Difference between revisions of "1984 AHSME Problems"

m (→Problem 21) |

Made in 2016 (talk | contribs) |

||

| (45 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{AHSME Problems | ||

| + | |year = 1984 | ||

| + | }} | ||

==Problem 1== | ==Problem 1== | ||

<math> \frac{1000^2}{252^2-248^2} </math> equals | <math> \frac{1000^2}{252^2-248^2} </math> equals | ||

| − | <math> \mathrm{(A) \ } | + | <math> \mathrm{(A) \ }62500 \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }1000 \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } 500\qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }250 \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } \frac{1}{2} </math> |

[[1984 AHSME Problems/Problem 1|Solution]] | [[1984 AHSME Problems/Problem 1|Solution]] | ||

| Line 10: | Line 13: | ||

If <math> x, y </math>, and <math> y-\frac{1}{x} </math> are not <math> 0 </math>, then | If <math> x, y </math>, and <math> y-\frac{1}{x} </math> are not <math> 0 </math>, then | ||

| − | < | + | <cmath> \frac{x-\frac{1}{y}}{y-\frac{1}{x}} </cmath> |

| + | equals | ||

<math> \mathrm{(A) \ }1 \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }\frac{x}{y} \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } \frac{y}{x}\qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }\frac{x}{y}-\frac{y}{x} \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } xy-\frac{1}{xy} </math> | <math> \mathrm{(A) \ }1 \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }\frac{x}{y} \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } \frac{y}{x}\qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }\frac{x}{y}-\frac{y}{x} \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } xy-\frac{1}{xy} </math> | ||

| Line 24: | Line 28: | ||

==Problem 4== | ==Problem 4== | ||

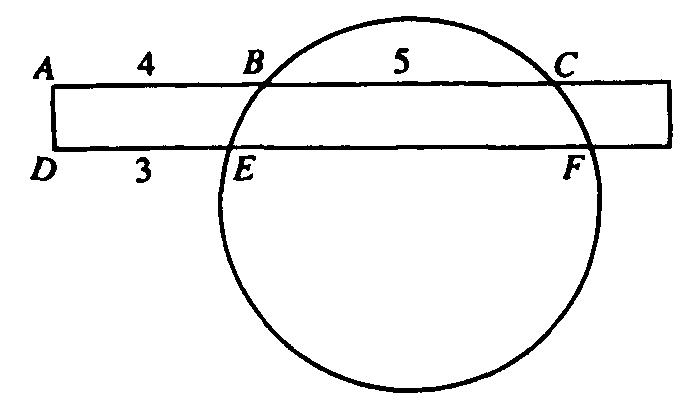

| − | + | A rectangle intersects a circle as shown: <math>AB = 4</math>, <math>BC = 5</math> and <math>DE = 3</math>. Then <math>EF</math> equals | |

| + | [[File:AHSME-1984-Q4.jpg]] | ||

| − | {{ | + | <math> \mathrm{(A) \ }6 \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }7 \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ }\frac{20}{3} \qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }8 \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ }9 </math> |

| − | |||

[[1984 AHSME Problems/Problem 4|Solution]] | [[1984 AHSME Problems/Problem 4|Solution]] | ||

| Line 39: | Line 43: | ||

==Problem 6== | ==Problem 6== | ||

| − | In a certain school, there are | + | In a certain school, there are three times as many boys as girls and nine times as many girls as teachers. Using the letters <math>b, g, t</math> to represent the number of boys, girls and teachers, respectively, then the total number of boys, girls and teachers can be represented by the [[expression]] |

| − | <math> \mathrm{(A) \ }31b \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }\frac{ | + | <math> \mathrm{(A) \ }31b \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }\frac{37}{27}b \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } 13g \qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }\frac{37}{27}g \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } \frac{37}{27}t </math> |

[[1984 AHSME Problems/Problem 6|Solution]] | [[1984 AHSME Problems/Problem 6|Solution]] | ||

==Problem 7== | ==Problem 7== | ||

| − | When Dave walks to school, he averages <math> 90 </math> steps per minute, | + | When Dave walks to school, he averages <math> 90 </math> steps per minute, each of his steps <math> 75 </math> cm long. It takes him <math> 16 </math> minutes to get to school. His brother, Jack, going to the same school by the same route, averages <math> 100 </math> steps per minute, but his steps are only <math> 60 </math> cm long. How long does it take Jack to get to school? |

| − | <math> \mathrm{(A) \ }14 \frac{2}{9} \text{minutes} \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }15 \text{minutes}\qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } 18 \text{minutes}\qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }20 \text{minutes} \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } 22 \frac{2}{9} \text{minutes} </math> | + | <math> \mathrm{(A) \ }14 \frac{2}{9} \text{ minutes} \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }15 \text{ minutes}\qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } 18 \text{ minutes}\qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }20 \text{ minutes} \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } 22 \frac{2}{9} \text{ minutes} </math> |

[[1984 AHSME Problems/Problem 7|Solution]] | [[1984 AHSME Problems/Problem 7|Solution]] | ||

==Problem 8== | ==Problem 8== | ||

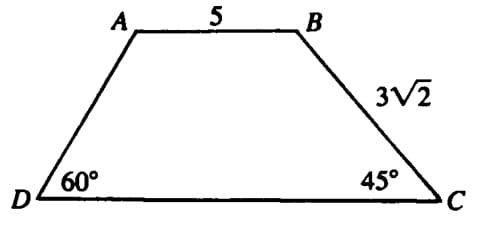

| − | Figure <math> ABCD </math> is a [[trapezoid]] with <math> AB||DC </math>, <math> AB=5 </math>, <math> BC=3\sqrt{2} </math>, <math> \angle BCD=45^\circ </math> | + | Figure <math> ABCD </math> is a [[trapezoid]] with <math> AB||DC </math>, <math> AB=5 </math>, <math> BC=3\sqrt{2} </math>, <math> \angle BCD=45^\circ </math> and <math> \angle CDA=60^\circ </math>. The length of <math> DC </math> is |

| + | |||

| + | [[File:AHSME-1984-Q8.jpg]] | ||

<math> \mathrm{(A) \ }7+\frac{2}{3}\sqrt{3} \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }8 \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } 9 \frac{1}{2} \qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }8+\sqrt{3} \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } 8+3\sqrt{3} </math> | <math> \mathrm{(A) \ }7+\frac{2}{3}\sqrt{3} \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }8 \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } 9 \frac{1}{2} \qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }8+\sqrt{3} \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } 8+3\sqrt{3} </math> | ||

| Line 67: | Line 73: | ||

==Problem 10== | ==Problem 10== | ||

| − | Four [[complex numbers]] lie at the [[vertices]] of a [[square]] in the [[complex plane]]. Three of the numbers are <math> 1+2i, -2+i </math> | + | Four [[complex numbers]] lie at the [[vertices]] of a [[square]] in the [[complex plane]]. Three of the numbers are <math> 1+2i, {-2}+i </math> and <math> {-1}-2i </math>. The fourth number is |

| − | <math> \mathrm{(A) \ }2+i \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }2-i \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } 1-2i \qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }-1+2i \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } -2-i </math> | + | <math> \mathrm{(A) \ }2+i \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }2-i \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } 1-2i \qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }{-1}+2i \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } {-2}-i </math> |

[[1984 AHSME Problems/Problem 10|Solution]] | [[1984 AHSME Problems/Problem 10|Solution]] | ||

==Problem 11== | ==Problem 11== | ||

| − | A calculator has a key that replaces the displayed entry with its [[Perfect square|square]], and another key which replaces the displayed entry with its [[reciprocal]]. Let <math> y </math> be the final result when one starts with | + | A calculator has a key that replaces the displayed entry with its [[Perfect square|square]], and another key which replaces the displayed entry with its [[reciprocal]]. Let <math> y </math> be the final result when one starts with an entry <math> x\not=0 |

</math> and alternately squares and reciprocates <math> n </math> times each. Assuming the calculator is completely accurate (e.g. no roundoff or overflow), then <math> y </math> equals | </math> and alternately squares and reciprocates <math> n </math> times each. Assuming the calculator is completely accurate (e.g. no roundoff or overflow), then <math> y </math> equals | ||

| Line 84: | Line 90: | ||

If the [[sequence]] <math> \{a_n\} </math> is defined by | If the [[sequence]] <math> \{a_n\} </math> is defined by | ||

| − | < | + | <cmath>a_1=2,</cmath> |

| − | + | <cmath>a_{n+1}=a_n+2n \qquad (n \geq 1),</cmath> | |

| − | < | ||

| − | + | then <math> a_{100} </math> equals | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

<math> \mathrm{(A) \ }9900 \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }9902 \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } 9904 \qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }10100 \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } 10102 </math> | <math> \mathrm{(A) \ }9900 \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }9902 \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } 9904 \qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }10100 \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } 10102 </math> | ||

| Line 99: | Line 102: | ||

<math> \frac{2\sqrt{6}}{\sqrt{2}+\sqrt{3}+\sqrt{5}} </math> equals | <math> \frac{2\sqrt{6}}{\sqrt{2}+\sqrt{3}+\sqrt{5}} </math> equals | ||

| − | <math> \mathrm{(A) \ }\sqrt{2}+\sqrt{3}-\sqrt{5} \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }4-\sqrt{2}-\sqrt{3} \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } \sqrt{2}+\sqrt{3}+\sqrt{6}-5 \qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }\frac{1}{2}(\sqrt{2}+\sqrt{5}-\sqrt{3}) \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } \frac{1}{3}(\sqrt{3}+\sqrt{5}-\sqrt{2}) </math> | + | <math> \mathrm{(A) \ }\sqrt{2}+\sqrt{3}-\sqrt{5} \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }4-\sqrt{2}-\sqrt{3} \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } \sqrt{2}+\sqrt{3}+\sqrt{6}-5 \qquad </math> |

| + | |||

| + | <math> \mathrm{(D) \ }\frac{1}{2}(\sqrt{2}+\sqrt{5}-\sqrt{3}) \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } \frac{1}{3}(\sqrt{3}+\sqrt{5}-\sqrt{2}) </math> | ||

[[1984 AHSME Problems/Problem 13|Solution]] | [[1984 AHSME Problems/Problem 13|Solution]] | ||

| Line 125: | Line 130: | ||

==Problem 17== | ==Problem 17== | ||

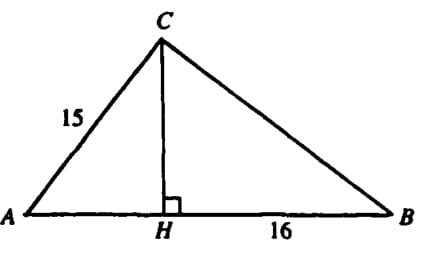

| − | A [[right triangle]] <math> ABC </math> with [[hypotenuse]] <math> AB </math> has side <math> AC=15 </math>. [[Altitude]] <math> CH </math> divides <math> AB </math> into segments <math> AH </math> and <math> HB </math>, with <math> HB=16 </math>. The [[area]] of <math> \triangle ABC </math> is: | + | A [[right triangle]] <math> ABC </math> with [[hypotenuse]] <math> AB </math> has side <math> AC=15 </math>. [[Altitude]] <math> CH </math> divides <math> AB </math> into segments <math> AH </math> and <math> HB </math>, with <math> HB=16 </math>. The [[area]] of <math> \triangle ABC </math> is |

| + | |||

| + | [[File:AHSME-1984-Q17.jpg]] | ||

<math> \mathrm{(A) \ }120 \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }144 \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } 150 \qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }216 \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } 144\sqrt{5} </math> | <math> \mathrm{(A) \ }120 \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }144 \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } 150 \qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }216 \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } 144\sqrt{5} </math> | ||

| Line 132: | Line 139: | ||

==Problem 18== | ==Problem 18== | ||

| − | A point <math> (x, y) </math> is to be chosen in the [[coordinate plane]] so that it is equally distant from the [[x-axis]], the [[y-axis]], and the [[line]] <math> x+y=2 </math>. Then <math> x </math> is | + | A point <math> (x, y) </math> is to be chosen in the [[coordinate plane]] so that it is equally distant from the [[x-axis|<math>x</math>-axis]], the [[y-axis|<math>y</math>-axis]], and the [[line]] <math> x+y=2 </math>. Then <math> x </math> is |

| − | <math> \mathrm{(A) \ }\sqrt{2}-1 \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }\frac{1}{2} \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } 2-\sqrt{2} \qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }1 \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } \text{ | + | <math> \mathrm{(A) \ }\sqrt{2}-1 \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }\frac{1}{2} \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } 2-\sqrt{2} \qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }1 \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } \text{not uniquely determined} </math> |

[[1984 AHSME Problems/Problem 18|Solution]] | [[1984 AHSME Problems/Problem 18|Solution]] | ||

==Problem 19== | ==Problem 19== | ||

| − | A box contains <math> 11 </math> balls, numbered <math> 1, 2, 3, | + | A box contains <math> 11 </math> balls, numbered <math> 1, 2, 3,\ldots,11 </math>. If <math> 6 </math> balls are drawn simultaneously at random, what is the [[probability]] that the sum of the numbers on the balls drawn is odd? |

<math> \mathrm{(A) \ }\frac{100}{231} \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }\frac{115}{231} \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } \frac{1}{2} \qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }\frac{118}{231} \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } \frac{6}{11} </math> | <math> \mathrm{(A) \ }\frac{100}{231} \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }\frac{115}{231} \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } \frac{1}{2} \qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }\frac{118}{231} \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } \frac{6}{11} </math> | ||

| Line 146: | Line 153: | ||

==Problem 20== | ==Problem 20== | ||

| − | The number of the distinct solutions | + | The number of the distinct solutions of the [[equation]] <math> |{x-|2x+1|}|=3 </math> is |

| − | |||

| − | <math> |x-|2x+1||=3 </math> is | ||

<math> \mathrm{(A) \ }0 \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }1 \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } 2 \qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }3 \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } 4 </math> | <math> \mathrm{(A) \ }0 \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }1 \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } 2 \qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }3 \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } 4 </math> | ||

| Line 155: | Line 160: | ||

==Problem 21== | ==Problem 21== | ||

| − | The number of triples <math> (a, b, c) </math> of [[Natural numbers|positive integers]] which satisfy the simultaneous equations | + | The number of triples <math> (a, b, c) </math> of [[Natural numbers|positive integers]] which satisfy the simultaneous [[Equation|equations]] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | < | + | <cmath> ab+bc=44,</cmath> |

| + | <cmath> ac+bc=23,</cmath> | ||

is | is | ||

| Line 168: | Line 172: | ||

==Problem 22== | ==Problem 22== | ||

| − | Let <math> a </math> and <math> c </math> be fixed positive numbers. For each real number <math> t </math> let <math> (x_t, y_t) </math> be the vertex of the parabola <math> y=ax^2+bx+c </math>. If the set of the vertices <math> (x_t, y_t) </math> for all real | + | Let <math> a </math> and <math> c </math> be fixed [[Natural numbers|positive numbers]]. For each [[real number]] <math> t </math> let <math> (x_t, y_t) </math> be the [[vertex]] of the [[parabola]] <math> y=ax^2+bx+c </math>. If the set of the vertices <math> (x_t, y_t) </math> for all real values of <math> t </math> is graphed on the [[Cartesian plane|plane]], the [[graph]] is |

| − | <math> \mathrm{(A) \ } \text{a straight line} \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ } \text{a parabola} \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } \text{part, but not all, of a parabola} \qquad \mathrm{(D) \ } \text{one branch of a hyperbola} \qquad | + | <math> \mathrm{(A) \ } \text{a straight line} \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ } \text{a parabola} \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } \text{part, but not all, of a parabola} \qquad \mathrm{(D) \ } \text{one branch of a hyperbola} \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } \text{none of these} </math> |

[[1984 AHSME Problems/Problem 22|Solution]] | [[1984 AHSME Problems/Problem 22|Solution]] | ||

| Line 182: | Line 186: | ||

==Problem 24== | ==Problem 24== | ||

| − | If <math> a </math> and <math> b </math> are positive real numbers and each of the equations <math> x^2+ax+2b=0 </math> and <math> x^2+2bx+a=0 </math> has real roots, then the smallest possible value of <math> a+b </math> is | + | If <math> a </math> and <math> b </math> are positive [[real numbers]] and each of the [[Equation|equations]] <math> x^2+ax+2b=0 </math> and <math> x^2+2bx+a=0 </math> has real [[Root (polynomial)|roots]], then the smallest possible value of <math> a+b </math> is |

<math> \mathrm{(A) \ }2 \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }3 \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } 4 \qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }5 \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } 6 </math> | <math> \mathrm{(A) \ }2 \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }3 \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } 4 \qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }5 \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } 6 </math> | ||

| Line 189: | Line 193: | ||

==Problem 25== | ==Problem 25== | ||

| − | The total area of all the faces of a rectangular solid is <math> 22\text{cm}^2 </math>, and the total length of all its edges is <math> 24\text{cm} </math>. Then the length in cm of any one of its interior diagonals is | + | The total [[area]] of all the [[faces]] of a [[Rectangular prism|rectangular solid]] is <math> 22 \ \text{cm}^2 </math>, and the total length of all its [[edges]] is <math> 24 \ \text{cm} </math>. Then the length in cm of any one of its [[Diagonal#Polyhedra|interior diagonals]] is |

| − | <math> \mathrm{(A) \ }\sqrt{11} \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }\sqrt{12} \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } \sqrt{13}\qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }\sqrt{14} \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } \text{ | + | <math> \mathrm{(A) \ }\sqrt{11} \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }\sqrt{12} \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } \sqrt{13}\qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }\sqrt{14} \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } \text{not uniquely determined} </math> |

[[1984 AHSME Problems/Problem 25|Solution]] | [[1984 AHSME Problems/Problem 25|Solution]] | ||

==Problem 26== | ==Problem 26== | ||

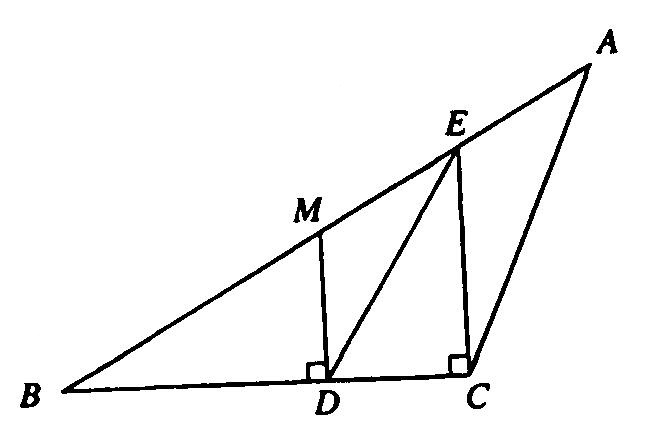

| − | In the obtuse triangle <math> ABC | + | In the [[obtuse triangle]] <math> ABC </math>, <math> AM=MB </math>, <math> MD\perp BC </math>, <math> EC\perp BC </math>. If the [[area]] of <math> \triangle ABC </math> is <math> 24 </math>, then the area of <math> \triangle BED </math> is |

| + | |||

| + | [[File:AHSME-1984-Q26.jpg]] | ||

| − | <math> \mathrm{(A) \ }9 \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }12 \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } 15 \qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }18 \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } \text{ | + | <math> \mathrm{(A) \ }9 \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }12 \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } 15 \qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }18 \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } \text{not uniquely determined} </math> |

[[1984 AHSME Problems/Problem 26|Solution]] | [[1984 AHSME Problems/Problem 26|Solution]] | ||

==Problem 27== | ==Problem 27== | ||

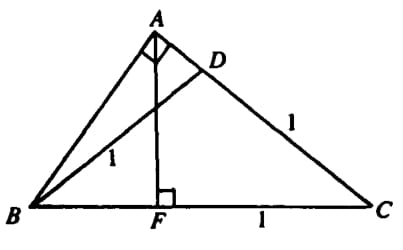

| − | In <math> \triangle ABC </math>, <math> D </math> is on <math> AC </math> and <math> F </math> is on <math> BC </math>. Also, <math> AB\ | + | In <math> \triangle ABC </math>, <math> D </math> is on <math> AC </math> and <math> F </math> is on <math> BC </math>. Also, <math> AB\perp AC </math>, <math> AF\perp BC </math>, and <math> BD=DC=FC=1 </math>. Find <math> AC </math>. |

| + | |||

| + | [[File:AHSME-1984-Q27.jpg]] | ||

<math> \mathrm{(A) \ }\sqrt{2} \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }\sqrt{3} \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } \sqrt[3]{2} \qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }\sqrt[3]{3} \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } \sqrt[4]{3} </math> | <math> \mathrm{(A) \ }\sqrt{2} \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }\sqrt{3} \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } \sqrt[3]{2} \qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }\sqrt[3]{3} \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } \sqrt[4]{3} </math> | ||

| Line 210: | Line 218: | ||

==Problem 28== | ==Problem 28== | ||

| − | The number of distinct pairs of integers <math> (x, y) </math> such that <math> 0<x<y </math> and <math> \sqrt{1984}=\sqrt{x}+\sqrt{y} </math> is | + | The number of distinct pairs of [[integers]] <math> (x, y) </math> such that <math> 0<x<y </math> and <math> \sqrt{1984}=\sqrt{x}+\sqrt{y} </math> is |

<math> \mathrm{(A) \ }0 \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }1 \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } 3 \qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }4 \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } 7 </math> | <math> \mathrm{(A) \ }0 \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }1 \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } 3 \qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }4 \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } 7 </math> | ||

| Line 217: | Line 225: | ||

==Problem 29== | ==Problem 29== | ||

| − | Find the largest value for <math> \frac{y}{x} </math> for pairs of real numbers <math> (x, y) </math> which satisfy <math> (x-3)^2+(y-3)^2=6 </math>. | + | Find the largest value for <math> \frac{y}{x} </math> for pairs of [[real numbers]] <math> (x, y) </math> which satisfy <math> (x-3)^2+(y-3)^2=6 </math>. |

<math> \mathrm{(A) \ }3+2\sqrt{2} \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }2+\sqrt{3} \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } 3\sqrt{3} \qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }6 \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } 6+2\sqrt{3} </math> | <math> \mathrm{(A) \ }3+2\sqrt{2} \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }2+\sqrt{3} \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } 3\sqrt{3} \qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }6 \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } 6+2\sqrt{3} </math> | ||

| Line 224: | Line 232: | ||

==Problem 30== | ==Problem 30== | ||

| − | For any complex number <math> w=a+bi </math>, <math> |w| </math> is defined to be the real number <math> \sqrt{a^2+b^2} </math>. If <math> w=\cos40^\circ+i\sin40^\circ </math>, then | + | For any [[complex number]] <math> w=a+bi </math>, <math> |w| </math> is defined to be the [[real number]] <math> \sqrt{a^2+b^2} </math>. If <math> w=\cos40^\circ+i\sin40^\circ </math>, then |

| + | <math> |w+2w^2+3w^3+...+9w^9|^{-1} </math> equals | ||

| − | <math> | + | <math> \mathrm{(A) \ }\frac{1}{9}\sin40^\circ \qquad \mathrm{(B) \ }\frac{2}{9}\sin20^\circ \qquad \mathrm{(C) \ } \frac{1}{9}\cos40^\circ \qquad \mathrm{(D) \ }\frac{1}{18}\cos20^\circ \qquad \mathrm{(E) \ } \text{none of these} </math> |

| − | + | [[1984 AHSME Problems/Problem 30|Solution]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | ==See | + | == See also == |

| − | *[[ | + | * [[AMC 12 Problems and Solutions]] |

| + | * [[Mathematics competition resources]] | ||

| − | + | {{AHSME box|year=1984|before=[[1983 AHSME]]|after=[[1985 AHSME]]}} | |

| − | + | {{MAA Notice}} | |

Latest revision as of 13:00, 19 February 2020

| 1984 AHSME (Answer Key) Printable versions: • AoPS Resources • PDF | ||

|

Instructions

| ||

| 1 • 2 • 3 • 4 • 5 • 6 • 7 • 8 • 9 • 10 • 11 • 12 • 13 • 14 • 15 • 16 • 17 • 18 • 19 • 20 • 21 • 22 • 23 • 24 • 25 • 26 • 27 • 28 • 29 • 30 | ||

Contents

- 1 Problem 1

- 2 Problem 2

- 3 Problem 3

- 4 Problem 4

- 5 Problem 5

- 6 Problem 6

- 7 Problem 7

- 8 Problem 8

- 9 Problem 9

- 10 Problem 10

- 11 Problem 11

- 12 Problem 12

- 13 Problem 13

- 14 Problem 14

- 15 Problem 15

- 16 Problem 16

- 17 Problem 17

- 18 Problem 18

- 19 Problem 19

- 20 Problem 20

- 21 Problem 21

- 22 Problem 22

- 23 Problem 23

- 24 Problem 24

- 25 Problem 25

- 26 Problem 26

- 27 Problem 27

- 28 Problem 28

- 29 Problem 29

- 30 Problem 30

- 31 See also

Problem 1

![]() equals

equals

![]()

Problem 2

If ![]() , and

, and ![]() are not

are not ![]() , then

, then

![]() equals

equals

![]()

Problem 3

Let ![]() be the smallest nonprime integer greater than

be the smallest nonprime integer greater than ![]() with no prime factor less than

with no prime factor less than ![]() . Then

. Then

![]()

Problem 4

A rectangle intersects a circle as shown: ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() equals

equals

![]()

Problem 5

The largest integer ![]() for which

for which ![]() is

is

![]()

Problem 6

In a certain school, there are three times as many boys as girls and nine times as many girls as teachers. Using the letters ![]() to represent the number of boys, girls and teachers, respectively, then the total number of boys, girls and teachers can be represented by the expression

to represent the number of boys, girls and teachers, respectively, then the total number of boys, girls and teachers can be represented by the expression

![]()

Problem 7

When Dave walks to school, he averages ![]() steps per minute, each of his steps

steps per minute, each of his steps ![]() cm long. It takes him

cm long. It takes him ![]() minutes to get to school. His brother, Jack, going to the same school by the same route, averages

minutes to get to school. His brother, Jack, going to the same school by the same route, averages ![]() steps per minute, but his steps are only

steps per minute, but his steps are only ![]() cm long. How long does it take Jack to get to school?

cm long. How long does it take Jack to get to school?

![]()

Problem 8

Figure ![]() is a trapezoid with

is a trapezoid with ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() . The length of

. The length of ![]() is

is

![]()

Problem 9

The number of digits in ![]() (when written in the usual base

(when written in the usual base ![]() form) is

form) is

![]()

Problem 10

Four complex numbers lie at the vertices of a square in the complex plane. Three of the numbers are ![]() and

and ![]() . The fourth number is

. The fourth number is

![]()

Problem 11

A calculator has a key that replaces the displayed entry with its square, and another key which replaces the displayed entry with its reciprocal. Let ![]() be the final result when one starts with an entry

be the final result when one starts with an entry ![]() and alternately squares and reciprocates

and alternately squares and reciprocates ![]() times each. Assuming the calculator is completely accurate (e.g. no roundoff or overflow), then

times each. Assuming the calculator is completely accurate (e.g. no roundoff or overflow), then ![]() equals

equals

![]()

Problem 12

If the sequence ![]() is defined by

is defined by

![]()

![]()

then ![]() equals

equals

![]()

Problem 13

![]() equals

equals

![]()

![]()

Problem 14

The product of all real roots of the equation ![]() is

is

![]()

Problem 15

If ![]() , then one value for

, then one value for ![]() is

is

![]()

Problem 16

The function ![]() satisfies

satisfies ![]() for all real numbers

for all real numbers ![]() . If the equation

. If the equation ![]() has exactly four distinct real roots, then the sum of these roots is

has exactly four distinct real roots, then the sum of these roots is

![]()

Problem 17

A right triangle ![]() with hypotenuse

with hypotenuse ![]() has side

has side ![]() . Altitude

. Altitude ![]() divides

divides ![]() into segments

into segments ![]() and

and ![]() , with

, with ![]() . The area of

. The area of ![]() is

is

![]()

Problem 18

A point ![]() is to be chosen in the coordinate plane so that it is equally distant from the

is to be chosen in the coordinate plane so that it is equally distant from the ![]() -axis, the

-axis, the ![]() -axis, and the line

-axis, and the line ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() is

is

![]()

Problem 19

A box contains ![]() balls, numbered

balls, numbered ![]() . If

. If ![]() balls are drawn simultaneously at random, what is the probability that the sum of the numbers on the balls drawn is odd?

balls are drawn simultaneously at random, what is the probability that the sum of the numbers on the balls drawn is odd?

![]()

Problem 20

The number of the distinct solutions of the equation ![]() is

is

![]()

Problem 21

The number of triples ![]() of positive integers which satisfy the simultaneous equations

of positive integers which satisfy the simultaneous equations

![]()

![]()

is

![]()

Problem 22

Let ![]() and

and ![]() be fixed positive numbers. For each real number

be fixed positive numbers. For each real number ![]() let

let ![]() be the vertex of the parabola

be the vertex of the parabola ![]() . If the set of the vertices

. If the set of the vertices ![]() for all real values of

for all real values of ![]() is graphed on the plane, the graph is

is graphed on the plane, the graph is

![]()

Problem 23

![]() equals

equals

![]()

Problem 24

If ![]() and

and ![]() are positive real numbers and each of the equations

are positive real numbers and each of the equations ![]() and

and ![]() has real roots, then the smallest possible value of

has real roots, then the smallest possible value of ![]() is

is

![]()

Problem 25

The total area of all the faces of a rectangular solid is ![]() , and the total length of all its edges is

, and the total length of all its edges is ![]() . Then the length in cm of any one of its interior diagonals is

. Then the length in cm of any one of its interior diagonals is

![]()

Problem 26

In the obtuse triangle ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() . If the area of

. If the area of ![]() is

is ![]() , then the area of

, then the area of ![]() is

is

![]()

Problem 27

In ![]() ,

, ![]() is on

is on ![]() and

and ![]() is on

is on ![]() . Also,

. Also, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . Find

. Find ![]() .

.

![]()

Problem 28

The number of distinct pairs of integers ![]() such that

such that ![]() and

and ![]() is

is

![]()

Problem 29

Find the largest value for ![]() for pairs of real numbers

for pairs of real numbers ![]() which satisfy

which satisfy ![]() .

.

![]()

Problem 30

For any complex number ![]() ,

, ![]() is defined to be the real number

is defined to be the real number ![]() . If

. If ![]() , then

, then

![]() equals

equals

![]()

See also

| 1984 AHSME (Problems • Answer Key • Resources) | ||

| Preceded by 1983 AHSME |

Followed by 1985 AHSME | |

| 1 • 2 • 3 • 4 • 5 • 6 • 7 • 8 • 9 • 10 • 11 • 12 • 13 • 14 • 15 • 16 • 17 • 18 • 19 • 20 • 21 • 22 • 23 • 24 • 25 • 26 • 27 • 28 • 29 • 30 | ||

| All AHSME Problems and Solutions | ||

The problems on this page are copyrighted by the Mathematical Association of America's American Mathematics Competitions.