passing through <math>a = 5</math> and <math>b = 2i \sqrt{3}</math> can be expressed in the form | ||

<cmath>f = (1 - t) a + tb = 5(1 - t) + 2ti \sqrt{3}.</cmath>We want the third vertex <math>d</math> to lie on the line through <math>b</math> and <math>c,</math> which is the imaginary axis, so its real part is 0. | <cmath>f = (1 - t) a + tb = 5(1 - t) + 2ti \sqrt{3}.</cmath>We want the third vertex <math>d</math> to lie on the line through <math>b</math> and <math>c,</math> which is the imaginary axis, so its real part is 0. | ||

| − | Since the small triangle is equilateral, <math>d - e = \ | + | Since the small triangle is equilateral, <math>d - e = \cos 60^\circ \cdot (f - e),</math> or |

<cmath>d - e = \frac{1 + i \sqrt{3}}{2} \cdot (5(1 - t) - e + 2ti \sqrt{3}).</cmath>Then the real part of <math>d</math> is | <cmath>d - e = \frac{1 + i \sqrt{3}}{2} \cdot (5(1 - t) - e + 2ti \sqrt{3}).</cmath>Then the real part of <math>d</math> is | ||

<cmath>\frac{5(1 - t) - e}{2} - 3t + e = 0.</cmath>Solving for <math>t</math> in terms of <math>e,</math> we find | <cmath>\frac{5(1 - t) - e}{2} - 3t + e = 0.</cmath>Solving for <math>t</math> in terms of <math>e,</math> we find | ||

| Line 120: | Line 123: | ||

<cmath>\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4} \cdot \frac{300}{67} = \boxed{\frac{75 \sqrt{3}}{67}}.</cmath> | <cmath>\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4} \cdot \frac{300}{67} = \boxed{\frac{75 \sqrt{3}}{67}}.</cmath> | ||

| − | ==Solution | + | ==Solution 7== |

| − | Employ the same complex bash as in Solution | + | We can use complex numbers. Set the origin at the right angle. Let the point on the real axis be <math>a</math> and the point on the imaginary axis be <math>bi</math>. Then, we see that <math>(a-bi)\left(\text{cis}\frac{\pi}{3}\right)+bi=(a-bi)\left(\frac{1}{2}+i\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)+bi=\left(\frac{1}{2}a+\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}b\right)+i\left(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}a+\frac{1}{2}b\right).</math> Now we switch back to Cartesian coordinates. The equation of the hypotenuse is <math>y=-\frac{2\sqrt{3}}{5}x+2\sqrt{3}.</math> This means that the point <math>\left(\frac{1}{2}a+\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}b,\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}a+\frac{1}{2}b\right)</math> is on the line. Plugging the numbers in, we have <math>\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}a+\frac{1}{2}b=-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{5}a-\frac{3}{5}b+2\sqrt{3} \implies 7\sqrt{3}a+11b=20\sqrt{3}.</math> Now, we note that the side length of the equilateral triangle is <math>a^2+b^2</math> so it suffices to minimize that. By Cauchy-Schwarz, we have <math>(a^2+b^2)(147+121)\geq(7\sqrt{3}a+11b)^2 \implies (a^2+b^2)\geq\frac{300}{67}.</math> Thus, the area of the smallest triangle is <math>\frac{300}{67}\cdot\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}=\frac{75\sqrt{3}}{67}</math> so our desired answer is <math>\boxed{145}</math>. |

| + | |||

| + | (Solution by Pleaseletmetwin, but not added to the Wiki by Pleaseletmetwin) | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 8== | ||

| + | Employ the same complex bash as in Solution 5, but instead note that minimizing <math>x^2+y^2</math> is the same as minimizing the distance from | ||

0,0 to x,y, since they are the same quantity. We use point to plane instead, which gives you the required distance. | 0,0 to x,y, since they are the same quantity. We use point to plane instead, which gives you the required distance. | ||

| − | ==Solution | + | ==Solution 9 (Non Analytic)== |

| − | We | + | |

| + | Let <math>S</math> be the triangle with side lengths <math>2\sqrt{3},~5,</math> and <math>\sqrt{37}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | We will think about this problem backwards, by constructing a triangle as large as possible (We will call it <math>T</math>, for convenience) which is similar to <math>S</math> with vertices outside of a unit equilateral triangle <math>\triangle ABC</math>, such that each vertex of the equilateral triangle lies on a side of <math>T</math>. After we find the side lengths of <math>T</math>, we will use ratios to trace back towards the original problem. | ||

| + | |||

| + | First of all, let <math>\theta = 90^{\circ}</math>, <math>\alpha = \arctan\left(\frac{2\sqrt{3}}{5}\right)</math>, and <math>\beta = \arctan\left(\frac{5}{2\sqrt{3}}\right)</math> (These three angles are simply the angles of triangle <math>S</math>; out of these three angles, <math>\alpha</math> is the smallest angle, and <math>\theta</math> is the largest angle). Then let us consider a point <math>P</math> inside <math>\triangle ABC</math> such that <math>\angle APB = 180^{\circ} - \theta</math>, <math>\angle BPC = 180^{\circ} - \alpha</math>, and <math>\angle APC = 180^{\circ} - \beta</math>. Construct the circumcircles <math>\omega_{AB}, ~\omega_{BC},</math> and <math>\omega_{AC}</math> of triangles <math>APB, ~BPC,</math> and <math>APC</math> respectively. | ||

| + | |||

| + | From here, we will prove the lemma that if we choose points <math>X</math>, <math>Y</math>, and <math>Z</math> on circumcircles <math>\omega_{AB}, ~\omega_{BC},</math> and <math>\omega_{AC}</math> respectively such that <math>X</math>, <math>B</math>, and <math>Y</math> are collinear and <math>Y</math>, <math>C</math>, and <math>Z</math> are collinear, then <math>Z</math>, <math>A</math>, and <math>X</math> must be collinear. First of all, if we let <math>\angle PAX = m</math>, then <math>\angle PBX = 180^{\circ} - m</math> (by the properties of cyclic quadrilaterals), <math>\angle PBY = m</math> (by adjacent angles), <math>\angle PCY = 180^{\circ} - m</math> (by cyclic quadrilaterals), <math>\angle PCZ = m</math> (adjacent angles), and <math>\angle PAZ = 180^{\circ} - m</math> (cyclic quadrilaterals). Since <math>\angle PAX</math> and <math>\angle PAZ</math> are supplementary, <math>Z</math>, <math>A</math>, and <math>X</math> are collinear as desired. Hence, <math>\triangle XYZ</math> has an inscribed equilateral triangle <math>ABC</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In addition, now we know that all triangles <math>XYZ</math> (as described above) must be similar to triangle <math>S</math>, as <math>\angle AXB = \theta</math> and <math>\angle BYC = \alpha</math>, so we have developed <math>AA</math> similarity between the two triangles. Thus, <math>\triangle XYZ</math> is the triangle similar to <math>S</math> which we were desiring. Our goal now is to maximize the length of <math>XY</math>, in order to maximize the area of <math>XYZ</math>, to achieve our original goal. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Note that, all triangles <math>PYX</math> are similar to each other if <math>Y</math>, <math>B</math>, and <math>X</math> are collinear. This is because <math>\angle PYB</math> is constant, and <math>\angle PXB</math> is also a constant value. Then we have <math>AA</math> similarity between this set of triangles. To maximize <math>XY</math>, we can instead maximize <math>PY</math>, which is simply the diameter of <math>\omega_{BC}</math>. From there, we can determine that <math>\angle PBY = 90^{\circ}</math>, and with similar logic, <math>PA</math>, <math>PB</math>, and <math>PC</math> are perpendicular to <math>ZX</math>, <math>XY</math>, and <math>YZ</math> respectively We have found our desired largest possible triangle <math>T</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | All we have to do now is to calculate <math>YZ</math>, and use ratios from similar triangles to determine the side length of the equilateral triangle inscribed within <math>S</math>. First of all, we will prove that <math>\angle ZPY = \angle ACB + \angle AXB</math>. By the properties of cyclic quadrilaterals, <math>\angle AXB = \angle PAB + \angle PBA</math>, which means that <math>\angle ACB + \angle AXB = 180^{\circ} - \angle PAC - \angle PBC</math>. Now we will show that <math>\angle ZPY = 180^{\circ} - \angle PAC - \angle PBC</math>. Note that, by cyclic quadrilaterals, <math>\angle YZP = \angle PAC</math> and <math>\angle ZYP = \angle PBC</math>. Hence, <math>\angle ZPY = 180^{\circ} - \angle PAC - \angle PBC</math> (since <math>\angle ZPY + \angle YZP + \angle ZYP = 180^{\circ}</math>), proving the aforementioned claim. Then, since <math>\angle ACB = 60^{\circ}</math> and <math>\angle AXB = \theta = 90^{\circ}</math>, <math>\angle ZPY = 150^{\circ}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Now we calculate <math>PY</math> and <math>PZ</math>, which are simply the diameters of circumcircles <math>\omega_{BC}</math> and <math>\omega_{AC}</math>, respectively. By the extended law of sines, <math>PY = \frac{BC}{\sin{BPC}} = \frac{\sqrt{37}}{2\sqrt{3}}</math> and <math>PZ = \frac{CA}{\sin{CPA}} = \frac{\sqrt{37}}{5}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | We can now solve for <math>ZY</math> with the law of cosines: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <cmath>(ZY)^2 = \frac{37}{25} + \frac{37}{12} - \left(\frac{37}{5\sqrt{3}}\right)\left(-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <cmath>(ZY)^2 = \frac{37}{25} + \frac{37}{12} + \frac{37}{10}</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <cmath>(ZY)^2 = \frac{37 \cdot 67}{300}</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <cmath>ZY = \sqrt{37} \cdot \frac{\sqrt{67}}{10\sqrt{3}}</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Now we will apply this discovery towards our original triangle <math>S</math>. Since the ratio between <math>ZY</math> and the hypotenuse of <math>S</math> is <math>\frac{\sqrt{67}}{10\sqrt{3}}</math>, the side length of the equilateral triangle inscribed within <math>S</math> must be <math>\frac{10\sqrt{3}}{\sqrt{67}}</math> (as <math>S</math> is simply as scaled version of <math>XYZ</math>, and thus their corresponding inscribed equilateral triangles must be scaled by the same factor). Then the area of the equilateral triangle inscribed within <math>S</math> is <math>\frac{75\sqrt{3}}{67}</math>, implying that the answer is <math>\boxed{145}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''-Solution by TheBoomBox77''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 10== | ||

| + | Let the right triangle's lower-left point be at <math>O(0,0)</math>. Notice the 2 other points will determine a unique equilateral triangle. Let 2 points be on the <math>x</math>-axis (<math>B</math>) and the <math>y</math>-axis (<math>A</math>) and label them <math>(b, 0)</math> and <math>(0, a)</math> respectively. The third point (<math>C</math>) will then be located on the hypotenuse. We proceed to find the third point's coordinates in terms of <math>a</math> and <math>b</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | 1. Find the slope of <math>AB</math> and take the negative reciprocal of it to find the slope of the line containing <math>C</math>. Notice the line contains the midpoint of <math>AB</math> so we can then have an equation of the line. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2. Let <math>AB=x.</math> For <math>ABC</math> to be an equilateral triangle, the altitude from <math>C</math> to <math>AB</math> must be <math>\frac{x\sqrt{3}}{2}.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | We then have two equations and two variables, so we can solve for <math>C</math>'s coordinates. | ||

| + | |||

| + | We can find <math>C(\frac{a+b\sqrt{3}}{2}), (\frac{b+a\sqrt{3}}{2}).</math> | ||

| + | Also, note that <math>C</math> must be on the hypotenuse of the triangle <math>\frac{x}{5}+\frac{y}{2\sqrt{3}}=1.</math> We can plug in <math>x</math> and <math>y</math> as the coordinates of <math>C</math>, which simplifies to | ||

| + | |||

| + | <cmath>11b+7\sqrt{3}a=20\sqrt{3}.</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | We aim to minimize the side length of the triangle, which is <math>\sqrt{a^2+b^2}.</math> Applying the Cauchy inequality gives us | ||

| + | |||

| + | <cmath>(a^2+b^2)(7\sqrt{3}^2+11^2)\geq (11b+7\sqrt3a)^2 = 1200</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | From which we obtain <math>\sqrt{a^2+b^2} \geq \sqrt{\frac{300}{67}}.</math> Thus, the area of the triangle = <math>\frac{75\sqrt{3}}{67}</math> which leads to the answer <math>75+3+67=\boxed{145}.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | -hi_im_bob | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 11== | ||

| + | [[File:AIME2017_P15.png|430px|right]] | ||

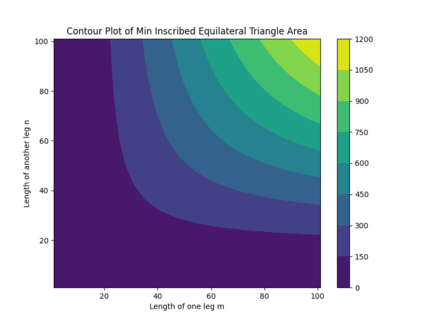

| + | The general solution to the minimal area is as following: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <cmath>A_{min}={{\sqrt{3}m^2n^2}\over{4(m^2+n^2+\sqrt{3}mn)}},</cmath> | ||

| + | |||

| + | where <math>m</math> and <math>n</math> are the two legs of the right triangle. In this particular case <math>m=5</math> and <math>n=2\sqrt{3}</math>. When we plug in these two values, we recover the correct answer of <math>\frac{75\sqrt3}{67}</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The contour of the minimal area <math>A_{min}</math> is plotted as a function of leg lengths <math>m</math> and <math>n</math>, as shown on the right hand side. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Note=== | ||

| + | The proof of the formula can be done in a similar fashion as Solution 4, where instead of using specific values, we define variables, <math>m</math> and <math>n</math> in this case, as per the formula. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Solution 12 (Geometry)== | ||

| + | [[File:2017 AIME I 15b.png|400px|right]] | ||

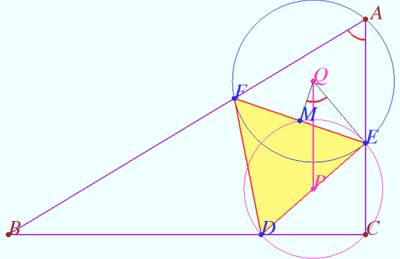

| + | Let <math>ED = DF = x, AC = 5, \angle BAC = \alpha.</math> | ||

| + | Then <math>\cot \alpha = \frac {5}{2\sqrt{3}}.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>P -</math> midpoint <math>DE, M - </math> midpoint <math>FE, Q -</math> circumcenter <math>\triangle AE.</math> | ||

| + | <cmath>\angle EQM = \alpha, \angle MQE = 90^\circ - \alpha, </cmath> | ||

| + | <cmath>\angle PEQ = \angle MQE + 60^\circ = 150^\circ - \alpha.</cmath> | ||

| + | <cmath>PE = \frac {x}{2}, QE = \frac {x}{2 \sin \alpha} \implies</cmath> | ||

| + | <cmath>PQ^2 = PE^2 + QE^2 - 2 PE \cdot QE \cdot \cos(150^\circ - \alpha),</cmath> | ||

| + | <cmath>PQ^2 = \frac{x^2}{4} (\cot ^2 \alpha + \sqrt {3} \cot \alpha + 1) .</cmath> | ||

| + | Points <math>P</math> and <math>Q</math> lies on bisectors of <math>CE</math> and <math>AE,</math> so <math>PQ \ge \frac {AC}{2}.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The smallest area <math>[DEF]</math> is | ||

| + | <cmath>\frac {\sqrt {3}}{4} \cdot x_{min}^2 = \frac {\sqrt {3} AC^2}{4 (\cot ^2 \alpha + \sqrt {3} \cot \alpha + 1)} = \frac{75 \sqrt{3}}{67}.</cmath> | ||

| + | '''vladimir.shelomovskii@gmail.com, vvsss''' | ||

| + | ==Solution 13 (Kinematics+Geometry)== | ||

| + | [[File:2017 AIME I 15c.png|430px|right]] | ||

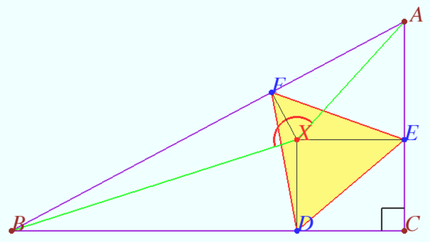

| + | Let <math>ED = DF = x, AC = 5, \angle BAC = \alpha.</math> | ||

| + | Then <math>\cot \alpha = \frac {5}{2\sqrt{3}}.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Let the required triangle with minimal sides <math>DEF</math> be constructed. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Let us vary its position in an acceptable way, that is, we will perform a movement in which the vertices of the <math>\triangle DEF</math> remain on the sides of the <math>\triangle ABC.</math> Any motion of a solid plane figure can be considered as rotation around some point, the center of rotation. The speed of movement of any point is perpendicular to the segment from the center of rotation to this point. With an acceptable variation, the velocities of the vertices of the <math>\triangle DEF</math> are directed along the sides <math>\triangle ABC.</math> Consequently, there is a point <math>X</math> located at the intersection of perpendiculars to the sides of <math>\triangle ABC,</math> around which <math>\triangle DEF</math> rotates. The bases of the perpendiculars dropped from <math>X</math> to the sides of <math>\triangle ABC</math> form a regular <math>\triangle DEF.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Therefore <math>X</math> is the first isodynamic point of <math>\triangle ABC.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | It is known that <math>\angle AXB = \angle ACB + 60^\circ = 150^\circ.</math> | ||

| − | + | The points <math>A, F, X,</math> and <math>E</math> are concyclic, <math>AX</math> is the diameter, so <math>AX = \frac {x}{\sin \alpha}.</math> Similarly, <math>BX = \frac {x}{\cos \alpha}.</math> | |

| + | <cmath>AX^2 + BX^2 - 2 AX BX \cos 150^\circ = AB^2, AC = AB \cos \alpha \implies </cmath> | ||

| + | <cmath>AC^2 = x^2 \cdot (\cot ^2 \alpha + \sqrt {3} \cot \alpha + 1).</cmath> | ||

| + | The smallest area <math>[DEF]</math> is | ||

| + | <cmath>\frac {\sqrt {3}}{4} \cdot x_{min}^2 = \frac {\sqrt {3} AC^2}{4 (\cot ^2 \alpha + \sqrt {3} \cot \alpha + 1)} = \frac{75 \sqrt{3}}{67}.</cmath> | ||

| + | '''vladimir.shelomovskii@gmail.com, vvsss''' | ||

==See Also== | ==See Also== | ||

{{AIME box|year=2017|n=I|num-b=14|after=Last Problem}} | {{AIME box|year=2017|n=I|num-b=14|after=Last Problem}} | ||

{{MAA Notice}} | {{MAA Notice}} | ||

Latest revision as of 21:06, 10 October 2024

Contents

Problem 15

The area of the smallest equilateral triangle with one vertex on each of the sides of the right triangle with side lengths ![]() and

and ![]() as shown, is

as shown, is ![]() where

where ![]() and

and ![]() are positive integers,

are positive integers, ![]() and

and ![]() are relatively prime, and

are relatively prime, and ![]() is not divisible by the square of any prime. Find

is not divisible by the square of any prime. Find ![]()

![[asy] size(5cm); pair C=(0,0),B=(0,2*sqrt(3)),A=(5,0); real t = .385, s = 3.5*t-1; pair R = A*t+B*(1-t), P=B*s; pair Q = dir(-60) * (R-P) + P; fill(P--Q--R--cycle,gray); draw(A--B--C--A^^P--Q--R--P); dot(A--B--C--P--Q--R); [/asy]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/2/0/4/2040951aabf67ea7477c8aa658e56ccda3a56492.png)

Solution 1

Lemma: If ![]() satisfy

satisfy ![]() , then the minimal value of

, then the minimal value of ![]() is

is ![]() .

.

Proof: Recall that the distance between the point ![]() and the line

and the line ![]() is given by

is given by ![]() . In particular, the distance between the origin and any point

. In particular, the distance between the origin and any point ![]() on the line

on the line ![]() is at least

is at least ![]() .

.

---

Let the vertices of the right triangle be ![]() and let

and let ![]() be the two vertices of the equilateral triangle on the legs of the right triangle. Then, the third vertex of the equilateral triangle is

be the two vertices of the equilateral triangle on the legs of the right triangle. Then, the third vertex of the equilateral triangle is  . This point must lie on the hypotenuse

. This point must lie on the hypotenuse ![]() , i.e.

, i.e. ![]() must satisfy

must satisfy

![]() which can be simplified to

which can be simplified to

![]()

By the lemma, the minimal value of ![]() is

is

![\[\frac{1}{\sqrt{\left(\frac{7}{20}\right)^2 + \left(\frac{11\sqrt{3}}{60}\right)^2}} = \frac{10\sqrt{3}}{\sqrt{67}},\]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/9/4/d/94dba6f485bdf86325dcb8d0fd0562ff38adff02.png) so the minimal area of the equilateral triangle is

so the minimal area of the equilateral triangle is

![\[\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4} \cdot \left(\frac{10\sqrt{3}}{\sqrt{67}}\right)^2 = \frac{\sqrt{3}}{4} \cdot \frac{300}{67} = \frac{75\sqrt{3}}{67},\]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/f/a/2/fa2164930d825d52eda5643945d73784f51576ea.png) and hence the answer is

and hence the answer is ![]() .

.

Solution 2

Let ![]() ,

, ![]() lies on

lies on ![]() ,

, ![]() lies on

lies on ![]() and

and ![]() lies on

lies on ![]()

Set ![]() as the origin,

as the origin, ![]() ,

, ![]() can be expressed as

can be expressed as ![]() in argand plane, the distance of

in argand plane, the distance of ![]() is

is ![]()

We know that ![]() . We know that the slope of

. We know that the slope of ![]() is

is ![]() , we have that

, we have that  , after computation, we have

, after computation, we have ![]()

Now the rest is easy with C-S inequality, ![]() so the smallest area is

so the smallest area is ![]() , and the answer is

, and the answer is ![]()

~bluesoul

Solution 3

Let ![]() be the right triangle with sides

be the right triangle with sides ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() and right angle at

and right angle at ![]() .

.

Let an equilateral triangle touch ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() at

at ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() respectively, having side lengths of

respectively, having side lengths of ![]() .

.

Now, call ![]() as

as ![]() and

and ![]() as

as ![]() . Thus,

. Thus, ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

By Law of Sines on triangles ![]() and

and ![]() ,

,

![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Summing,

![]() .

.

Now substituting ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() and solving,

and solving,

![]() .

.

We seek to minimize ![]() .

.

This is equivalent to minimizing ![]() .

.

Using the lemma from solution 1, we conclude that ![]()

Thus, ![]() and our final answer is

and our final answer is ![]()

- Awsomness2000

Solution 4 (Trigonometry)

Let ![]()

Then ![]()

![]()

By Law of Sines on triangle ![]() we get

we get

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![\[\frac{AC}{x} \le \sqrt {\left(\cot \alpha + \frac {\sqrt3}{2}\right)^2 + \left(\frac {1}{2}\right)^2} = \sqrt {\cot^2 \alpha + \sqrt {3} \cot \alpha + 1}\]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/c/3/1/c31638468dabc20b97006d3a1ab89205bb61ac36.png) The smallest area

The smallest area ![]() is

is

![]() vladimir.shelomovskii@gmail.com, vvsss

vladimir.shelomovskii@gmail.com, vvsss

Note

![]() follows from Cauchy-Schwarz.

follows from Cauchy-Schwarz.

![]() ~mathboy282

~mathboy282

Solution 5 (Complex numbers)

We will use complex numbers. Set the vertex at the right angle to be the origin, and set the axes so the other two vertices are ![]() and

and ![]() , respectively. Now let the vertex of the equilateral triangle on the real axis be

, respectively. Now let the vertex of the equilateral triangle on the real axis be ![]() and let the vertex of the equilateral triangle on the imaginary axis be

and let the vertex of the equilateral triangle on the imaginary axis be ![]() . Then, the third vertex of the equilateral triangle is given by:

. Then, the third vertex of the equilateral triangle is given by:

![]() .

.

For this to be on the hypotenuse of the right triangle, we also have the following:

![\[\frac{\frac{a\sqrt{3}}{2}+\frac{1}{2}}{\frac{a}{2}+\frac{b\sqrt{3}}{2}-5}=-\frac{2\sqrt{3}}{5}\iff 7\sqrt{3}a+11b=20\sqrt{3}\]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/b/9/8/b989f24f27bf88a37a1fa4d8b41fb770fa9f4a47.png)

Note that the area of the equilateral triangle is given by ![]() , so we seek to minimize

, so we seek to minimize ![]() . This can be done by using the Cauchy Schwarz Inequality on the relation we derived above:

. This can be done by using the Cauchy Schwarz Inequality on the relation we derived above:

![]()

Thus, the minimum we seek is simply ![]() , so the desired answer is

, so the desired answer is ![]() .

.

Solution 6

In the complex plane, let the vertices of the triangle be ![]()

![]() and

and ![]() Let

Let ![]() be one of the vertices, where

be one of the vertices, where ![]() is real. A point on the line passing through

is real. A point on the line passing through ![]() and

and ![]() can be expressed in the form

can be expressed in the form

![]() We want the third vertex

We want the third vertex ![]() to lie on the line through

to lie on the line through ![]() and

and ![]() which is the imaginary axis, so its real part is 0.

Since the small triangle is equilateral,

which is the imaginary axis, so its real part is 0.

Since the small triangle is equilateral, ![]() or

or

![]() Then the real part of

Then the real part of ![]() is

is

![]() Solving for

Solving for ![]() in terms of

in terms of ![]() we find

we find

![]() Then

Then

![]() so

so

![]() so

so

This quadratic is minimized when

This quadratic is minimized when ![]() and the minimum is

and the minimum is ![]() so the smallest area of the equilateral triangle is

so the smallest area of the equilateral triangle is

![\[\frac{\sqrt{3}}{4} \cdot \frac{300}{67} = \boxed{\frac{75 \sqrt{3}}{67}}.\]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/d/8/a/d8af728ad51851aba3c843fe958eff1c62019708.png)

Solution 7

We can use complex numbers. Set the origin at the right angle. Let the point on the real axis be ![]() and the point on the imaginary axis be

and the point on the imaginary axis be ![]() . Then, we see that

. Then, we see that  Now we switch back to Cartesian coordinates. The equation of the hypotenuse is

Now we switch back to Cartesian coordinates. The equation of the hypotenuse is ![]() This means that the point

This means that the point  is on the line. Plugging the numbers in, we have

is on the line. Plugging the numbers in, we have ![]() Now, we note that the side length of the equilateral triangle is

Now, we note that the side length of the equilateral triangle is ![]() so it suffices to minimize that. By Cauchy-Schwarz, we have

so it suffices to minimize that. By Cauchy-Schwarz, we have ![]() Thus, the area of the smallest triangle is

Thus, the area of the smallest triangle is ![]() so our desired answer is

so our desired answer is ![]() .

.

(Solution by Pleaseletmetwin, but not added to the Wiki by Pleaseletmetwin)

Solution 8

Employ the same complex bash as in Solution 5, but instead note that minimizing ![]() is the same as minimizing the distance from

0,0 to x,y, since they are the same quantity. We use point to plane instead, which gives you the required distance.

is the same as minimizing the distance from

0,0 to x,y, since they are the same quantity. We use point to plane instead, which gives you the required distance.

Solution 9 (Non Analytic)

Let ![]() be the triangle with side lengths

be the triangle with side lengths ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

We will think about this problem backwards, by constructing a triangle as large as possible (We will call it ![]() , for convenience) which is similar to

, for convenience) which is similar to ![]() with vertices outside of a unit equilateral triangle

with vertices outside of a unit equilateral triangle ![]() , such that each vertex of the equilateral triangle lies on a side of

, such that each vertex of the equilateral triangle lies on a side of ![]() . After we find the side lengths of

. After we find the side lengths of ![]() , we will use ratios to trace back towards the original problem.

, we will use ratios to trace back towards the original problem.

First of all, let ![]() ,

,  , and

, and ![]() (These three angles are simply the angles of triangle

(These three angles are simply the angles of triangle ![]() ; out of these three angles,

; out of these three angles, ![]() is the smallest angle, and

is the smallest angle, and ![]() is the largest angle). Then let us consider a point

is the largest angle). Then let us consider a point ![]() inside

inside ![]() such that

such that ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . Construct the circumcircles

. Construct the circumcircles ![]() and

and ![]() of triangles

of triangles ![]() and

and ![]() respectively.

respectively.

From here, we will prove the lemma that if we choose points ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() on circumcircles

on circumcircles ![]() and

and ![]() respectively such that

respectively such that ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are collinear and

are collinear and ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are collinear, then

are collinear, then ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() must be collinear. First of all, if we let

must be collinear. First of all, if we let ![]() , then

, then ![]() (by the properties of cyclic quadrilaterals),

(by the properties of cyclic quadrilaterals), ![]() (by adjacent angles),

(by adjacent angles), ![]() (by cyclic quadrilaterals),

(by cyclic quadrilaterals), ![]() (adjacent angles), and

(adjacent angles), and ![]() (cyclic quadrilaterals). Since

(cyclic quadrilaterals). Since ![]() and

and ![]() are supplementary,

are supplementary, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are collinear as desired. Hence,

are collinear as desired. Hence, ![]() has an inscribed equilateral triangle

has an inscribed equilateral triangle ![]() .

.

In addition, now we know that all triangles ![]() (as described above) must be similar to triangle

(as described above) must be similar to triangle ![]() , as

, as ![]() and

and ![]() , so we have developed

, so we have developed ![]() similarity between the two triangles. Thus,

similarity between the two triangles. Thus, ![]() is the triangle similar to

is the triangle similar to ![]() which we were desiring. Our goal now is to maximize the length of

which we were desiring. Our goal now is to maximize the length of ![]() , in order to maximize the area of

, in order to maximize the area of ![]() , to achieve our original goal.

, to achieve our original goal.

Note that, all triangles ![]() are similar to each other if

are similar to each other if ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are collinear. This is because

are collinear. This is because ![]() is constant, and

is constant, and ![]() is also a constant value. Then we have

is also a constant value. Then we have ![]() similarity between this set of triangles. To maximize

similarity between this set of triangles. To maximize ![]() , we can instead maximize

, we can instead maximize ![]() , which is simply the diameter of

, which is simply the diameter of ![]() . From there, we can determine that

. From there, we can determine that ![]() , and with similar logic,

, and with similar logic, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are perpendicular to

are perpendicular to ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() respectively We have found our desired largest possible triangle

respectively We have found our desired largest possible triangle ![]() .

.

All we have to do now is to calculate ![]() , and use ratios from similar triangles to determine the side length of the equilateral triangle inscribed within

, and use ratios from similar triangles to determine the side length of the equilateral triangle inscribed within ![]() . First of all, we will prove that

. First of all, we will prove that ![]() . By the properties of cyclic quadrilaterals,

. By the properties of cyclic quadrilaterals, ![]() , which means that

, which means that ![]() . Now we will show that

. Now we will show that ![]() . Note that, by cyclic quadrilaterals,

. Note that, by cyclic quadrilaterals, ![]() and

and ![]() . Hence,

. Hence, ![]() (since

(since ![]() ), proving the aforementioned claim. Then, since

), proving the aforementioned claim. Then, since ![]() and

and ![]() ,

, ![]() .

.

Now we calculate ![]() and

and ![]() , which are simply the diameters of circumcircles

, which are simply the diameters of circumcircles ![]() and

and ![]() , respectively. By the extended law of sines,

, respectively. By the extended law of sines, ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

We can now solve for ![]() with the law of cosines:

with the law of cosines:

![\[(ZY)^2 = \frac{37}{25} + \frac{37}{12} - \left(\frac{37}{5\sqrt{3}}\right)\left(-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)\]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/3/9/2/3928918d3a3fde7254bf342cbfbea4bfae557f3c.png)

![]()

![]()

![]()

Now we will apply this discovery towards our original triangle ![]() . Since the ratio between

. Since the ratio between ![]() and the hypotenuse of

and the hypotenuse of ![]() is

is ![]() , the side length of the equilateral triangle inscribed within

, the side length of the equilateral triangle inscribed within ![]() must be

must be ![]() (as

(as ![]() is simply as scaled version of

is simply as scaled version of ![]() , and thus their corresponding inscribed equilateral triangles must be scaled by the same factor). Then the area of the equilateral triangle inscribed within

, and thus their corresponding inscribed equilateral triangles must be scaled by the same factor). Then the area of the equilateral triangle inscribed within ![]() is

is ![]() , implying that the answer is

, implying that the answer is ![]() .

.

-Solution by TheBoomBox77

Solution 10

Let the right triangle's lower-left point be at ![]() . Notice the 2 other points will determine a unique equilateral triangle. Let 2 points be on the

. Notice the 2 other points will determine a unique equilateral triangle. Let 2 points be on the ![]() -axis (

-axis (![]() ) and the

) and the ![]() -axis (

-axis (![]() ) and label them

) and label them ![]() and

and ![]() respectively. The third point (

respectively. The third point (![]() ) will then be located on the hypotenuse. We proceed to find the third point's coordinates in terms of

) will then be located on the hypotenuse. We proceed to find the third point's coordinates in terms of ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

1. Find the slope of ![]() and take the negative reciprocal of it to find the slope of the line containing

and take the negative reciprocal of it to find the slope of the line containing ![]() . Notice the line contains the midpoint of

. Notice the line contains the midpoint of ![]() so we can then have an equation of the line.

so we can then have an equation of the line.

2. Let ![]() For

For ![]() to be an equilateral triangle, the altitude from

to be an equilateral triangle, the altitude from ![]() to

to ![]() must be

must be ![]()

We then have two equations and two variables, so we can solve for ![]() 's coordinates.

's coordinates.

We can find ![]() Also, note that

Also, note that ![]() must be on the hypotenuse of the triangle

must be on the hypotenuse of the triangle ![]() We can plug in

We can plug in ![]() and

and ![]() as the coordinates of

as the coordinates of ![]() , which simplifies to

, which simplifies to

![]()

We aim to minimize the side length of the triangle, which is ![]() Applying the Cauchy inequality gives us

Applying the Cauchy inequality gives us

![]()

From which we obtain ![]() Thus, the area of the triangle =

Thus, the area of the triangle = ![]() which leads to the answer

which leads to the answer ![]()

-hi_im_bob

Solution 11

The general solution to the minimal area is as following:

![]()

where ![]() and

and ![]() are the two legs of the right triangle. In this particular case

are the two legs of the right triangle. In this particular case ![]() and

and ![]() . When we plug in these two values, we recover the correct answer of

. When we plug in these two values, we recover the correct answer of ![]() .

.

The contour of the minimal area ![]() is plotted as a function of leg lengths

is plotted as a function of leg lengths ![]() and

and ![]() , as shown on the right hand side.

, as shown on the right hand side.

Note

The proof of the formula can be done in a similar fashion as Solution 4, where instead of using specific values, we define variables, ![]() and

and ![]() in this case, as per the formula.

in this case, as per the formula.

Solution 12 (Geometry)

Let ![]() Then

Then ![]()

![]() midpoint

midpoint ![]() midpoint

midpoint ![]() circumcenter

circumcenter ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Points

Points ![]() and

and ![]() lies on bisectors of

lies on bisectors of ![]() and

and ![]() so

so ![]()

The smallest area ![]() is

is

![]() vladimir.shelomovskii@gmail.com, vvsss

vladimir.shelomovskii@gmail.com, vvsss

Solution 13 (Kinematics+Geometry)

Let ![]() Then

Then ![]()

Let the required triangle with minimal sides ![]() be constructed.

be constructed.

Let us vary its position in an acceptable way, that is, we will perform a movement in which the vertices of the ![]() remain on the sides of the

remain on the sides of the ![]() Any motion of a solid plane figure can be considered as rotation around some point, the center of rotation. The speed of movement of any point is perpendicular to the segment from the center of rotation to this point. With an acceptable variation, the velocities of the vertices of the

Any motion of a solid plane figure can be considered as rotation around some point, the center of rotation. The speed of movement of any point is perpendicular to the segment from the center of rotation to this point. With an acceptable variation, the velocities of the vertices of the ![]() are directed along the sides

are directed along the sides ![]() Consequently, there is a point

Consequently, there is a point ![]() located at the intersection of perpendiculars to the sides of

located at the intersection of perpendiculars to the sides of ![]() around which

around which ![]() rotates. The bases of the perpendiculars dropped from

rotates. The bases of the perpendiculars dropped from ![]() to the sides of

to the sides of ![]() form a regular

form a regular ![]()

Therefore ![]() is the first isodynamic point of

is the first isodynamic point of ![]()

It is known that ![]()

The points ![]() and

and ![]() are concyclic,

are concyclic, ![]() is the diameter, so

is the diameter, so ![]() Similarly,

Similarly, ![]()

![]()

![]() The smallest area

The smallest area ![]() is

is

![]() vladimir.shelomovskii@gmail.com, vvsss

vladimir.shelomovskii@gmail.com, vvsss

See Also

| 2017 AIME I (Problems • Answer Key • Resources) | ||

| Preceded by Problem 14 |

Followed by Last Problem | |

| 1 • 2 • 3 • 4 • 5 • 6 • 7 • 8 • 9 • 10 • 11 • 12 • 13 • 14 • 15 | ||

| All AIME Problems and Solutions | ||

The problems on this page are copyrighted by the Mathematical Association of America's American Mathematics Competitions.